This is the 3rd post in my series on the Milgram experiments. See Parts One and Two

In my first post I discussed what we can learn from the Milgram experiments about obedience and authority, specifically about how authority can affect our moral decision making. In the second post I discussed what we can learn from the Milgram experiments about how our proximity to those whom we hurt (or whom are hurting in general) affects our willingness to stop the harm. This is the final post in my Milgram series. I’m going to again briefly summarize the experiment again, focusing on a few of the dozens of variations of the experiment.

The “Experimenter” is the person running the experiment and giving commands to the “Teacher.” The “Teacher” is the actual subject of the study. The Teacher gives shocks of increasingly higher voltages to the “Learner” every time the Learner answers a question incorrectly. The Experimenter tells the Teacher when to do this. The Learner in the main experiment was in a different room and the Teacher could hear the screams of pain as the shocks reached higher and higher voltages. There were 20-40 different variants of this experiment. When Milgram set out to do this experiment, he assumed that maybe 1% of the subjects would shock the Learner to the point of unconsciousness, or death. In the baseline experiment (the famous one), 65% of people obey all the way to the point of the Learner’s unconsciousness/death.

Now, as one might assume, the subjects (Teachers) during these experiments often had debates with themselves and debates with the Experimenter. Upon hearing the pain they were causing in the Learner they questioned the morality of continuing. They would tell the Experimenter (Authority figure) that they needed to stop. So how was the Experimenter to respond? This was a standardized experiment, so there had to be standard responses given by the Experimenter. All responses would be to prod the subjects to continue shocking at higher and higher voltages. The ‘prods,’ or specific text used, are another very interesting aspect to the study.

There were four prods:

1: “Please go on.”

if they didn’t, then

2: “The experiment requires that you continue.”

if still resisting…

3: “It is absolutely essential that you continue”

and the last is an absolute order:

4: “You have no other choice”

And what would the Experimenter say if the person continued protesting while still feeling the need to comply with the Experimenter?

As it turns out, that didn’t matter. Every single time the 4th prod was used, the subject absolutely disobeyed and asserted that they did in fact have a choice and they would not continue.

For me, this is the most fascinating aspect of the experiment and it really casts the entire experiment in a new light for me. So as long as the Experimenter is able to ask kindly or press the importance of the situation, they could get the subject to do horrible harm to others. However, every time they told the subject that they had no choice, the person refused. It seems as though there is a psychological line that is crossed when you tell someone that they have no choice. It is possible to get them to do all manner of horrible things if you (as an authority figure) imply the necessity of those things, but apparently you must be careful to not say that they have no other choice. The act of telling someone that they have no choice seems to make the person recall that they do have the choice to disagree with and disobey the authority. Mormonism of course places a great deal of importance on personal agency. The idea that someone would be denied the ability to choose was enough to justify a war in heaven.

To really dig into what role authority played in the decision making of the individuals in the Milgram experiments, I want to briefly mention here Jonathan Haidt’s 6 moral systems. He argues that there are these 6 aspects of morality:

Care/Harm

Liberty/Oppression

Fairness/Cheating

Loyalty/Betrayal

Authority/Subversion

Sanctity/Degradation

How we prioritize these aspects of morality can make a drastic difference in our actions and beliefs. To be 100% upfront, weighing these matters of morality (especially when different aspects of morality are pulling you in opposite directions) is hard work. It is very taxing. It is difficult to handle the dissonance of the situation, especially when that situation requires you to choose which aspect of morality is more important.

Well, one easy way to quickly deal with all of this is to select an aspect of morality which will always be most important. Another way to make these moral decision making processes easier is to have the most important aspect be something that is unambiguous. It is difficult to draw a clear line on harm, liberty, fairness, and sanctity. Loyalty and authority tend to be much more clear. Sure, if there is disagreement on a matter within the group or among leaders then the loyalty and authoritative backing of the matter is unclear. However, more often than not what is and isn’t loyal and what is and isn’t backed by authority is clear.

So how can we make it foolproof such that we need not think about morality or be required to wrestle with it? What if our Authority is infallible? If we place authority über alles, and said authority will never direct you to do wrong, then you’ve done it! You no longer need to go through those horrible wrestles of morality. You have a list of statements about various actions. If the action is on the list, you have your answer. “And what if something isn’t on the list?” you might ask. Well, if authority said nothing about it, it probably isn’t important so do whatever you want. No more wrestling. No more ambiguity.

We can hear conflicting messages from leaders about the degree to which we should surrender our personal evaluation of morality to authority:

“Always keep your eye on the President of the church, and if he ever tells you to do anything, even if it is wrong, and you do it, the lord will bless you for it but you don’t need to worry. The lord will never let his mouthpiece lead the people astray.”

-President Marion G. Romney (of the first presidency), quoting LDS President (and prophet) Heber J. Grant “Conference Report” Oct. 1960 p. 78

“President Wilford Woodruff is a man of wisdom and experience, and we respect him, but we do not believe his personal views or utterances are revelations from God; and when ‘Thus saith the Lord’, comes from him, the saints investigate it: they do not shut their eyes and take it down like a pill.”

-Apostle Charles W. Penrose (later served in the First Presidency) (Millennial Star 54:191)

There has long been a portion of individuals and leaders in Mormonism which will push the view that there are no moral wrestles. One need only look at the list of statements to see if it is right or wrong. The only struggles such a mindset allows is the struggle to choose to do the “right” thing in the list, or to not do the “wrong” thing on the list. Basically, will you choose to force yourself to always act the same way in any circumstance? Will you do as listed? This approach reduces morality solely to a matter of will. There is no thinking involved. No intelligence is needed. Just follow the list. Are you capable of making yourself do exactly as you are told?

