In this third part of my discussion of cosmic assumptions, I explain that not all infinities are created equal. I discuss different sizes of infinity, variation among universes, and assumptions we make about evidence. See the introductory post, here, and the follow up post, here.

- Assumptions about the Universe

- Universe or Multiverse?

- Finite or Infinite?

- Flat or Curved

- Finite numbers of forces and subatomic particles, or not

- Big and Small (and Infinite) Infinities

- Variation among universes

- Something between/surrounding universes, or not

- Assumptions about Evidence

- Only objective, only subjective, or a mix

- What mix is acceptable/admissible

- Assumptions about God

- Limited or unlimited knowledge, power, or presence

- What is the nature of the limitations

- Assumptions about God’s purposes

- Assumptions about the best ways to achieve those purposes

- One God or family of Gods

- Nature of God’s family

- Human interaction with God

- How involved is God, and how is God involved

- Limited or unlimited knowledge, power, or presence

- Conclusions: We all make assumptions, whether we identify them explicitly or not. Those assumptions bear on such important matters as our belief in God, how we react to new learning, how we feel about good and evil in the world, and how and where we devote our time and resources. For me, it’s worth taking the time to explore and evaluate those assumptions consciously, and you are invited to join me or observe my journey through this and subsequent blog posts.

Variation among universes

The questions I ended yesterday’s post with are ones we have to ask about every possible universe, if there is more than one. Are the numbers of universes infinite, or finite? Is there stuff between the universes, or does nothing exist except where there are universes? Are other universes finite or infinite? Do other universes obey the same laws and have the same subatomic particles as our universe? All of these are currently unanswerable questions, but the ways we think about God, religion, and any number of other things implicitly affirm certain subsets of assumptions and deny the possibility of others. Extrapolating back to our implicit assumptions can reveal inconsistencies in our beliefs. One of the most disconcerting is revealed when we think about there being no end to time and space in our universe–something many of us assume–and also accept the idea that there are multiple universes. Is it even possible for there to be two, infinite universes? If a universe is infinite, doesn’t it reach everywhere? And if it reaches everywhere, wouldn’t two, infinite universes overlap each other in time and space, and be one universe? The answer to these questions is no.

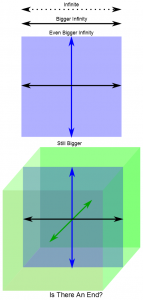

A line can be infinite and still be infinitely smaller than a plane. This heirarchy of infinities has no end, in theory. Whether it has a practical end in our cosmos is an open question.

Big and Small Infinities

Different sizes of infinities is not an idea that cosmologists or mathematicians struggle with, but the rest of us don’t always find it so natural. Infinities come in different sizes. They come in vastly different sizes. Imagine infinitely many libraries. How many books are in those libraries? How many pages? Letters? Ink molecules? Atoms? Getting the idea? But this doesn’t begin to show the scope. There are infinities so big that other infinities might as well be zero, when you put them next to each other. In the limit approaching infinity (you probably can’t really get there), some other infinities are zero. And there are potentially infinitely many sizes of infinity. Our Cosmos (that’s what I’ll call the sum of everything that is) might be made up of finities and infinities nested inside of each other, with some being so big that others vanish in insignificance, while others are so close in size that they have to share importance equally. The accompanying figure is intended to help you grasp this idea visually. First take an infinite series of points, sort of like counting by 1’s from negative infinity to positive infinity. That’s a lot of counting, but it doesn’t compare to the number of points in a continuous line spanning that same range. And a line is infinitely smaller than an infinite plane. Add a third dimension, and you are infinitely bigger. Is there an end? I don’t know. I think some really smart people would be surprised that their beliefs carry implicit assumptions about infinity that might not be true, or at least don’t support their religious (or anti-religious) conclusions. What do your beliefs imply about the infinities of the Cosmos? I’ll come back to that question in the future as we think about various understandings of Mormon Gods. Until then, maybe just try to get used to the idea that infinity comes in many sizes.

Evidence

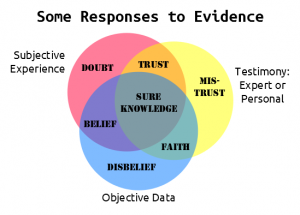

Nearly certain knowledge results when all our sources of evidence agree. When various sources disagree or are silent, we can have many different reactions. A few of the possibilities are shown in this figure.

One key factor influencing individuals’ beliefs is the nature of acceptable evidence. Most of us generally believe scientific data, with varying degrees of common sense scepticism. We are influenced by our expertise, our emotional investment in the subject, and our confidence in the practitioners or reporters of the science. Where we take issue is primarily in interpretation. Whether we can identify them or not, we are at least vaguely aware that scientific interpretation is influenced by human biases and methodological biases. For example, someone like me gives more weight to the professional opinions of LDS Egyptologists regarding the Book of Abraham than to Egyptologists who haven’t shown a deep (or even passable) understanding of Mormonism. It’s a bias I like. Another way we select our biases is in accepting or rejecting personal, subjective experience as credible evidence. Typically, people accept a level of subjective experience as evidence, but require checks and balances on its credibility. We require multiple witnesses in court. We require multiple labs to reproduce results on important findings. We require ourselves, as researchers, to replicate results multiple times in an attempt to reduce instrumental error and subjective, human error. Some psychological research must accept personal experience as real because that is the reality being studied. Where we divide is when scientifically objective reality and subjective personal experience conflict–or appear to.

