A SURVEY & CRITIQUE OF THE DIFFERENT RESURRECTION HYPOTHESIS PART V: HUME’S ABJECT FAILURE

Click here to read Part I

Click here to read Part II

Click here to read Part III

Click here to read Part IV

A case for Jesus’ resurrection historically has two elements to it. First, we must establish the basic facts to be explained. Secondly, we must figure out what is the best explanation of those facts. We saw that with respect to the facts to be explained, there is in large measure, something of a consensus among New Testament scholars today. These are:

- Pilate, the Procurator, sentenced Jesus of Nazareth to death by crucifixion

- Jesus died

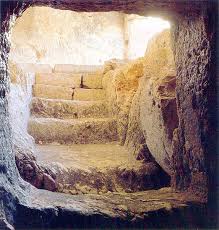

- After His crucifixion, Jesus was buried in a tomb by a member of the Jewish Sanhedrin named Joseph of Arimathea.

- The discovery of Jesus’ empty tomb

- On multiple occasions and under various circumstances, different individuals and groups of people experienced appearances of Jesus alive from the dead.

- The original disciples suddenly and sincerely believed that Jesus was risen from the dead despite their having every predisposition to the contrary.

The question at hand now is, what is the best explanation of these facts? The explanation that the disciples originally gave was that God had resurrected Jesus from the dead. Is this the best explanation of what happened?

Skeptic’s reservation with the resurrection hypothesis are not historical reservations. They are philosophical reservations. This explanation is not rejected on its historical merits or demerits, but because of philosophical objections to it. For example, Bart Ehrman, agrees with all of the facts that have been mentioned, but says the historian cannot adopt the resurrection hypothesis as the best explanation “apart” from the philosophical question of whether miracles exist. He says that even if the resurrection actually happened, the historian cannot infer that it is the best explanation of the facts. Why not? His reason is philosophical. He says a miracle, by definition, is the most improbable thing that could happen. Therefore, no amount of historical evidence could go to establish a miraculous explanation, like God raising Jesus from the dead. In fact, Dr. Ehrman believes that to think historical evidence could establish this is an utter a self -contradiction. It would just simply be self-contradictory to say the lease probable event is the most probable event.

If one knows their history of philosophy, it will be recognized that this objection by Dr. Ehrman is nothing new. This is the objection that was presented by the Scottish skeptic, David Hume in the 1700s, in his essay on miracles. Ehrman simply presents a version of Hume’s argument against the identification of a miracle. According to Hume, all the evidence of mankind’s experience has established the laws of nature. The laws of nature are true, including that dead men don’t rise from the dead. Hume therefore believed that no amount of testimony to an event which is a violation of nature’s laws, could ever be the best explanation of the evidence. It would simply be overwhelmed or counter-balanced by all of the evidence for the laws of nature allegedly violated by the miracle. Therefore, you could never be justified in inferring the best explanation of the facts is that God raised Jesus from the dead because that is so improbable.

This Humean objection has entered into popular culture. All have heard the following claim: “Extraordinary events require extraordinary evidence.” The implication of course for the resurrection is that the evidence is not strong enough to establish that hypothesis. This is basically a reprise of David Hume’s objection. Therefore, you could never have enough evidence to establish such an extraordinary event as the resurrection of Jesus. What we have here is just a popular slogan that incapsulates David Hume’s argument. Wouldn’t this possibly argue against natural events?

Suppose someone, from the tropics, goes to the polar ice cap. This traveler reports that water can exist in the form of a solid. The people in the tropics would not believe the traveler’s eye witness account because this would go against all the evidence and laws that the people of the tropics have ever seen. Therefore, applying Hume’s principle, those living in the tropics should never believe the traveler’s eyewitness reports of ice. Hume admits this. One should not believe this because it contradicts the rules of natural law that was available to him. This should make one feel a little uncomfortable about this view because it is going to rule out, not just super-natural events, but also ordinary, natural events. You could never discover anything new that you thought initially were against the laws of nature.

that the people of the tropics have ever seen. Therefore, applying Hume’s principle, those living in the tropics should never believe the traveler’s eyewitness reports of ice. Hume admits this. One should not believe this because it contradicts the rules of natural law that was available to him. This should make one feel a little uncomfortable about this view because it is going to rule out, not just super-natural events, but also ordinary, natural events. You could never discover anything new that you thought initially were against the laws of nature.