Luckily there have also been strains of the importance determining what is or isn’t right in a particular set of circumstances. Brigham Young had an interesting quote about this issue:

Now those men, or those women, who know no more about the power of God, and the influences of the Holy Spirit, than to be led entirely by another person, suspending their own understanding, and pinning their faith upon another’s sleeve, will never be capable of entering into the celestial glory, to be crowned as they anticipate; they will never be capable of becoming Gods. They cannot rule themselves, to say nothing of ruling others, but they must be dictated to in every trifle, like a child. They cannot control themselves in the least, but James, Peter, or somebody else must control them. They never can become Gods, nor be crowned as rulers with glory, immortality, and eternal lives. They never can hold sceptres of glory, majesty, and power in the celestial kingdom.

It would seem that God will hold us accountable for how we follow our conscience. Another way of viewing it is how we follow God the Spirit. If we feel moved to do something, but it is contrary to what church leaders have said, what do we do? Do we consider God the Spirit or church leaders to be a higher authority? If you have experienced this, it is likely that you questioned the prompting thinking it was just one of your passing thoughts. Sometimes when asking such a question, logic is applied in this manner:

Prompting says A –> Leaders say not A –> Therefore Prompting A is wrong.

Maybe at times the “prompting” was really just you being too lazy to do the moral (or not do the immoral) thing. You need to figure that out. It will be hard. You will have to do some honest self-reflection. You should not abstain from this process. You will grow from the experience.

So how do the Milgram experiments play into this? Well, for many (and by many I mean less than 35%) it took the authority telling them that they had no choice before they were willing to finally tip their decision-making scales away from authority and towards caring for the learner. “It is absolutely essential” didn’t tip the scale. Semantics matter. If authority implies the necessity, even declares it absolutely essential that you do something, the weight of their authority is maintained. In other words, it takes much more heavy handedness from authority to make someone question it than I had previously assumed. I think the general assumption is that if authority is too overbearing then the people will push back. However, the Milgram experiments seem to show that while there may be push back, it’s not until authority claims that there is no choice that people completely refuse.

There is one last aspect of the experiments which has a lesson for us. I’m sure you’ve been thinking “why would people keep shocking others when they felt conflicted about it because of the serious harm they were causing?” Were they being ‘blindly obedient?’ It seems that the answer is actually no. If the subjects thought that there was some “greater good” being accomplished (ie, pushing forward scientific knowledge) they were willing to suspend their moral judgement and obey the leader. If it wasn’t likely to push forward this greater cause, they were less likely to obey and more likely to use their own moral judgement. This was evidenced in the surveys conducted just after the experiments. Those who went all the way explained that they were willing to participate in an important experiment and that research must be done to further progress. Maybe take a moment and just let that sink in.

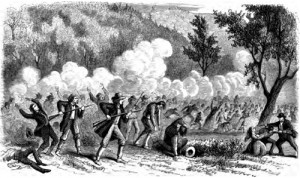

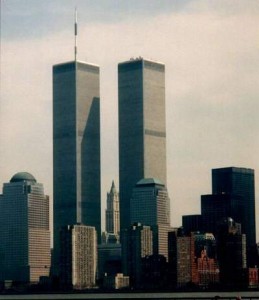

If someone thinks that the harm, the pain, the evil they are causing is justifiable in order to accomplish a “greater good” as directed by authority, what implications does that have? If you believe that God wants something to be done, that is perhaps the “greatest good” psychologically. So if the harm you are causing others is because you think that harm is what God wants, you are capable of doing some horrific things. September 11th is a poignant example. I don’t only mean 9/11/2001, I also mean 9/11/1857. By following the counsel of their religious leaders, a group of men slaughtered men, women, and children. This is a lesson which must be internalized. Follow your promptings.

If someone thinks that the harm, the pain, the evil they are causing is justifiable in order to accomplish a “greater good” as directed by authority, what implications does that have? If you believe that God wants something to be done, that is perhaps the “greatest good” psychologically. So if the harm you are causing others is because you think that harm is what God wants, you are capable of doing some horrific things. September 11th is a poignant example. I don’t only mean 9/11/2001, I also mean 9/11/1857. By following the counsel of their religious leaders, a group of men slaughtered men, women, and children. This is a lesson which must be internalized. Follow your promptings.

As the General Conference of the church is about to occur, let’s remember investigate the words of our leaders. Even when a statement from the President is prefaced with “Thus saith the Lord” let’s investigate it. Let’s exercise our agency. Let’s seek our own confirmations. Let’s engage in the spiritual/moral wrestling which is necessary for spiritual/moral growth. If we take away only one lesson from these experiments, let it be to act according to our own conscience and spiritual promptings. If we do, we will be closer to realizing the goal of Moses, Joseph Smith, and many others: that all the Lord’s people were prophets.

Fantastic insight (and a little scary). Thanks for all three of these posts.

Great series. Maybe you’ll do the Stanford Prison Experiment next??

One point I don’t think you made is that the only people who heard the 4th phrase from the Experimenter were the people who kept resisting throughout the first three phrases. I wonder if only the minority of people who were obstinate enough to start and continue arguing with the authority figure were the ones predisposed to be bothered enough to be pushed over the edge by being told they had no other choice. If I remember right, the majority of the Teachers never heard that 4th prod. I guess I’m wondering if the majority who went along with the Experimenter would have been as affected by being told they had no choice. Hope that makes sense.

I think it boosts the idea that positive change in the world and in the church depends upon people who are ready to question authority like Charles Penrose did. (And we as parents need to suck it up and allow and encourage our kids to question us, so that they’ll keep doing it with other authority figures.)

I stand with you and Milgram on the Subversion side of the line.