Podcast: Play in new window | Download

Subscribe: Apple Podcasts | RSS

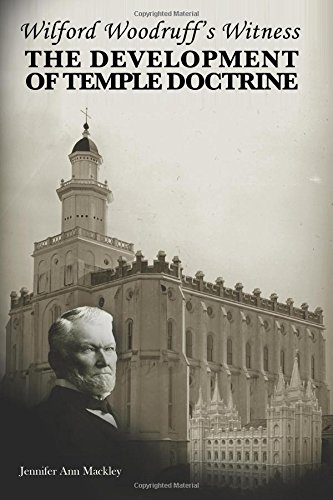

Wilford Woodruff’s Witness: The Development of Temple Doctrine recounts Wilford’s life and his account/view of the development of the Temple using as frequently as possible his own words. Looking at Woodruff, the temple, and church policy/development as an interdependent triad is insightful and can even be paradigm shifting. The author Jennifer Mackley is very knowledgeable of Woodruff’s life and writes the book from Woodruff’s point of view, thus making a history book that is more faith-friendly than Rough Stone Rolling.

It was very interesting to learn how involved Wilford Woodruff was in the development of Temple theology and rites even while Brigham Young and John Taylor were presidents of the church. I wished more details of the book had been shared, but it effectively made me want to read more.

Jennifer,

I have a few questions for you.

Can you give me the historical context of OD #1. I’v heard things such as, what is the relationship between the Manifesto and OD #1? Somehting about a Cache Valley Stake Conference in Logan and President Woodruff making the Manifesto a “revelation”; etc. Just hoping if you could contextualize it for me. Dr. Kathleen Flake adn Sarah Barringer Gordon talk about it, but don’t really address the questions I have.

Second: I am wondering if you would be interested in coming on for a second podcast. It would cover the anti-polygamy legislation – the Morrill Act of 1862; the Poland Act of 1874; the Edmund Act of 1882;the Edmund Tucker Act of 1887; the Polk Act; etc. What were these acts exactly? How did they affect the Church and the Church laity? How do you enforce an “unlawful cohabitation” law? the case of Late Corporation of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints vs. United States which upheld the Edmunds Tucker Act; etc.

– mike

Mike,

You asked about the historical context of Official Declaration #1, which was first printed in the 1908 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants, and its relationship to the Manifesto issued by Wilford Woodruff on September 25, 1890. Your comment that Wilford Woodruff subsequently “made it a revelation” implies that he didn’t think the Manifesto was inspired at the time it was issued, or at least did not present it as such. Of course, many details are not included below, but I tried to at least incorporate all the known references to Wilford Woodruff’s inspiration beginning on September 24, 1890. You also ask about the anti-polygamy legislation that preceded the Manifesto. I am not an expert on the details of the legislation, but it is part of the contextual history of the Manifesto so I hope the following helps shed some light on both. I am happy to dig deeper if the following does not shed enough light!

Joseph Smith’s “Revelation on the Eternity of the Marriage Covenant, Including the Plurality of Wives” was written down July 12, 1843, although the practice had been introduced earlier. The first official acknowledgment of plural marriage was made by Orson Pratt on August 29, 1852. His task was to prove plural marriage was “incorporated as a part of our religion, and necessary for our exaltation to the fullness of the Lord’s glory in the eternal world.” He reasoned that “the constitution gives the privilege to all the inhabitants of this country, of the free exercise of their religious notions, and the freedom of their faith, and the practice of it.” If the Saints had embraced plural marriage “as a part and portion of their religion,” then it should therefore be constitutional. “And,” he concluded, “should there ever be laws enacted by this government to restrict them from the free exercise of this part of their religion, such laws must be unconstitutional.”

The Morrill Anti-Bigamy Act was the first law passed by Congress. Although the Morrill Act was signed into law by President Abraham Lincoln on July 8, 1862, he did not provide funds or the manpower to enforce it. Another twelve years would pass before the Poland Act provided a basis for the prosecution of polygamists. George Reynolds’ indictment under the Morrill Act in October 1874 was upheld by the Supreme Court. In applying the First Amendment, the Court concluded that, “Congress was deprived of all legislative power over mere opinion, but was left free to reach actions which were in violation of social duties or subversive of good order.”