It must be understood that Hume’s and Ehrman’s argument is not that miracles don’t occur, but is against the identification of a miracle. The argument is that, if a miracle occurred, you would never be justified in inferring that a miracle occurred because it will always be more probable, by the very nature of the case, that the event is not miraculous; there is some natural explanation. In one sense, both Eherman and Hume, would admit this might lead you to mistakenly miss a miracle. But, because of the nature of historical studies, you wouldn’t be able to spot it. It is not an argument against the existence of miracles, it is against the possibility of identifying a miracle. Therefore, by implication, it is an argument against anyone ever believing that Jesus was raised from the dead. Even if God did raise Jesus from the dead, one would not be justified in believing that. It seems to be saying that the rarity of an event implies improbability.

Another problem is that the historian has to be open to the uniqueness of the past. To impose the grid of the present over the past, is not to really be interested in doing genuine history. One has to be open to novelty, the unexpected, and to follow the evidence wherever it may lead; it might lead you to revise some of your judgements that you previously had.

Hume’s Abject Failure

As common-sensical as Hume’s argument sounds, it is demonstrably false. John Earman, University Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Pittsburgh, who is not a Christian, but is agnostic, wrote a book called, Hume’s Abject Failure: The Argument Against Miracles. Earman says there are arguments in philosophy which are failures and we expect those. In the case of Hume, Earman says it is an abject failure. Probability theorists after Hume wrestled with what it would take to establish the fact of highly improbable events. What kind of evidence is required to establish a highly improbable event? What the probability theorists soon realized is that you cannot say, “Extraordinary events require extraordinary evidence.” It is too simplistic.

David Hume believed if an event was sufficiently improbable, the improbability of the event would simply overwhelm the reliability of the witnesses. With modern probability theorists, it became clear that you could not just consider the reliability of the witnesses. Here is an example: take an evening news report that states that there is a winner of the lottery. When you think about it, the report of just that person winning the lottery, is an event of extraordinary improbability; millions and millions to one that that person picked the correct number(s). If extraordinary events did require extraordinary evidence, you should never believe the broadcast on the evening news of that specific person winning the lottery. Suppose that the reliability of the news is 99.9% accurate. It would none-the-less be overwhelmed by the improbability of the event. Therefore, on Hume’s and Ehrman’s argument, we should be skeptical of the report on the evening news and we should not believe that person had the winning pick because the event is so improbable. No matter how reliable the witnesses are, it could not go to establish such an improbable event. The improbability of that event occurring is so great that it will swamp the reliability of the evening news; thus you should not believe the evening news. If you simply weigh the improbability of the event against the reliability of the witness, you would be barred from believing many ordinary natural events like someone winning the lottery. Such a conclusion is absurd. What is missing in Hume’s argument?

What probability theorists came to realize is that you cannot simply say, “extraordinary events require extraordinary evidence.” Probability theorists realized you must not only consider the reliability of the witnesses and how probable or improbable the event is relative to our background knowledge of the world, but that you must also consider the probability of the evidence for the event occurring if the event had not occurred. What is the probability that if the event had not  occurred, that we would have the testimony or the evidence that we do? How probable is it that the evening news would announce a winner of the lottery, if no one had won the lottery? If that probability is sufficiently low, that would go to outbalance the improbability of the event itself. Hume’s skepticism is based on the insufficient understanding of probability calculus. When probability theorists talk about probabilities of events, they always talk about the probability of some event relative to some other body of information.

occurred, that we would have the testimony or the evidence that we do? How probable is it that the evening news would announce a winner of the lottery, if no one had won the lottery? If that probability is sufficiently low, that would go to outbalance the improbability of the event itself. Hume’s skepticism is based on the insufficient understanding of probability calculus. When probability theorists talk about probabilities of events, they always talk about the probability of some event relative to some other body of information.

In the case of the resurrection, what is the probability that if Jesus of Nazareth did not rise from the dead, we would have the evidence of the empty tomb, the post-mortem appearances, and the origin of the disciples belief in Jesus’ resurrection? If Jesus had not risen, it can be argued that it is highly improbable that you would have the evidence for the empty tomb, etc. When you consider the full probability calculus, it turns out that an extraordinary event may not require extraordinary evidence if that evidence is highly unlikely to have been given if the event had not taken place. This is how probability theorists estimate the probability of certain events.

