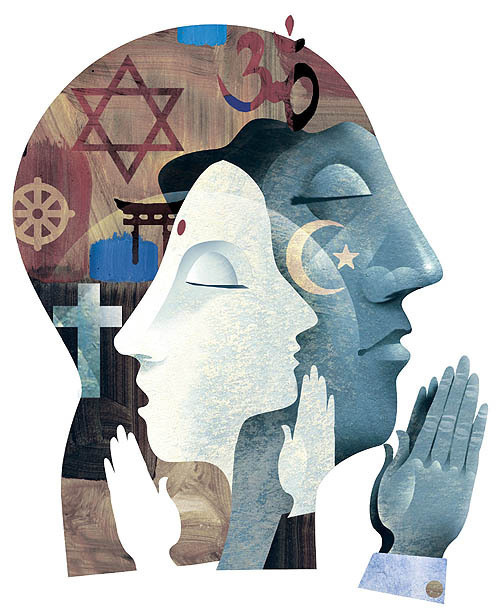

If there is one thing that makes religion unpopular in today’s pluralistic society, it is the idea of claiming access to exclusive truth. On my mission I learned firsthand how the act of sending someone to your door is deeply offensive to so many people. It is one reason religion is just something you are not supposed to talk about, in the interest of keeping peace. Religion is simultaneously deeply personal and deeply divisive.

When you already feel a strong spiritual bond of community, spirituality and faith, being proselyted by others is seen as an assault on everything you stand for. At the same time, helping others see what you have and sharing it also becomes important the more invested you become and the more joy you find in your faith. Calm assurance that you are “right” has been used to justify coercion, violence and even genocide against outsiders throughout history. This in spite of the fact that such actions are thoroughly condemned in the holy writings of all the faiths involved.

Religions are now routinely beat over the head because of this idea. For a religion to be a religion it has to make some claim to truth or authority, otherwise it becomes a set of hollow set of customs and ritual. Yet, one could easily ask, “if you guys have it all figured out, why is God so inefficient as to include a just a small minority of his children in his plan?” The question becomes Is it true that you believe only (Christians, Mormons, Muslims, Jews, etc.) go to heaven. The implication is intuitive. How would God justify privileging a certain group over everyone else? It seems unjust and tyrannical. At the same time, why does your faith matter if this is not true?

The act of proselyting becomes an assertion that you have something better than the other and they will resent it. It is only human to resent it. On the other hand, If you really do believe an exclusive truth claim, you very well better be spreading the message because those others are in trouble if you don’t. Proselyting becomes a labor of simultaneous arrogance and concern.

In order to solve this conundrum, many take the “All mountains lead to mount Fuji” approach. Mohandas Ghandi certainly saw it this way. He once stated, “My effort should never be to undermine another’s faith but to make him a better follower of his own faith”

It seems he backed this up in his life. Speaking of Christianity he said, ”I like your Christ. I do not like your Christians. Your Christians are so unlike your Christ. The materialism of affluent Christian countries appears to contradict the claims of Jesus Christ that says it’s not possible to worship both Mammon and God at the same time.” Pretty challenging and confrontational and yet, in a way that asks people to live their own faith’s teachings. I think it’s brilliant but universalism is also very tricky. Inclusiveness as value can take on an orthodoxy and exclusiveness of its own. By proclaiming all religions lead to God it seems to me one has to declare all exclusive truth claims completely false. It can lead to it’s own intolerance of such truth claims, which are found in the orthodoxy of every faith. Thus belief in all faiths in a sense requires disbelief in all of them as well. “Spiritual, but not religious” has become the popular self description of those ascribing to the orthodoxy of inclusivity.

This path is easier in Eastern traditions because they don’t necessarily believe in God as a being, per say. Thus, living, ethics, spirituality, and practice become the important components of religion and faith, but they really become more relative to what you understand truth to be. It can become somewhat fuzzy. The monotheistic Abrahamic Faiths, on the other hand, do claim a God above all other Gods, and Lord of Lords. They do this for a very good reason. Ethics and spirituality are meaningful insofar as there is an absolute right and a wrong. Otherwise any position can be rationalized. There has to be an ideal. The monotheistic idea of God defines this. So how on Earth do we reconcile an ideal of authoritative truth with the sneaky temptation to be “right” for the sake of being the right ones. I admit it is a fine line.