A third law, The Poland Act, was passed on July 23, 1874 and redefined the jurisdiction of Utah courts. It gave the federal courts authority over all civil and criminal cases in the Territory of Utah and banned anyone practicing polygamy from jury service. The Edmunds Anti-Polygamy Act of 1882 not only reinforced the earlier legislation, but revoked the voting rights of all polygamists and prohibited them from holding political office. The Edmunds Act went a step further because restrictions were enforced regardless of whether an individual was actually practicing polygamy. A person could be indicted for just believing in the doctrine of plural marriage without actually participating in it.

Wilford Woodruff did not think the Supreme Court’s interpretation was what the Founding Fathers had in mind when they drafted the Constitution. “If it was only intended that men should think and not act, why not say so in the instrument? Why should it be stated that ‘Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof,’ if men were not to be allowed to act?”

In order to remove the requirement of proving a marriage had actually occurred, “unlawful cohabitation” was also prohibited under the Edmunds Act. As a result, on March 25, 1882, President John Taylor and his counselors agreed to advise all men to live with only one wife under the same roof. Prosecution under the Act began in earnest in 1884 under Judge Charles Zane and eventually over 1,300 were jailed; men for violating the law and women for contempt of court for refusing to testify. The Idaho Test Oath of 1884 disenfranchised anyone who practiced polygamy or was a member of “any order, organization or association which teaches, advises, counsels, or encourages its members, devotees, or any other person to commit the crime of bigamy or polygamy … as a duty arising or resulting from membership in such order,” effectively prohibiting all Church members from voting.

Because Church leaders were in hiding and unable to address the Saints publicly in General Conference, the First Presidency issued an Epistle on October 6, 1885. They stated, in part, “We did not reveal celestial marriage. We cannot withdraw it or renounce it. God revealed it and He promised to maintain it, and to bless those who obey it.” Pointing out the unjust punishment, for their beliefs rather than their actions, of the 9 out of 10 Mormons who did not practice polygamy, the First Presidency questioned the absurd application of flagrantly unconstitutional laws. Mormon colonies were established in Mexico in 1885 and in Canada in 1887 so those practicing polygamy could live without fear of arrest.

Finally, the Edmunds-Tucker Act was passed on March 3, 1887. This Act disincorporated the Church and the Perpetual Emigration Fund and allowed the escheatment of all Church property over $50,000. The right of women to vote in Utah was revoked and the education system was put under federal control. The spousal privilege was rescinded in Utah courts, which meant wives could be forced to testify against their husbands. In June 1887, President John Taylor approved a proposed Utah Constitution which prohibited bigamy and polygamy, and Utah voters approved it in August. Nevertheless, Congress rejected the proposed Constitution and denied Utah’s seventh petition for statehood.

Although Church leaders stopped publicly advocating for plural marriage, the restrictions remained as the fight over the Edmunds-Tucker Act was appealed to the Supreme Court. On October 17, 1887, Receiver Frank Dyer took possession of the President’s Office, the Temple Block in Salt Lake City, the Tithing Office, the Gardo House, and the Church Historian’s Office. By agreement, the St. George, Manti and Logan temples were exempted from confiscation because they were “occupied exclusively for purposes of the worship of God.” (Through a court ruling on October 8, 1889, the Temple Block was returned to the Church.)

As previous Church presidents had done, Wilford Woodruff prayed for guidance on whether they should continue the practice of polygamy. On November 24, 1889, the answer to Wilford Woodruff was, “Let not my servants … deny my word or my law … Place not yourselves in jeopardy to your enemies by promise … I, the Lord will deliver my Saints from the dominion of the wicked, in mine own due time and way. I cannot deny my word, neither in blessings nor judgments.”

By early December 1889, the Utah Territorial Supreme Court issued a decision sustaining the escheatment of church property. Early in 1890 quiet restrictions on the performance of plural marriage had been put into place. For example, on April 10, 1890, Wilford Woodruff said no more plural marriages would be performed in Mexico unless at least the plural wife remained in Mexico.

After the U.S. Supreme Court ruled the Idaho Test Oath was constitutional in February 1890, the Cullom-Struble Bill was introduced in Congress in April. This bill threatened to disenfranchise all members of the Church in all territories of the United States. The Bill stated, in part, that no person who was a member of, or supported any organization which taught any person to “enter into bigamy, polygamy, or such patriarchal or plural marriage” would be allowed to vote, serve on a jury, or hold any civil office. Had the Cullom-Struble Bill passed, it would have applied to all members of the Church whether or not they practiced plural marriage. In addition, it would have applied to all persons who supported or contributed to the Church in any way, whether or not they were members.