Intrinsic Probability and Background Information

There appears to be yet another problem with Hume’s assessment of miracles, specifically with the resurrection of Jesus. What is the probability of the resurrection of Jesus, relative to our background knowledge of the world (this is our knowledge of the world and the laws of nature and nature’s productive capacities, etc and all other knowledge we have apart from the specific evidence we have for the resurrection of Jesus) and the specific evidence in this case? First we have to look at the probability of the resurrection relative to the background knowledge alone (taking away any specific evidence for the resurrection). This is called the intrinsic probability of the resurrection. We also have to look at the probability of the evidence given our background information (intrinsic probability) and that the resurrection did occur. What is the probability of the evidence given our background knowledge and the occurrence of the resurrection? That is to say, given that the resurrection did occur, how probable does it make the empty tomb, the post-mortem appearances, etc? This is often called the explanatory power of the resurrection hypothesis.

One also has to consider the intrinsic probability of no resurrection on the background information. We also have to look at the probability of the evidence on the background information; how well can you explain the given evidence (empty tomb, etc) if no resurrection took place? These two factors (no resurrection on the background information and no resurrection given the evidence for the resurrection) will represent the intrinsic probability of the explanatory power of the resurrection not taking place. These factors basically will represent the probability of the explanatory power of all the naturalistic alternatives to the resurrection (the Swoon Theory, the Apparent death theory, etc). What is their (the naturalistic alternatives) intrinsic probability relative to the background information and what is their explanatory power? How well do they explain the evidence?

We can now see where Hume’s argument is fallacious. When Hume considered the probability of the resurrection on the background knowledge and evidence, the only factor he considered was the intrinsic probability of the resurrection. What he argued was that the resurrection of Jesus is highly improbable given our background knowledge of the laws of nature of the natural world. Because that is so low, the probability of the resurrection on the background evidence is low and so it cannot be believed.

This is a fallacious conclusion because the probability of the resurrection is not dependent upon the background evidence alone. What also has to be taken into account is the probability of the naturalistic explanations relative to the resurrection hypothesis. If the probability of those (the naturalistic alternatives) are sufficiently low, they will out-balance any intrinsic improbability in the resurrection itself. What this means is, the more improbable the naturalistic alternatives are, the higher the probability of the resurrection itself is. Hume only looked at the intrinsic probability of the resurrection and ignored the intrinsic probability and explanatory power of the naturalistic alternatives to the resurrection. This is what John Earman calls Hume’s abject failure. This is the same mistake made by Bart Ehrman who says the resurrection is improbable simply because the intrinsic probability of the resurrection is low. The question is not in the intrinsic probability of the resurrection alone. The question is the intrinsic probability of the resurrection given the specific evidence. The intrinsic probability alone might be low, but the intrinsic probability plus the specific evidence, makes the resurrection more probable than the intrinsic probability alone.

Relative to the background information alone, the resurrection of Jesus is enormously improbable. Is this a justifiable assumption? Why think the resurrection of Jesus is improbable on the background information alone? It is very important to specify exactly what the resurrection hypothesis is. The resurrection hypothesis is not the hypothesis that Jesus was raised naturally from the dead. That hypothesis in fantastically improbable. That all the cells in Jesus’ dead body would spontaneously come back to life again is so biologically and medically improbable that it can be said to be naturally improbable. This is the reason why we consider the resurrection a miracle; because it is naturally impossible. The resurrection hypothesis is not that Jesus rose naturally from the dead, but is that God raised Jesus from the dead. There is no reason to think that is highly improbable. Why should it be thought highly improbable to think God raised Jesus from the dead?

It seems that either one has to prove God’s existence improbable or that God’s wanting to raise Jesus from the dead improbable. Unless one of those two propositions can be proven, there is no way to say that God did not raise Jesus from the dead. The person that wants to claim the intrinsic improbability of the resurrection would have to show it highly improbable that God exists or its highly improbable that God would want to raise Jesus from the dead. How would someone have that kind of knowledge to prove that? The best someone can do is to be agnostic about it; one cannot say it is improbable.