Can someone make these kinds of claims and still hold respect for the culture, tradition, faith, spirituality and truth claims of others. I know some may disagree with me but outrageous as it may seem, I think so. Mormonism has a mechanism in place, baptisms for the dead, for helping everyone enter a covenant with Christ regardless of whether they ever had any chance to learn about him in this life. Many don’t like this idea, envisioning it as a kind of cultural post-mortal warfare, but I don’t think that is the way it works at all.

To be fair, the value of this practice is clearest to those who accept that Christ is the way, the truth and the life, believing that no man comes to the Father but by him. Christianity is exclusive, no two ways about it. What baptism for the dead allows us to do is to accept the absolute necessity of Christ but offer it to everyone through space and time, in this life or the next. I like to imagine that in the next life we might be able to see past the tribal attitudes that make this idea so horrifying to Non-Christians. If we lived before we came to Earth and we are to return, will it really be so awful after this life to accept Christ when we can see him, remember him and know him? Will it be so awful to recognize the need for him? The answer to these questions is absolutely, it’s horrifying— if that knowledge condemns us to endless fire and torment. God would be a monster or tyrant who capriciously shares his plan with a very privileged few of his children and casts off the rest. Mormonism is unique among Christianity in finding a workaround to this problem. I think we deserve some credit where credit is due.

So, in Mormonism, accepting Christ can be done in this life or the next. It is always done voluntarily. While the ordinances may be performed by proxies who are completely and sadly oblivious to the spiritual heritage and life of the person they proxy for, I think nonetheless that the idea comes from a good place. Ultimately, the idea is that everyone who ever lived (past childhood) will be baptized and receive whatever ordinance they need. Of course if everyone will eventually have the ordinances done for themselves, it does beg the question of why the ordinances are necessary at all. We are talking about the vast majority of mankind receiving these by proxy after mortality. After all, Mormons are a fraction of a fraction of the population of Earth right now and Christians have never been a majority.

This is where I think the symbolism of these ordinances hits something deep and profound. You see, we are taught that the hearts of the children must be bound to the fathers and the fathers to the children to avoid some kind of curse. Richard Bushman, in talking about sealing as envisioned by Joseph Smith, wrote, “He wanted to lock people into relationships–not necessarily sentimental relationships but ones of mutual obligation and cooperation.” In short, God wants to save all the human family as his people, bound to each other. In Mormonism we take another exclusive concept, the children of Israel, God’s covenant people, and explain that this group was scattered all across the Earth. In other words, the lineage of Israel is now everywhere, in all nations, tongues, kindreds and people. We all become his chosen to eventually be gathered back unto him.

I prefer to think that in the next life, we may see past labels that currently divide us. That cultural constructs that we now fight over incessantly will have the truest parts of them opened up, and the less true discarded. Every religion and tradition, Mormonism included, provides only an incomplete picture of the nature of God and meaning of existence. We cannot comprehend every mystery yet. We all have ideas we will have to get rid of in order to move along toward truth. In Mormonism as I see it, in the next life Mormons won’t exist. Baptists, Methodists, Shia, Sunnis, Sufis, Jews, Catholics, Buddhists, Confucians, Hindus, none of these will exist in the exact form they are practiced here. Instead we will just be children of God, the human family. All of these groups have changed in their beliefs and practices to some degree over their history, and will continue to change in the future if they are to remain vibrant. I believe that in the next life, all will retain their truest, most sublime parts, casting off all the imperfect understanding, cultural limitations and folklore. Best of all, these truths will be for all of us to share. I hold to this idea of a bigger, more universal God because I am Mormon, not in spite of it.