Then on May 19, 1890, in a 5-4 decision, the Supreme Court ruled that the Edmunds-Tucker Act was Constitutional and the federal government therefore had the right to confiscate the Church’s property. That summer a special commissioner was appointed to review Frank Dyer’s actions in regard to the confiscated Church property. Among other things, Dyer was criticized for allowing the 1888 agreement which exempted the temples from government seizure. The purpose of the hearings was to determine if the Utah Territorial Supreme Court’s acceptance of the agreement had been wrong. If so, then the new receiver could begin actions to take the temples and other formerly exempt properties. On August 16, 1890, with the Territorial Court’s decision looming, Wilford’s declared, “We must do something to save our Temples.”

The court issued a subpoena on September 2, 1890, for Wilford Woodruff to testify on the escheatment case regarding the temples. After the First Presidency met with the Church’s lawyers, they left for San Francisco on September 3 to avoid testifying in the upcoming proceedings. While in California they met with some of the political advisors that had previously advocated with the government on their behalf. The straightforward advice Wilford received was already obvious: the government would not restore the Saints’ civil rights and their ability to self-govern as long as they continued to practice polygamy.

On September 14, 1890, the Salt Lake Tribune printed the report of the federally-appointed Utah Commission. (The Utah Commission had submitted their annual report to the Secretary of the Interior on August 22. It stated that 41 new plural marriages had been solemnized since their 1889 report.) The First Presidency returned to Salt Lake City on September 21, facing the new accusations and the same dilemma. A telegram from the Church’s representatives in Washington, D.C. informed them that the Utah Commission’s report would be used to justify passage of additional legislation such as the proposed Cullom-Struble Bill.

The First Presidency again met with the Church’s attorney and other advisors on September 22, 1890. Then Wilford called a meeting of the Apostles for September 24. In preparation for the meeting, Wilford spent that night in prayer. He received an answer and recorded in his journal that he was “prepared to act.” On September 24, he presented his version of the Manifesto to his counselors and three Apostles and explained it was what the Lord wanted them to do to save the temples and continue temple ordinance work. Among those present at the meeting who heard Wilford explain why he decided to issue the Manifesto was Apostle Marriner W. Merrill, President of the Logan Temple. Following their discussion, Marriner recorded in his journal that he agreed with Wilford’s decision. He also believed the Manifesto was “the only way to retain the possession of our Temples and continue the ordinance work for the living and dead, which was considered more important than continuing the practice of plural marriage for the present.”

The same day Franklin D. Richards recorded that they met and “considered the text of President Woodruff’s manifesto critically and the same was unanimously agreed on by all present ….” The Apostles spent hours discussing the wording of the Manifesto so they did not say too much or too little. The next day Lorenzo Snow, President of the Quorum of the Twelve, read and approved the Manifesto. Finalized in the form of a press release and signed only by Wilford Woodruff, it was published in newspapers across the country.

Over the next few days, the Apostles continued their discussions. On September 30, 1890, the Quorum of the Twelve met to discuss how the Manifesto was being received both within the Church and by the country at large. Their acceptance of this temporary suspension of plural marriage was unanimous. Heber J. Grant’s journal gives detailed insight into each Apostle’s reaction. Lorenzo Snow “approved the Manifesto fully . . . [and] was sure good would result from [its] publication.” He noted that, “He had not given up plural marriage and we should not and could not do so. But . . . in the providence of God we were for the present relieved . . . from the entering into that relation.” Franklin D. Richards said, “Those among the people who had the spirit of revelation would approve of the Manifesto . . . and that he was convinced that God was with President Woodruff when he was preparing the Manifesto for publication.” John W. Taylor said, “I know that the Lord has given this Manifesto to President Woodruff and He can take it away when the time comes or He can give it again. I feel all right now and am glad that I do.” Moses Thatcher felt “The Manifesto had come by the inspiration of the Spirit to President Woodruff and that it was all right with him.” Francis M. Lyman said that he had endorsed the Manifesto fully when he first heard it.

On October 1, 1890, the Apostles met again and heard from John Henry Smith, Heber J. Grant, John W. Taylor and Anthon H. Lund. John Henry Smith was disturbed by the Manifesto but he was willing to sustain President Woodruff in issuing it. In contrast, Heber J. Grant felt “Easy and happy over the Manifesto and felt that it was the right thing at the right time and that there was not the least reason why such a document should not be issued as we had already come to the decision that we as leaders of the people should not allow any more persons to be married in the United States, and that in case a person wished a second or third wife he must go out of the United States and get her and that after he was married he should not bring her in to this country.”

