My wife and I teach the 5-and-6-year-olds in our ward’s Primary, and we have distinct roles (I know “roles” is a loaded word on Mormon blogs, but bear with me). After we read the manual together, my wife prepares handouts, pictures, games/activities, and an outline for the lesson. My role is to become conflicted about the theme of the lesson during sacrament meeting, contemplate it during sharing time, and then confuse the children when we go to class by mingling my studies with everything my wife worked hard to prepare. I also hand out snacks.

Despite the kids’ confusion, I learn a lot in teaching Primary. One recent lesson—”I Have Talents”—sparked some thoughts I want to share. Since I study psychology, I’ll introduce a theory from psychological science and discuss how it relates to Mormon ideas of individual differences and self-improvement. But I won’t be giving out snacks, so don’t get your hopes up.

The lesson manual enlists Jesus’ parable of the talents to teach kids that God gives each person gifts that we should practice, improve, and showcase (most conspicuously: sports for boys, dance for girls, musical performance for all). Here’s a brief overview of the parable (Matthew 25:14-29): a boss man leaves town, trusting his servants with his assets—namely “talents.” A “talent” can be a coin, but more fundamentally is just a measure of weight. The boss gives ten, five, and one talent to three servants, respectively. The five and two talent guys use their master’s resources, and each one doubles what he was given. The one-talent servant buries his. The master returns and praises the two and five talent guys equally, telling them since they were faithful over some small potatoes, he’ll put them in charge of a lot more. The servant who hid his talent explains that he thought the master was unfair (after all, he gave very different amounts to the three servants) so he got scared and reckoned it was safer to hide the talent than risk losing it. Long story short, his boss is super unimpressed and the servant loses everything.

Besides the parable, the lesson manual includes two stories, one fictional and one just historically incomplete. The first story features Wendy, a little girl whose sister, Shelley, is a total all-star. Shelley dominates in piano, drawing, and book-smarts, while Wendy feels bad about her own apparent ineptitude. When Wendy has to give a talk in Primary, she spends time carefully preparing it and knocks the delivery out of the park. Her bishop sees the talk, compliments Wendy on it, and tells her she’s very talented. Touched by the Spirit, Wendy starts to recognize her unique talents and use them to bless others. It’s a heartwarming tale and could make a tear-jerker of a Mormon Messages video.

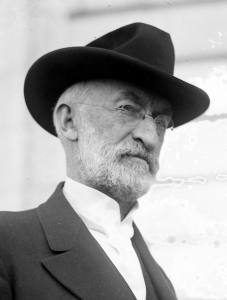

But the real star of the lesson’s talent show is former prophet and church president Heber J. Grant, champion of Mormon underdogs. The manual tells how young Heber just wasn’t very good at anything and his teachers and peers all thought he was going nowhere. But then he used his legendary persistence to practice and perfect his handwriting, ball skills, singing, etc. Heber’s hard work and stick-to-it-iveness led to utter mastery, as shown by his constant winning of awards.

Both of these inspiring stories are thoroughly Mormon and would be right at home in a general conference talk. But a tiny bit of scrutiny shows that they teach different, somewhat conflicting lessons. So which is it: are people stuck with whatever talents they have or don’t have, or can everyone become excellent at whatever they set their minds to?

The way I figure it out is to ask more questions:

- Do “talents” in the scripture story really just represent specific skills? What else could Jesus have meant?

- Is Heber J. Grant’s example a universal recipe for greatness? In other words, can the Wendys of the world take a page out of Heber’s book and rise to the same level of eminence? What are some alternative paths to success? (The fact that fictional Wendy was a girl and real Heber a boy is interesting and beyond the scope of this post).

Note: I’m not trained in scriptural exegesis and mine is not the one true interpretation of the parable of the talents. But the ideas I’ll share about these verses feel more grown up and useful than whatever I thought before, and might be helpful for some.

What did Jesus mean by “talents”?