>The monotheistic Abrahamic Faiths, on the other hand, do claim a God above all other Gods, and Lord of Lords. They do this for a very good reason. Ethics and spirituality are meaningful insofar as there is an absolute right and a wrong. Otherwise any position can be rationalized.

Actually, a monotheistic ego-based Lord can and does result in the kind of moral ambiguity you describe. All one needs to do to rationalize any action is to claim that the Lord of Lords commanded it, and it is therefore right.

Not every action, however, can be adequately defended by reason or logic.

Okay, here’s a philosophical hand grenade: There exists an unpleasant thought that lurks in the deepest recesses of the human mind, an unwelcome visitor that sometimes slinks from the shadows of the sub-conscious and sharp- elbows its way into the crowded walkways of cognition . It’s a dreaded though, a thought that has vexed humankind for millennia. And whenever it emerges, it’s hastily thrust back to the cerebral pit from whence it came, and the balm of religion is quickly applied to sooth the spiritual bruises sustained in the encounter. But what if this thought were allowed to remain, to poke, flail and inflict it’s pain? What if it were recognized and accepted as an inevitable reality? Would it’s recognition likely cause untold fear and anxiety ? Probably, because this unwelcome Anubis, this beast from the threshold flatly rejects a critical doctrine that societies and religions– in particular– have attempted to inculcate (and successfully so) in the human psyche from time immemorial. So what is this psychic monster that is so terrifying and, for many, unspeakable ? Quite simply It’s the likely probability that there exists NO afterlife, that when one dies that’s the end. This jarring realization would likely shatter the hopes and dreams of millions who depend upon and even DEMAND eternal life as a reward for their mortal existence. Harsh? Maybe. Reality? Probably.

If you want to read an in-depth analysis of this subject then I recommend THE ILLUSION OF IMMORTALITY, by Corliss Lamont, 1935. Lamont’s narrative is straightforward and reasonable. I particularly like this quote:

“The proposition that if we wish a thing strongly enough, therefore we can depend on it existing or coming to pass is, of course, the weakest reed upon which to lean. Were it a sound principle, the world would long ago have become a Utopia of universal happiness, and death itself would have been entirely abolished. But it is fairly clear that existence does not coincide with that grand old fairy tale where one puts on a magic wishing cap and then makes all one’s dreams come true, To say with Emerson that our dissatisfaction with the idea of human mortality proves that there must be immortality completely overlooks the consideration that throughout all history the truth, both in big things and little, has frequently dissatisfied and made unhappy any number of people.”

I have come to terms with the concept of human mortality, even though it goes against everything I have been previously taught and at one time accepted.

So my admonition is this: wake up and throw off the scales of ignorance and superstition. Shed the illusion of eternal life and cease to” dream of your mansions on high” because this life, the here and now, is your one and only life, a life that an incomprehensible and seemingly indifferent universe has somehow granted you, albeit for a brief time. Don’t waste this precious allotment wishing and hoping for heaven. It’s not waiting for us. But instead: love, learn, think, create, assist, comfort, appreciate, listen, dream, and stand in awe. If you do these things you will have lived your life to the fullest and you will continue to live on in the memories of family and friends and, perhaps, even someone who never knew you personally. LIFE then will have a purpose and be its own reward.

The idea of baptisms for the dead (providing a way for ALL of God’s children to receive the necessary ordinance to be saved)- or any work for the dead – completely fell apart for me when I started traveling to Africa frequently for humanitarian aid. I started to get a better picture of the massive number of people who have lived and died without a single trace. No paperwork, no records, nothing. When I asked a leader about that, I was told that God can make it right in the end. I then asked if He could make it right for the huge number of spirits whose names can never be found, whose time on this earth is untraceable, why can’t he do the same for the rest of us? Or why wouldn’t he do the same for the rest of us?

Far more thoughtful and well-reasoned than the last article on exclusivity. I’d be interested in Nelson’s view on this.

Verl, this is like saying that the idea of missionary work completely feel apart for you once you learned that God will give everyone in the Spirit World a chance. I don’t get it.