Anthon H. Lund, who was not present at the September 24th meeting, felt “all right” about the Manifesto because President Cannon had explained to him “the way in which the matter had impressed [the] mind of our President.” Abraham H. Cannon said that the Manifesto “had not in the least disturbed him, as he had recognized in the publication simply the announcement to the world of what we were already doing. He felt that the Lord had suggested to President Woodruff to publish the Manifest and that was sufficient for him. The faithful saints would sustain the Manifesto. Felt the Lord would not ask us to do that which would not be in our best good.”

The Manifesto was formally approved and sustained by the First Presidency and the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles on October 2, 1890. But the government officials demanded more than just a declaration by the President and highest governing body of the Church. They asked for a public acceptance of the Manifesto by the general Church membership. Therefore, on October 6, ten days after the press release, the Manifesto was read in General Conference. Lorenzo Snow then called for a vote to accept as authoritative and binding President Woodruff’s declaration concerning plural marriages. “I move that, recognizing Wilford Woodruff as the President of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, and the only man on the earth at the present time who holds the keys of the sealing ordinances, we consider him fully authorized, by virtue of his position, to issue the Manifesto which has been read in our hearing, and which is dated September 25, 1890, and that as a Church in General Conference assembled, we accept his declaration concerning plural marriages as authoritative and binding.” Some of those present abstained from voting, but the remainder sustained their prophet’s decision and the vote in favor was considered unanimous.

George Q. Cannon then testified that the Manifesto was from God and was supported by the Apostles. He added that at no time before then had the Spirit “seemed to indicate that this should be done. We have waited for the Lord to move in the matter; and on the 24th of September, President Woodruff made up his mind that he would write something, and he had the spirit of it. He prayed about it and besought God repeatedly to show him what to do. At that time the Spirit came upon him and the document that has been read in your hearing was the result. I know that it was right…. he did this with the approval of all of us to whom the matter was submitted, after he made up his mind, and we sustained it; for we had made it a subject of prayer also, that God would direct us.” Knowing there were those whose faith had been challenged by the announcement, he asked them to do as their leaders had done, and pray for their own confirmation that this was God’s will.

Wilford Woodruff closed the Conference by restating his conviction: “I want to say to all Israel that the step which I have taken in issuing this manifesto has not been done without earnest prayer before the Lord. I am about to go into the spirit world, like other men of my age. I expect to meet the face of my heavenly Father . . . and for me to have taken a stand in anything which is not pleasing in the sight of God, or before the heavens, I would rather have gone out and been shot. . . . I am not ignorant of the feelings that have been engendered through the course I have pursued. But I have done my duty, and the nation of which we form a part must be responsible for that which has been done in relation to this principle.”

For the next few years Wilford found it necessary to defend and explain his decision to issue the Manifesto. This was in part due to the fact that Wilford, like his predecessor John Taylor, had stated emphatically and repeatedly for decades that the Church would not renounce polygamy. The same reasons Wilford had given earlier for not suspending or stopping the practice and for not renouncing or denying the principle of plural marriage, were now being thrown back at him. He faced and endured the inevitable accusations from within the Church that he had lost the Spirit, betrayed those who had stood their ground for so many years, even apostatized.

Wilford’s response to the various accusations came from the very revelation he received on November 24, 1889, leading to the Apostles’ refusal to suspend polygamy a year earlier. On that occasion the Lord had promised, “If the Saints will hearken unto my voice, and the counsel of my servants, the wicked shall not prevail. . . . I the Lord will deliver my Saints from the dominion of the wicked, in mine own due time and way.” It was not up to the dissenters within the Church, the persecutors outside the Church, the monogamist majority of Church membership, John Taylor, or Wilford Woodruff. “We did not reveal it,” Wilford said, “—we cannot denounce or withdraw it.”

Wilford testified that the Lord’s approach was different than his own, that 1890 was the time, and that the Manifesto was the way that God had chosen to deliver them from their enemies who sought not the end of polygamy, but the destruction of the kingdom of God. If he had to choose between pleasing God or man, he said would choose to do what God instructed.

Even Charles S. Varian, the attorney representing the United States government, understood that the change in Church policy stated in the Manifesto was not because Church members decided to obey man’s laws rather than the laws of God. He recognized that the Saints’ decision was grounded in their belief that, as prophet, Wilford Woodruff spoke God’s will. Furthermore, “though the practice of polygamy had ceased, the principle was undying.”