Hume’s question, which is more probable, that Jesus resurrected or that the witnesses were lying, is just a trick question. It is certainly true that the resurrection is more miraculous given that it is supernatural. There is an external cause necessary to bring about the resurrection of Jesus. In that sense, yes it is more miraculous. But, it is not more improbable. If you were to ask which is more improbable, that the witnesses should be lying or mistaken or that Jesus rose from the dead? I would argue that it is more improbable that the witnesses were lying or mistaken, given the specific evidence that we have. Don’t confuse miraculousness with probability. Therefore, Hume’s argument is recognized today to be fallacious. There is yet another factor that Hume failed to consider.

Hume also neglected to consider how probability is augmented when you have multiple witnesses to the same event. If you have multiple witnesses to the same event, then you add the probabilities together. Suppose you have two witnesses that are 99% reliable. That means you have one chance out of one-hundred that one of them is mistaken. If you have two of them, it is not two chances out of one-hundred. The chances of both being mistaken are only one out of ten-thousand. If you have three witnesses that are 99% reliable, the chances of them being wrong is one out of one-million. When you have multiple witnesses, you add the probabilities together and you quickly overcome any intrinsic improbability that you think might be involved in the resurrection itself. Even if each of the individual attestations, by themselves, had a low probability, the cumulative probability would still be high.

Rare Red Cars

The skeptic might say that such an event is very rare. That, however, does not mean that it is improbable. One cannot equate improbability with frequency. As John Earman points out in his book, Hume’s Abject Failure, you cannot use frequency as a theory of probability. Earman gives the example of scientists trying to find an event of proton decay in their nuclear research facilities. Scientists, Earman points out, are spending thousands of man hours and millions of dollars in trying to detect a single event of a proton decaying into its subconstituents; yet this has never been observed. No one has ever observed the event of proton decay. So, if one uses a frequency model of probability, that would mean the probability of this event is 0. Yet, scientist are not investing millions and millions of dollars and thousands of research hours in trying to detect an event that has a 0 probability of occurring. You cannot just use frequency as a theory of probability. This is especially evident when dealing with the decisions of a free agent.

It may be precisely because the resurrection is so rare, so singular, that God chose it to vindicate the claims of His Son; God wanted to pick a highly unusual, singular event to vindicate His Son Jesus. It is the very infrequency of the resurrection that would make it highly probable that God would raise Jesus from the dead as a demonstration that Jesus was in fact His Son and that His claims were true. One cannot make a simplistic equation between infrequency and improbability. There are no grounds to think that the improbability of the resurrection is low.

To give an illustration, suppose one goes into a car lot to buy an automobile. Suppose 99 of the 100 cars are black. There is one bright red car. If you take this as a random probability, you would say the chances are that one would drive off the lot with a black car. Suppose the person does not like black cars. He wants something more rare. In fact he choses a red car precisely because it is rare. It is because it is unusual that the red car is desired. In that case, it can be seen, the rarity of the color does not say anything at all about the probability that a black car will be bought. In this example, it would be to the contrary. It is the rarity of the red car that increases the probability that the person in this scenario will pick the red car. This shows that when we are dealing with a free agent, as opposed to just a random process, all bets are off. A free agent can do as he chooses. We are not dealing with just a randomized process here like picking balls blindly out of a lottery. When there is a card shark at the table all bets are off. With ordinary shuffling and dealing, it is just chance and random distribution. We can then ask, what is the chance that my opponent will be holding four aces? It would be very slim. Then when you learn there is a card shark sitting opposite of you, all bets are off. You are no longer dealing with a randomizing process.

To give an illustration, suppose one goes into a car lot to buy an automobile. Suppose 99 of the 100 cars are black. There is one bright red car. If you take this as a random probability, you would say the chances are that one would drive off the lot with a black car. Suppose the person does not like black cars. He wants something more rare. In fact he choses a red car precisely because it is rare. It is because it is unusual that the red car is desired. In that case, it can be seen, the rarity of the color does not say anything at all about the probability that a black car will be bought. In this example, it would be to the contrary. It is the rarity of the red car that increases the probability that the person in this scenario will pick the red car. This shows that when we are dealing with a free agent, as opposed to just a random process, all bets are off. A free agent can do as he chooses. We are not dealing with just a randomized process here like picking balls blindly out of a lottery. When there is a card shark at the table all bets are off. With ordinary shuffling and dealing, it is just chance and random distribution. We can then ask, what is the chance that my opponent will be holding four aces? It would be very slim. Then when you learn there is a card shark sitting opposite of you, all bets are off. You are no longer dealing with a randomizing process.