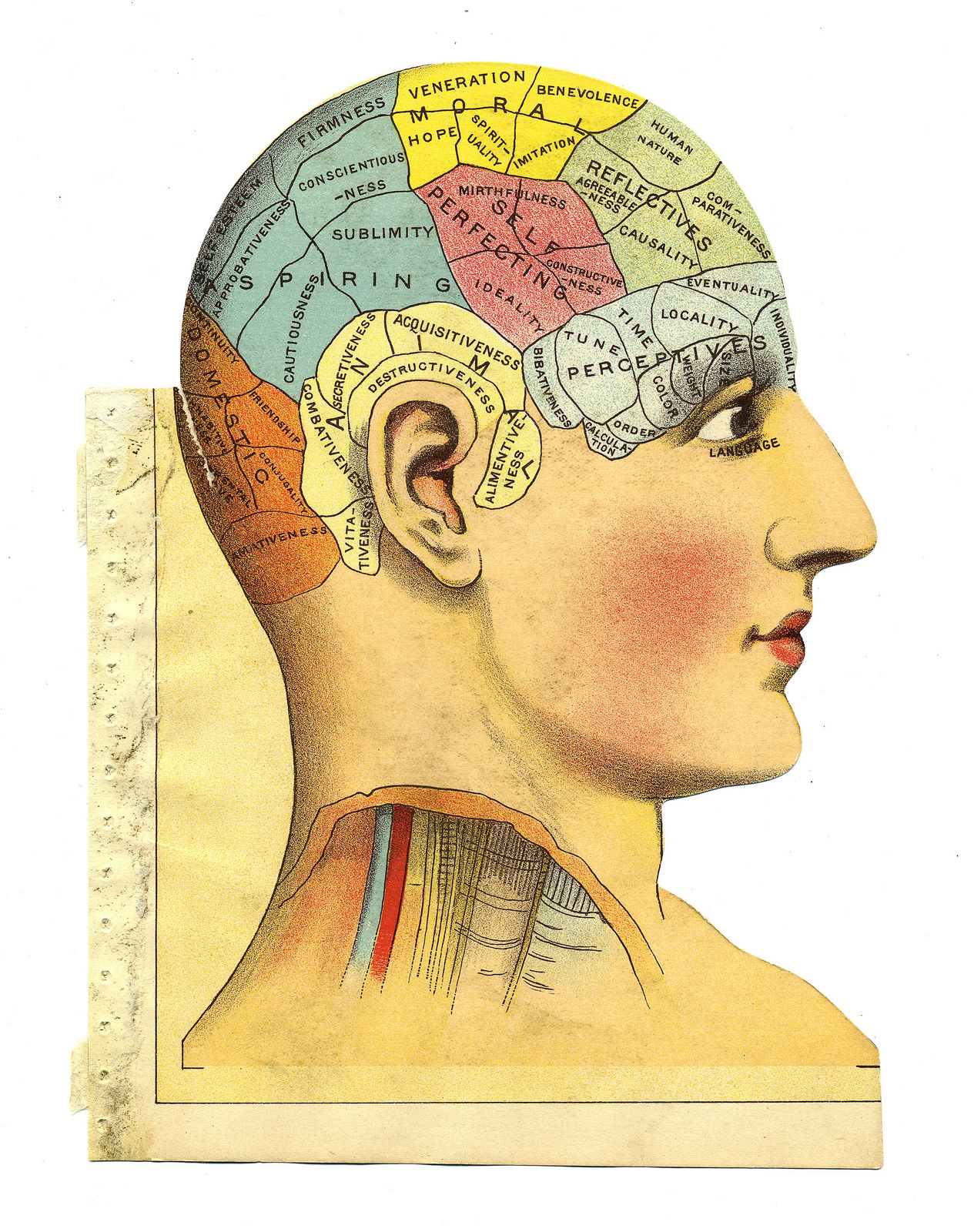

Traditionally, the talents in the scripture story are gifts—especially abilities or aptitudes—God gives us. It’s simplistic to regard only things like athletics (or mathletics) as talents, and the Primary manual does identify subtler talents like being kind or listening well. But what we almost never include are things like negative emotionality, shyness, rigidity, disorganization, or impatience. We see those things as liabilities and, like the fearful servant, we often hide them if we have them. For example: cheerfulness is a talent, but sadness is a trial to overcome. But what if each variation doesn’t equate to better or worse, and instead is just an observable difference in what God gives each person (remember the original meaning of “talent”)? That’s arguably the case in a scientific view of personality.

Scientifically, personality is a person’s unique and stable pattern of thinking, feeling, and behaving, and it starts to emerge early in life [1]. Some variation in personality is biologically determined before birth, and temperament—the precursor to personality—can be measured reliably in infants before they can talk [2]. Throughout early life, differences in brain structures develop along with personality and influence how we experience the world, make choices, and live our lives [3]. In other words, personality makes us unique and is largely outside of our direct control, which to me sounds similar to the talents from the parable. I’ll discuss one framework for understanding personality.