I am not a cosmologist. I am not a climatologist. I am not an evolutionary biologist. I am a biophysicist, so I have many of the tools to understand and partially evaluate the explanations of these groups when their claims interest or influence me. So I make judgments about evolution, global warming, and the size and nature of the universe based on expert reports.

I am not a Prophet, Seer, and Revelator. I did not know Jesus or Joseph Smith personally. I am not a theologian, nor am I a historian of religion. I have received answers to prayers and had experiences where I believe truth was revealed to me. My grandparents’ grandparents knew Joseph Smith, personally. I’ve read a fair amount, including a modest amount of theology, philosophy, and history. In other words, I have some of the tools to evaluate the claims of professionals and prophets. I have my own witness, but I also trust my grandfather’s testimony who knew and trusted his grandfather, who personally knew and trusted Joseph Smith. It’s third hand trust, but it’s trust earned by lifetimes of demonstrated goodness, intelligence, and love. I trust these personal, subjective experiences. I claim them as evidence, for me. There are at least two other ways to treat these evidences: claim them as evidence for everyone, or reject them as evidence for anyone. Rejecting them for the purposes of scientific study does not require me to reject them as true, only as objective. What evidence do you accept? What checks and balances have you applied to it? These are questions I think you can’t ever stop asking if you aspire to eternal progression.

Unsettl(ed/ing) Science

Most of the assumptions I’ve identified so far are real, undecided questions in Science. Many of them will possibly never be decided, because pushing back the boundaries of the unknown will only reveal another level that leaves the same questions open–just in a different way. This can be unsettling and disconcerting enough that people react with strong emotion. Some doggedly assert that, even if there is reality beyond what we can observe, it is unethical to use that reality as grounds for deciding what we should do here and now. Others tell themselves, if scientists can’t even agree amongst themselves, I don’t need to pay any attention to them. I can just decide that my church, or my personal experiences are right without any reference to what has been measured scientifically. I hope most of us make an effort to find the most productive, middle ground to live in, even if it is harder or less certain.

Next Month

I’ll give those interested a little time for these ideas to settle. Next month I’ll pick up with assumptions we make about God and how God interacts with the observable universe, and I’ll try to connect the assumptions we make about the Cosmos to real, everyday ethical choices that confront us.

I wish I could think of an engaging way to respond to this. Mostly I just find it really interesting and like that what you write makes me stretch my brain power to keep up with you… which I barely do. And I mean that in a good way.

I expect I’ll start getting more comments when I start making claims about what different views of the cosmos tell us about God–and what Mormon views of God tell us about the cosmos. Then I will have people all over my case, despite my not claiming to prove anything. Just give me a couple of months. These posts are two parts fun and one part laying the groundwork to defend myself in the future.

Ditto. This series is so great! Keep it up – especially because you keep sprinkling “but we’ll talk about that in future posts” all over the place 🙂

This is really old, but I just saw this and as a math nut, I feel the need to point out that while there are absolutely different sizes of infinity (infinitely many different sizes, even, although telling whether there are more than countably many is tricky), a line is not actually a smaller infinity than a plane. See http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cardinality for a better explanation than I can give 🙂 love this series, by the way 🙂

This is really old, but I just saw this and as a math nut, I feel the need to point out that while there are absolutely different sizes of infinity (infinitely many different sizes, even, although telling whether there are more than countably many is tricky), a line is not actually a smaller infinity than a plane. See http://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cardinality for a better explanation than I can give 🙂 love this series, by the way 🙂

Thank you, Marissa. If you can help me formulate a more accurate and easy to present picture, I would appreciate it. I mostly get the basic idea, that there are different sizes of infinity, and even get the gist of mapping and countability, but definitely don't get the details enough to communicate it accurately. My dad had a similar reaction to yours, but kind of let it go as "close enough".

It probably is ‘close enough’, especially since you could get into an argument about measure (length) vs cardinality (# of things). For cardinality, the main idea is that of a power set, i.e. the set of all subsets (so for the integers, it would be the set of all sets of integers), which has to have greater cardinality (proof here: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Cantor%27s_theorem, but hopefully it’s intuitive enough for finite sets that it makes sense that it would be true for infinite sets), and then no matter how big of a set you have, you can always, always construct a bigger one by taking its power set.

You could also emphasize the dimension idea instead of ‘big and small infinities’; imagine how much more freedom you have to move around and space you have to work with going from one dimension to two dimensions to three, and what would happen if you didn’t have to stop there. Another interesting thought is that even if the universe is unbounded, that doesn’t mean it’s infinite; our Earth is finite, but you can travel all over its surface without falling off since it’s not flat. Our universe could be the three-dimensional analogue of the surface of a sphere. ‘The Poincare Conjecture: In Search of the Shape of the Universe’ is a really good read and talks about that.

I don’t think I’m actually really complaining about your original post or insinuating that you should change it, this is just really fun stuff to think about. LOVED ‘Love Conquers the Multiverse’, by the way.

Good suggestions. Next rewrite I’ll keep them in mind. And I’m glad you liked the ‘Love’ post. I worry that it’s narcissistic, but I really love the story that post tells. It makes me happy. The next one’s even better, for me, but partly because it’s an unfinished story and I only think I know where it will end.

Also, cardinality is probably better than measure, since space is very possibly composed of relationships between quantized particles, and thus quantized (and emergent) itself. But the numbers and types of relationships are best described as additional dimensions. A network type picture is probably the best image for that.