As pointed out earlier, with regards to God, isn’t it highly probable that in order to vindicate the radical claims of His Son, for which He was crucified, that God would pick an event of extraordinary improbability? An event that is so singular that it has never happened before in the universe and will not happen again in the universe; namely that God raised Jesus from the dead. It is precisely because of its infrequency, unusualness, and improbability of the event that makes the event highly probable that God would do such a thing to vindicate the claims of His Son. It can be seen that when working with a free agent and his decisions, you cannot use frequency as your theory of probability. To say resurrections are infrequent, and therefore highly improbable, is wrong.

For these reasons, Hume’s arguments are fallacious. Extraordinary events do not require extraordinary evidence. With regards to the resurrection, we have to compare it to the other hypothesis. We are not just punting it to God. We are asking what is the best hypothesis? The skeptic won’t even consider the supernatural. I have heard Sherlock Homes cited to defend the skeptics view, “…When you have eliminated the impossible, whatever remains, however improbable, must be the truth” (The Sign of Four, chapter 6, pg 111). If we eliminate the possiblitly of the resurrection as being true, sure the other hypothesis look more probable. Regarding the exclusion of the supernatural as a possible hypothesis, Dr. Robert M. Price, a very skeptical Bible scholar had this to say:

“If you rule out the resurrection as possible, the [other] theory starts looking pretty good. That’s exactly what the apologists say – “Why should one rule out the resurrection as impossible? Isn’t that the very thing trying to determine? Aren’t you arguing in a circle? Sure, if you rule out the resurrection, this stupid [alternative] theory starts looking probable. But it shouldn’t and therefore you shouldn’t rule out the resurrection.” That is why I never argue on this basis. I am not even motivated by it. I conscientiously hold to this criterion: I do not know what is going on in the universe. If there is a God or not, I don’t know. How could I know? I tend to think there is not, but I don’t know. But it is not a faith statement. I can’t prove it. It seems to me there is not, so I go that way. But I do not make that the basis of historical judgements. How could I? That would be ridiculous! My take on the way the world works doesn’t figure into my reckonings of what probably did or probably didn’t happen. No, you have to use other criteria for that… The notion that it can’t happen, I think “fundys” are right, that does not have a place. And you don’t need it at all. It really doesn’t change things” (Dr. Robert M. Price – Sceptical Bible Scholar and host of : The Bible Geek podcast; 3/2/12; 55).

The detractors of miracles finds themselves in a real bind here. There is no good way to prove that the probability of the resurrection on the background information is desperately low, unless they have a good argument for atheism or some good argument that if God did exist, He would not want to raise Jesus from the dead. Of course that takes us into all the arguments for and against the existence of God. The background information for the resurrection does include the different arguments for the existence of God. The resurrection on the background information is not at all improbable given the existence of God; which the background information renders likely.

We can show with high probability that God exists, but how can we show with high probability that God would raise Jesus from the dead as opposed to something else? While we can show with confidence that the probability of the resurrection is not low, I am not sure that you can prove that it is high either. These arguments are purely defensive arguments, not offensive ones. The arguments work well though against Hume and Dr. Bart Ehrman who negatively argue that miracles cannot be established by the evidence because miracles are inherently improbable and therefore no amount of evidence can go to establish that. We can answer that objection by showing the resurrection is probable. The burden of proof lies on the non-believer.

Hume and Dr. Bart Ehrman therefore stand on a precarious argument.

Next week we will look at Dr. Alvin Plantiga’s objection.

A point of clarification… Ehrman says that *apart* from the philosophical question of miracles (namely, whether miracles can exist, whether natural laws can be broken, etc), the nature of historical scholarship can never conclude that miracles occurred, *even if they are possible philosophically*, because by nature they would be the MOST improbable event, and historians can only measure probabilities/likelihood.

Ok. I edited it. Let me know if it is truer to what Dr. Ehrman has stated.

Jared,

Thanks. I am actually honored that you read the post and took time to critique it. I am trying to figure out where to put your suggested edit.

Wow. Nice work, Mike. This wasn’t an easy read for a Monday morning, but I’m glad I spent the time. I’m also glad philosophers have laid the groundwork for this type of discussion.