Converging evidence from years of research supports the Five Factor Model (FFM) as a framework for measuring and explaining individual personality differences (Digman, 1990). There are no “types” or color codes in FFM vernacular, just various configurations of all five factors (personality traits). Still, teaching Personality to undergrads has shown me that people distrust any hint of summarizing uniqueness (and apparently the movie Divergent has turned personality psychologists into villains). I’ll just say that personality assessment isn’t about fully explaining differences or deciding what anyone can or can’t do. The goal is to chart some key characteristics of a person relative to the rest of the population. We’ll see how this can be helpful later on.

Each of the factors in the FFM is measured on a continuum (e.g., emotional stability vs. volatility). I’ll summarize just three of the five factors to explore whether one side of each spectrum can be called better than the other.

Neuroticism. This trait represents a disposition toward “negative” internal experiences: sadness, anxiety, irritability, pessimism. High Neuroticism corresponds to experiencing more negative emotion and emotional reactivity. It seems obvious that lower Neuroticism is better, right? And yet, Neuroticism is the trait that makes a person watch out for harm or danger. High Neuroticism pays off crucially in many career and life contexts by facilitating appropriate responses to threat. The worry-wart mother may not be the life of the party, but she’s more likely to see a speeding car and move her child out of its way before it’s too late. Also, experiencing difficult emotions regularly can promote greater compassion for others’ pain.

Openness to Experience. I’ll own my bias and admit that I have a favorite trait. It’s Openness, which I see as especially important in contemporary Mormonism. Openness includes preference for new experiences; comfort with ambiguity; capacity for innovative mental connections; affinity for large and abstract concepts; appreciation of art, literature, nature, and other aesthetic experiences; and curiosity about one’s own emotions. People higher on Openness are typically more politically liberal, often show compassion for a wider variety of people, and are more likely to question authority (see Michael Barker’s recent post about moral foundations). Extremely high Openness can put a person too far outside the mainstream to form meaningful relationships, and can even be seen in schizophrenia or delusional disorders. Very low Openness can mean a person is inflexible, unrelenting, and closed-minded to a fault, rejecting opportunities because of unwillingness to consider new ideas or try new things. When we argue about things like “I know” testimonies or comfort with institutional change, Openness to Experience is a critical differentiator but not in itself a virtue (meaning it’s problematic to accuse others of being on the wrong side of Openness).

Conscientiousness. Probably Heber J. Grant’s favorite trait. The tagline for Conscientiousness is “effortful control.” Organization, industriousness, timeliness, neatness, and dependability are hallmarks of high Conscientiousness. That means the low end is related to sloppiness, lateness, procrastination, and so forth. But being on the low end can also mean a person is easy-going, not soon ruffled, and can go with the flow—which can be very adaptive in the right circumstance. Romantic partners, missionary companions, co-workers, and ward-council members with very high Conscientiousness may clash big-time if they have different views on how to be efficient, orderly, and productive.

Each of the five factors is normally distributed, meaning many people fall somewhere in the middle and few people are at the extremes of any trait. Most people have meaningful variation between the factors (like me: high-average N, low-average E, high O, average A, low C), which can help in figuring out what to do with your talents (pro-tip: don’t bury them).

But can I still be anything I want to when I grow up?

So couldn’t Wendy have read the Heber J. Grant story, been inspired, and practiced until she could wipe the floor with her sister? We sort of imply that when we tell Heber’s story: his secret for greatness was some internal thing that everyone has but only some decide to use. We emphasize Heber’s lack of natural ability because it strengthens the claim that any skill can be mastered by a simple choice to persist. Look closer, though, and it turns out that Heber J. Grant was inherently gifted: one of his talents was Conscientiousness, which includes persistence. It was part of his personality early, and we have the childhood stories to prove it. So perhaps Wendy was born with—and/or raised in an environment that resulted in—less capacity for bald persistence than Heber was given.

I suspect most people’s Conscientiousness is below Heber-level, and lots of people (e.g, me) want to change it. But personality remains pretty stable across the lifetime, changing gradually [4], and personality change rarely results from deliberate effort [5]. So although some people are motivated to action when they hear how Heber “made something of himself” through grit and willpower, others whose talent bundles include less grit are tempted to bury what they see as the mess they’ve been given.