According to court testimony from October 28, 1891, Varian stated, “They are not obeying the laws of the land at all . . . but the counsel of the head of the church. The law of the land, with all its mighty power, and all the terrible pressure it was enabled to bring with its iron heel upon this people, crushing them to powder, was unable to bring about what this man did in an hour in the assembled Conference of this people. They were willing to go to prison; I doubt not some of them were willing to go to the gallows, to the tomb of the martyr, before they would have yielded one single iota.”

Each time Wilford spoke of the process he went through to arrive at this pivotal moment in Church history, his explanation was the same: God directed him to suspend the practice of plural marriage to save the temples and the priesthood, and thus continue the saving work for the living and dead. On November 1, 1891, Wilford Woodruff spoke at the Cache Stake Conference in Logan. Referring to the Manifesto, he said,

“The Lord has told me to ask the Latter-day Saints a question . . . The question is this: Which is the wisest course for the Latter-day Saints to pursue—to continue to attempt to practice plural marriage, with the laws of the nation against it and the opposition of sixty millions of people, and at the cost of the confiscation and loss of all the Temples, and the stopping of all the ordinances therein, both for the living and the dead, and the imprisonment of the First Presidency and Twelve and the heads of families in the Church, and the confiscation of personal property of the people (all of which of themselves would stop the practice); or, after doing and suffering what we have through our adherence to this principle to cease the practice and submit to the law, and through doing so leave the Prophets, Apostles and fathers at home, so that they can instruct the people and attend to the duties of the Church, and also leave the Temples in the hands of the Saints, so that they can attend to the ordinances of the Gospel, both for the living and the dead?

“The Lord showed me by vision and revelation exactly what would take place if we did not stop this practice. If we had not stopped it, you would have had no use for … any of the men in this temple at Logan; for all ordinances would be stopped throughout the land of Zion. Confusion would reign throughout Israel, and many men would be made prisoners. This trouble would have come upon the whole Church, and we should have been compelled to stop the practice. Now, the question is, whether it should be stopped in this manner, or in the way the Lord has manifested to us, and leave our Prophets and Apostles and fathers free men, and the temples in the hands of the people, so that the dead may be redeemed. A large number has already been delivered from the prison house in the spirit world by this people, and shall the work go on or stop? This is the question I lay before the Latter-day Saints. You have to judge for yourselves. I want you to answer it for yourselves. I shall not answer it; but I say to you that that is exactly the condition we as a people would have been in had we not taken the course we have. . . . I saw exactly what would come to pass if there was not something done. I have had this spirit upon me for a long time. But I want to say this: I should have let all the temples go out of our hands; I should have gone to prison myself, and let every other man go there, had not the God of heaven commanded me to do what I did do; and when the hour came that I was commanded to do that, it was all clear to me. I went before the Lord, and I wrote what the Lord told me to write.”

Wilford Woodruff had previously gone to God in prayer many times regarding plural marriage. However, in the fall of 1890, Wilford’s query was different. His prayer was for the temples and the work that could only be carried on in places dedicated for that purpose. God’s response was also different. God showed Wilford a vision, not of the apocalyptic end to the United States government he had expected, but of the end of all ordinances on both sides of the veil. Wilford said he did not know why the Manifesto was the answer, but he trusted that God knew.

Wilford believed that God had commanded Joseph Smith to begin the practice and that God directed Wilford to suspend it. The principle was not changed by the Manifesto. The Manifesto did not revoke the law of plural marriage or deny its revealed origins. In fact, in their discussions regarding issuance of the Manifesto, the Apostles had specifically agreed only to temporarily suspend the practice. And Wilford firmly believed that the situation would only last for a short time . . . until Christ would come and they would not be subject to the laws of men, but of God.

But Christ did not come as quickly as they hoped and the financial and physical state of the Church remained precarious. The Manifesto was resustained in the October 1891 General Conference and the understanding of its interpretation and application was expanded. Initially it was understood that the Manifesto only applied to future plural marriages, and only marriages within the United States. From the time the Manifesto was published in September until November 1890, seven couples traveled from the United States to Mexico to be married there. (All but one of the couples remained in the Mexican colonies, and it was the problems caused by the one that returned that led to Wilford Woodruff’s cessation of the practice.) After approximately six months during which no new plural marriages were performed anywhere, four marriages were performed in 1891 for residents of the Mormon colonies in Mexico.