I liked this: “The question is the intrinsic probability of the resurrection given the specific evidence. The intrinsic probability alone might be low, but the intrinsic probability plus the specific evidence, makes the resurrection more probable than the intrinsic probability alone.”

I was especially interested in the idea that even extraordinary events are subject to natural laws and that if Jesus Christ was indeed resurrected it was via natural laws — possibly laws of which we are ignorant at this time. This is a time-honored Mormon view and although you didn’t implicitly state this as your view, the example you used fits well. And because this idea fits with my own personal view, of course, I liked it!

Go, Jesus! Go, resurrection and all that implies for the believers!

Melody,

Your right, that isn’t an easy read. Congratulations on making through it all!! The next post isn’t quite as tough to get through and is shorter.

Regarding the issue of extraordinary events, an ex-Mormon took issue with that over on a private FB group. He didn’t seem to have read the arguement very closely. Another person conflated facts with conclusions and another brought up the Flying Spaghetti Monster. Good times…Oh well.

I want to express my appreciation for this series of blog posts and also weigh in your summary of scholarly consensus:

1. Pilate, the Procurator, sentenced Jesus of Nazareth to death by crucifixion

One of the most certain data we have, attested in non-Christian sources.

2. Jesus died

Undoubtedly, unless the Muslims or Marcionites are correct.

3. After His crucifixion, Jesus was buried in a tomb by a member of the Jewish Sanhedrin named Joseph of Arimathea.

We can’t be sure Joseph was a member of the Sanhedrin, but it is plausible. This account also matches what we know of Jewish burial practices and as a devout Jew Joseph’s motivations make sense (has to do with not defiling the land; he wouldn’t need to believe Jesus was the Messiah or anything, though it seems he was sympathetic. He had means and motive.

4. The discovery of Jesus’ empty tomb

This is where consensus starts breaking down further, since Paul doesn’t mention it, but it is multiply attested and is plausible. It is also significant that we have traditions bringing up the “stolen body” theory which presuppose the empty tomb (which is a different issue than the resurrection). I think Joseph told his servants to move the body as soon as the Sabbath was over.

5. On multiple occasions and under various circumstances, different individuals and groups of people experienced appearances of Jesus alive from the dead.

I think there were resurrection appearances, or more precisely, people believed they saw Jesus. Paul is the most reliable, since he tells us with his own words and his conversion is highly improbable. I think next in order is James (Paul tells us this and the gospels don’t say he followed Jesus during his life, Josephus talks about him, etc), and then Peter. The group visions I think were fabricated to bolster reliability.

6. The original disciples suddenly and sincerely believed that Jesus was risen from the dead despite their having every predisposition to the contrary.

Part A, yes. Part B, strongly disagree. Visions of the resurrected Jesus fit very well within the apocalyptic context of the Jesus movement. His followers liked the Pharisees 1) believed in a bodily resurrection and 2) interpreted the belief Jesus was resurrected as proof of the imminent coming Kingdom of God when God would fix the world.

Dear Jared,

Its obvious you are a well read, intelligent gentlemen. We can’t prove positive things from a negative. Yes, the Marcionites did believe the visions of Christ’s resurrection were fabricated. The Ebonites have been proven to be Gnostics in recent Jewish scholarship and Nazarenes of Acts 24-26 believed the reports according to the letter of Ephaniaus. Eusibius believed the reports to be accurate as well. The Muslim tradition would not have taken hold for another five centuries. So their claims cannot be used as a patristic witness. Therefore, the bottom line is “who has believed our report?” Witnesses were still alive during Paul’s ministry in Corinth in AD 55. Apocraphal witnesses from Clement, a local pastor, claimed Jesus was seen in the resurrected form. John certainly echoed the thought that the saints should go to their deaths if necessary for this testimony. This hardly sounds like the wrong tomb theory in my book because the Centurian would have been brought before Pilate and executed for loosing the body or decimated a burial plot. And with 300 centurians possibly being in the vicinity, this is highly unlikely.

Today a handful of scholars such as Bart Ehrman, Karen King and Elaine Pagels attempt to lump the Gospels with second century Gnostic traditions through the fifth so called Gospel of Thomas. The Gnostics denied the embodiment of the Messiah and reality as we understand it. That is hardly a match for New Testament Jewish Gospel readings.

