“I think we risk becoming the best informed society that has ever died of ignorance”

-Reuben Blades

Information has no power to convince. It can’t motivate us to action or modify behavior. Convincing, or conversion, is an emotional process. Info + emotion = conversion. The resulting ideals become our opinions. Sometimes opinions are overbalanced on the emotional side to the extent that we are willing to ignore information or evidence, but if conversion is based too heavily on emotion, it is unlikely that it will be beneficial. Without further factual and emotional input, it will remain shallow and subject to collapse with challenge. Since we are constantly presented with information, claiming truth, we’ve got to come up with a way to figure out what is important. What can improve us and benefit those within our sphere of influence? Otherwise we will remain confused, without convictions. The easy, Sunday School answer is the Holy Ghost which is okay, as a start, but “Holy Ghost” is only a title or phrase describing an idea, unless we are able to develop a more personal understanding. What or who is the Holy Ghost to me? What will he/ she tell me and why? What does that feel like for me? When we sincerely ask these questions and earnestly watch for guidance we can feel the communication of Gods desire for us.

In the mid 1950’s, psychologist Leon Festinger was studying the phenomenon of conversion. He became aware of a religious group called “The Seekers” in Chicago. They were led by the charismatic Dorothy Martin who claimed to receive communication, through automatic writing, from aliens on the planet “Clarion”. She predicted that the United States would be destroyed by a cataclysmic flood on December 21, 1954. She convinced her followers that they would be rescued by aliens in their flying saucer. Members left jobs and homes, abandoned spouses and families in order to participate. They even went so far as to remove all metal objects, tearing out zippers and under-wires from bras which they thought would interfere with the spaceship. Festinger suspected that the aliens wouldn’t show up and he was interested in how the group members would respond. He infiltrated the group and awaited the date. It came and went, no saucers appeared, but their belief continued. Faced with obvious evidence that contradicted their convictions they had to either abandon their belief or resolve the resulting dissonance. Their leader received another “revelation” declaring that their demonstration of faith had averted the imminent disaster. Problem solved. The Seekers were relying completely on an emotional conversion. When it was proven to be false, they invented a new mythology and attached their faith to that with deeper conviction than they had before. The seeming devastation of their belief only seemed to make them more certain.

When seeming inconsistencies occur between ideas in a group, either because of new information, the personal experiences of individual members, or misunderstanding of ideas, the resulting discomfort is what Fesinger called “Cognitive Dissonance“. This dilemma depends on the following conditions:

- Members must hold convictions deep enough to affect their behavior.

- The individual member must have made sacrifices to achieve the devotion required of the group.

- The belief must be specific enough to be supported or refuted by physical or historical evidence.

- The belief must then, be in conflict with encountered evidence.

- Individual members must have social support. The phenomenon rarely occurs with individuals acting alone.

To escape the discomfort, members will look for a way to restore harmony without abandoning strongly held convictions. This often leads to wildly creative mythologies and, in the worst cases, psychologically damaging attitudes and organizational policies. It’s important to note that this condition does not require a belief to actually be false, it just requires the perception of falsehood. Misunderstanding is often the cause of dissonance. In order to re-establish cognitive consonance, members must be willing to accept the new mythology, or loosen their grasp on convictions in a way that allows them to examine their accuracy and accept further understanding. Easier said than done.

Church members who have allowed their belief and subsequent behavior to be dictated by outside influence, often find the introduction of contradictory information hard to bear. All of us, in process of conversion, find ourselves in that position. We depend on others for the information that sparks our interest and sets us on the path of spiritual development. Eventually, we stand at the proverbial crossroads where what we believe comes into conflict with some new information and our continued path lies beyond it’s resolution. The situation demands a choice, the pain imposes urgency. Do we face the trauma of abandoning belief or seek to reconcile the dissonance in some other way? How do we analyze and who do we trust as a guide? Can we trust ourselves?

Most of us are likely to believe what we want to, if we can reasonably rationalize the belief. In other words, even if we think we are being objective, we are choosing to see evidence that supports what we find emotionally appealing. This is commonly referred to as “Motivated reasoning” or a biased process for evaluating the validity, applicability or relevance of a proposed belief. There must be a way to distinguish between reasoning and rationalizing. It makes sense that a loving God, who wants us to develop along a path of truth, would provide a way for us to discern it. There is obviously no certainty and it is ultimately our choice. We seek belief in principles that reinforce our purest values and when we do, God confirms our choices with emotional rewards; happiness, joy, peace. The presence of those factors reassures us that we are moving toward Him.

“The call to faith…is not some test of a coy God waiting to see if we ‘get it right’. It is the only summons, issued under the only conditions,which can allow us to fully reveal who we are, what we most love, and what we devoutly desire.”

-Terryl and Fiona Givens “The God Who Weeps” p5

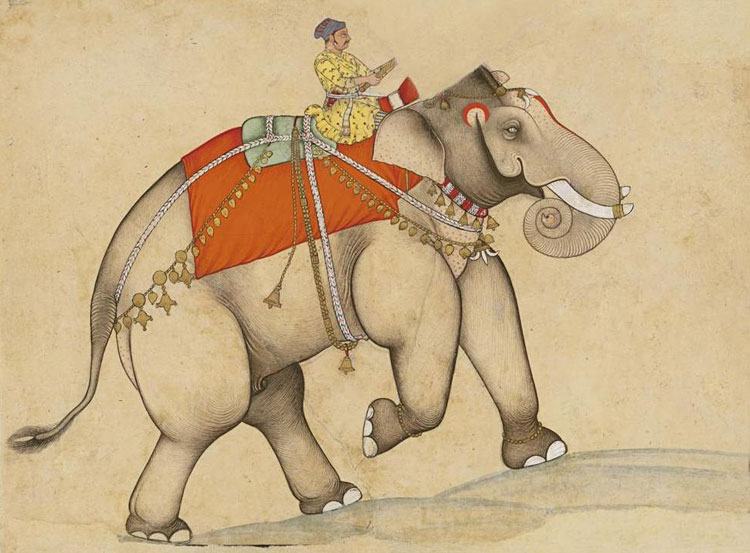

In his recent post, Michael Barker mentioned Jonathan Haidt‘s famous “Elephant and Rider Metaphor”, in which (simply put) the rider represents reason and the elephant represents emotion. Now, I don’t have any experience riding or steering an elephant but I would imagine that success depends on the relationship between the rider and the beast. How well does Rider know Elephant? Does he know what Elephant is capable of, constructively and otherwise? Does Elephant trust Rider? The allegory helps us to consider and understand the relationship between emotion and logic within ourselves. Each promotes a different response to conditions and each comes from a different part of the brain. Moving in the right spiritual direction depends on our ability to access both, in balance, but clearly, Rider speaks a different language than Elephant. The influence that we have named “The Holy Ghost” is the translator. John 14: 26

Much of my thinking for this post came from this article:

Thanks. Exactly where I am right now in the balancing act. Not easy to navigate at times but grateful for the ride:)

I study science but then study mythology. I study archaeology/history/culture and then study scripture/great philosophers/meditation for further balancing. If I get to heavy on the intellect, I feel brain overload. If I neglect my internal spiritual landscape, I feel drained and in need of replenishment.

Fabulous post Daniel T. Lewis! Super insightful.