However, a year after the Manifesto, the escheated Church property and funds had not been returned because the government wanted further clarification on cohabitation with plural wives and the application of the Manifesto to all plural marriages no matter where they were performed. In testimony before the Master of Chancery on October 19-20, 1891, the First Presidency reaffirmed that the Manifesto was the result of God’s inspiration to Wilford Woodruff. When asked if the Manifesto included living with plural wives, Wilford Woodruff answered, “Yes, sir; I intended the proclamation to cover the ground, to keep the laws – to obey the law myself, and expected the people to obey the law.” Later, for clarification, he was asked if that meant, “That there should be no association with plural wives; in other words, that unlawful cohabitation as it is named, and spoken of, should also stop, as well, as future polygamous marriages,” he again answered “Yes.” When asked if the Manifesto applied to the Church everywhere, in every nation and every country, he said “Yes.”

The following day, October 21, Wilford Woodruff stated that the Manifesto “was just as authoritative and binding as though it had been given in the form of ‘thus saith the Lord’ and that its affecting unlawful cohabitation cases was but the logical sequence of its scope and intent regarding polygamous marriages, as the laws of the land forbid both, and that therefore, although he at the time did not perceive the far-reaching effect it would have, no other ground could be taken than that which he had taken and be consistent with the position the manifesto had placed us in.”

The assumption that additional plural marriages would be solemnized after the Manifesto, and many husbands and fathers would maintain their polygamous family relationships, was echoed by those in and out of the Church. It took decades and the passing of a generation to change family dynamics, economics, and circumstances. The fact that they had made eternal covenants to each other was both a comfort and complication. It took many councils and courts to address the issues that arose from the Manifesto. In the meantime, federal persecution continued. The final anti-polygamy legislation was included in the Immigration Act of 1891, which denied polygamists admission into the United States.

On December 19, 1891, Church leaders formally petitioned the President of the United States for amnesty. The petition stated: “We formerly taught our people that polygamy, or celestial marriage, as commanded by God through Joseph Smith, was right; that it was necessary to a man’s highest exaltation in the life to come. The doctrine was publicly promulgated by our president, the late Brigham Young, forty years ago, and was steadily taught and impressed upon the Latter-day Saints up to a short time before September 1890. Our people are devout and sincere, and they have accepted the doctrine, and many embraced and practiced polygamy . . . . In September, 1890 the present head of the church in anguish and prayer cried to God for help for his flock and received the permission to advise the members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints that the law commanding polygamy was henceforth suspended . . . . At a great semi-annual conference, which was held a few days later, this was submitted to the people . . . and was by them in the most solemn manner accepted as the future rule of their lives. They have been faithful to the covenant made that day . . . . We ask amnesty for them and pledge our faith and honor for their future.” The First Presidency and ten Apostles signed the petition. President Benjamin Harrison—who had met Wilford, visited Utah in 1891, and asked Church leaders to pray for his wife when she was seriously ill in 1892—granted a limited amnesty in January 1893 to those who had ceased practicing plural marriage when the Manifesto was issued. But Wilford believed it was of “little benefit” because it only applied to those who had been in compliance with the law since the Manifesto was issued.

Three months later, in April 1893, as they celebrated the end of their forty-year struggle to build the temple in Salt Lake City, Wilford testified that God had overcome Satan’s designs to destroy the work and prevent the Saints from completing the magnificent temple. During the fourth session of the dedication services, Wilford Woodruff referred to his experiences that precipitated the 1890 Manifesto. He reminded them, “Yes, I saw by vision and revelation this Temple in the hands of the wicked. I saw our city in the hands of the wicked. I saw every temple in these valleys in the hands of the wicked. I saw great destruction among the people. All these things would have come to pass, as God Almighty lives, had not the Manifesto been given. Therefore, the Son of God felt disposed to have that thing presented to the Church and to the world for purposes in his own mind.” Wilford then testified that the purpose God had in mind was the salvation of His children on both sides of the veil: “The Lord decreed the establishment of Zion. He had decreed the finishing of this temple. He had decreed that the salvation of the living and the dead should be given in these valleys of the mountains.”

Six months later, on October 25, 1893, Congress finally authorized the return of Church properties. The following year, on July 17, 1894, President Cleveland signed the Utah Enabling Act that would allow Utah to finally be admitted into the Union as a state. Wilford’s journal entry reflects his relief, “This has been a hard struggle for years as it has seemed as though all earth and Hell had been combined against the Latter-day Saints having a state government. And now we have to give God the glory for our admission into the Union.”

Perfect. I had a hard time, after reading Kathleen Flake’s and Sarah Barringer Gordon’s books putting everything in a clear chronological order.

What you have written here would make a great blog post. May we do that? I think maybe publishing this as a post in conjunction with a podcast with you would be amazing.

– Mike

Absolutely. Thanks Mike.