Thanks Jared again for the critique. Your last point is an interesting one. As you know, one of the hypotheses regarding the post-mortem appearances of Jesus is that it was only a vison of Jesus. Within Mormonism, we don’t nuance that word like other Christian traditions do. From my readings, theologians differentiate a vision from an actual appearance; a vision being something that doesn’t actually occur in time and space and thus cannot be seen by others except for the one having the vision, while an appearance (like the resurrection) actually occurs in time and space and thus can be seen by multiple people.

The argument I proposed was that, what the apostles and others had, was not a vision, but an actual appearance of Jesus in his resurrected body. This would be something unexpected as, within Jewish thought, the resurrection came at the end-times.

What you are saying gets around that argument. What you are saying is that a resurrection appearance would not be completly out of left field as it was a sign of the end-times. Did I interpret you correctly?

[Conversation migrated from facebook at your request]

Concerning the lottery analogy, your latest change didn’t actually fix it at all. You merely substituted a random person for a random number. The exact same flaw persists.

We are NOT asking the news anchors to PREDICT the winner. We are only asking them to accurately report the winner after the drawing.

Since you didn’t specify the rules of the lottery, lets use the simple example of a raffle where all tickets are put in a huge bowl, randomly shuffled and then drawn.

N = number of people in lottery.

C = chance of news reporter to accurately relay the name to public

The odds of any specific person winning is 1 / N.

The odds of someone winning is the sum of the odds of all individuals winning or N * (1 / N) = N / N = 1.

The chance of SOMEONE winning is 100% and the number of people in the lottery doesn’t matter. 10 people or 10 trillion people, it doesn’t matter because they cancel out.

So the final odds of the news reporter reporting accurately has NOTHING to do with how big the lottery is.

For most news stations this would probably be 99.9%, but if it was Fox news, then we can probably all agree it would be much lower.

Kris,

I concede to what you are saying. I don’t want you to think I’m being duplicitous. What I am trying to do is use an anology to explain a difficult concept of which probability theorists speak. I have found that with a blog like this, if I get too deep into philosophy or statistics, people just won’t read the posts. So, I have to find a simple way to explain stuff that won’t put people asleep.

Thanks for the push-back. I have to sit back down at the drawing board and come up with a better analogy. And thanks for taking the time to take my arguments seriously enough to actually engage with them.

mike

p.s. Thanks for bringing the coversation over here.

In the lottery example, maybe if you were saying that the odds of winning are so long that if a random person came up to you and told you that they won it then you would never believe them with Hume’s logic. (I would agree that you probably wouldn’t believe someone won a 300 million lottery unless they provided more evidence beyond personal testimony, even though you know that winning is possible.)

The tropical ice example has some potential. In that case, I think many of us would agree that if you live in the tropics and only have a few peoples personal testimony to the existence of ice then you probably should not believe in it, even though it is true. If you had multiple witnesses that were verifiably independent then enough of them could reasonably convince you about it’s existence.

Not sure why I’m helping you, since I’m an atheist, but you’re so polite, and as long as you are committed to the truth then we are on the same journey.

Kris,

I am going to write a post, “How to Win Atheist Friends and Influence Atheist People.” Ha. Man, I just cracked myself up.

I like where you are pointed with the lottery analogy. The only lacuna is that it doesn’t deal with the testimony of a witness. It jumps right over the witness and now we are dealing with the person that was involved directly with the event.

I think I may have come up with a better analogy in my discussion with my brother’s father-in-law, Brent. See the conversation below and tell me what you think.

Thans for the help

mike

The lottery situation you described to Brent seems reasonable, but it doesn’t seem to undermine the idea of proportional evidence.

The idea of proportional evidence is pretty solid. Extraordinary events require extraordinary evidence. When we move from common events to rare and then extremely rare events, you require a proportionally larger amount of evidence to warrant belief. When you move from an extremely rare event that we know is physically possible to an event that not only has never been demonstrated but which is physically impossible based upon our current understandings, then the likelihood of the event decreases dramatically, and the amount of evidence we need to justify belief increases dramatically as well.

Several times in history we HAVE documented natural events which changed our understanding of the universe, but in each example they required extensive and independently repeatable evidence to verify them.