Before anyone buries anything, consider that personality-envy might be a matter of the grass being greener in the other person’s soul. For example: we celebrate Heber for his wicked persistence, but we rarely mention his later health problems, which are revealing. Like many people who don’t temper their work ethic, President Grant suffered from chronic insomnia and other stress-related issues for much of his adult life [6]. At least in part, the ugly side of Conscientiousness seems to have caught up to Heber.

Does all of this mean I’m limited by the genes and environment I’ve been saddled with? If personality rarely changes drastically, and if what I have isn’t working for me, what’s left but to give up and call it hopeless? Before giving up, let’s look at what we can change.

Lord, is it I? Or is it my environment?

If you’ll never win the game no matter how much you practice, you find a way to change the game. This means changing your environment to complement your talents, and by environment I mean everything that isn’t you. People have more control now than ever over where to live and with whom, what to study, what to do for work, how to recreate, what to own, what to eat, and so on. Since altering one’s environment is increasingly doable, it’s ironic that people sink incredible effort into changing themselves—often in ways that are unrealistic and unhealthy. Each life is a product of what we start with (genes, some talents, spiritual gifts) multiplied by our environment’s effects on us, so why would we focus on changing the part of the equation that seems to be most fixed?

Conventional wisdom says if you are low in Conscientiousness, you can fix it by exerting willpower and trying repeatedly. That’s a frustrating trap, because willpower and persistence largely fall within Conscientiousness, something you already lack. You can’t use a resource you don’t have to get more of that resource. Fortunately, any resource you lack personally is probably available in the people and things you interact with. At a super basic level, this could mean something as simple as making your phone remember appointments because your brain isn’t very good at it.

More meaningful changes often require sharing personality resources within wards, families, and communities, which entails greater risk and reward. For any trait or disposition, probably someone has an excess and someone else in the vicinity who needs more. Someone high in Neuroticism might be accused of dragging the ship down with negative thinking or criticism, but that person is also likely to see things realistically and anticipate obstacles that should be addressed. Someone high in Conscientiousness runs the risk of being labeled a “Nazi” and getting on everyone’s nerves, but that person is also more likely to achieve timely, quality outcomes. The person high in Openness might be seen as just high—or at least unrealistically idealistic and unfocused. But that person can generate innovative suggestions, solve problems creatively, and keep sight of big-picture goals.

“Personality clash” is an easy copout to explain failures and justify blaming individuals, but it doesn’t have to be that way. People do clash because of personality differences, but each person is part of another person’s environment and could provide some crucial resource. I want a home-teaching companion whose low Openness can reign in my day-dreaming and make me schedule appointments. I want to use my high Openness to help the guy whose rigid view of church history and doctrine sparks a crisis when he reads some “Gospel Topics” essays. And since I don’t want to be blamed for the talents I’ve been given, I’ll try to avoid blaming others for theirs.

Endnote: If you’re really interested in a test that measures the five factors of the FFM, you can find a free online test at http://www.outofservice.com/bigfive/. Although it’s not my favorite, the test on that site has been shown to reliably measure the five factors. When you get your results, keep in mind that they only tell you how you compare to everyone else who has taken that test on that site. If you compared your answers to a group of only Mormons, for example, things might look quite a bit differently.

References

- Allport GW (1937) Personality: a psychological interpretation. Oxford England: Holt.

- Caspi A, Shiner RL (2007) Personality Development. doi:10.1002/9780470147658.chpsy0306.

- DeYoung CG (2010) Mapping personality traits onto brain systems: BIS, BAS, FFFS and beyond. Eur J Personal 24: 404–422.

- Costa PT, McCrae RR, Zonderman AB (1987) Environmental and dispositional influences on well-being: Longitudinal follow-up of an American national sample. Br J Psychol 78: 299–306. doi:10.1111/j.2044-8295.1987.tb02248.x.

- McCredie H (2013) What is personality change coaching and why is it important? A response to Martin, Oades & Caputi. Int Coach Psychol Rev 8: 99–100.

- Walker RW (2003) Qualities That Count: Heber J. Grant As Businessman, Missionary, and Apostle. Provo, Utah: Brigham Young Univ Pr. On page 277, Walker writes that “For years, [Grant] had pushed himself onward through the force of his strong will.” Brother Grant describes the adjustments he struggled to make for his health: “‘I try to eat slow and think slow and walk deliberately. These things are all new to my way of life.'”

This is why you were the HEART of the district!!! I really enjoyed it.