Your bigger problem is that if you lower the bar on evidence required for belief in extraordinary events in order to justify a rational belief in the resurrection of Jesus, then the exact same logic will allow all manner of mutally contradictory supernatural claims in other religions to be viewed as believable as well.

Let’s look at the hypothetical example of the people who live in the tropics and, therefore, have no concept of arctic ice. For some reason, the writer ignores the obvious resolution: evidence for the existence of ice (blocks of ice, photographs, verbal descriptions, etc.) could be brought back for verification, evidence that would confirm the existence of ice. Sure, those who didn’t themselves go would have to depend upon the witnesses’ testimonies and the physical evidence provided, but as such they would have good reason to accept the concept of arctic ice. Having never been to the moon, I must accept the word of the astronauts who actually went there and evaluate the evidence (photographs of the moon’s surface and the actual moon rocks) they brought back. With such evidence I learn that the mineral composition of at least part of the moon is similar to that of the earth.

As far as the lottery example goes, there’s nothing extraordinary about lotteries or the people who win them. The fact is that many people have won many lotteries. It might be highly improbable that you will win one, but someone almost always wins. Just because the odds against winning are astronomical doesn’t negate the fact that somebody will win. And winners can be verified.

On the other hand, a resurrection would indeed be an extraordinary event. Is it possible that an individual (Jesus and putatively others at Jerusalem) returned from the dead? Yes. Is it probable? No, especially in light of the fact that no evidence exists that warrants belief in, let alone confirms, the reality of such an event. We have instead only testimonies to this alleged phenomenon, testimonies from the far distant past. Other than what’s contained in the Bible, there is scant historical record of Jesus having ever existed. As such, then reasonably and logically, one must conclude that there was no miracle of the resurrection in spite of the fact that one would like it to be otherwise.

Brent,

I think your overarching argument speaks to the imperfect nature of any analogy. Like I told Kris, I am attempting to give a simple analogy to explain a complicated concept of which probability theorists speak. However, your counterargument to my analogy of someone from the topics visiting the polar ice-cap is problematic, for it is an ad-hoc argument.

You said:

“…evidence for the existence of ice (blocks of ice, photographs, verbal descriptions, etc.) could be brought back for verification, evidence that would confirm the existence of ice. …”

You have added details to the analogy that aren’t part of the original analogy in order to strengthen your argument. You have presented a text book example of an ad-hoc argument. You could have said the following instead:

“What if the man from the tropics went with a camera crew from Discovery Channel? Then all the people from his local village could watch him as he explored the arctic ice, since they all have cable T.V.”

Regarding the lottery example you said:

“…there’s nothing extraordinary about lotteries or the people who win them. The fact is that many people have won many lotteries. It might be highly improbable that you will win one, but someone almost always wins. Just because the odds against winning are astronomical doesn’t negate the fact that somebody will win. And winners can be verified…”

I’ve been re-thinking the analogy for the past few days. Once again, like I said to Kris, I concede that the analogy is problematic. Kris got me pointed in the right direction and you have helped me to revise my analogy further.

It is true that a winning number will be picked. That is 100% certain. It is not 100% certain that the winning number will actually produce a winner. That is the reason power-ball goes on and on and on….with a larger and larger money pot to be won, but someone (as you pointed out) will eventually win. As you said, it is highly unlikely that I will win the lottery. It is a highly improbable event that I, Mike Barker, will win the lottery. I don’t win the lottery all the time. Someone does, but I don’t. So the question is, why believe the evening news when it says I won the lottery? The answer is in asking the question, what is the likelihood of the evidence of me winning (the report from the evening news), if I had not won? That likelihood is very low, so we should believe the evening news’ report regarding me winning the lottery.

Regarding the resurrection of Jesus of Nazareth, you said:

“…We have instead only testimonies to this alleged phenomenon, testimonies from the far distant past. Other than what’s contained in the Bible, there is scant historical record of Jesus having ever existed. As such, then reasonably and logically, one must conclude that there was no miracle of the resurrection in spite of the fact that one would like it to be otherwise…”

This appears to be an argument against the historicity of the Bible. For that I refer you to the above conversation between Jared Anderson (Jared is finishing his Ph.D. in Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, focusing on the Gospels and New Testament) and Dr. Tom Roberts ( Ph.D. in Theology from the Hellenic Orthodox University in Athens, Greece)