In anticipation of Easter, the next few posts will be looking at the various hypotheses that scholars have developed to explain the resurrection and Jesus’ post-mortem appearances. Using historical critical methods, we will then decide which hypothesis best explains the material we have in the New Testament. This is Part I, of what is presently, a seven-part post. I say “presently” because, as it stands right now, the entire post is over 60 pages long – double spaced; it might end up getting broken up into more parts. Part I will only present the different hypotheses and the history behind them. It will not be an attempt to provide any type of criticism.

I love the following quote:

“You need to raise the level of discourse. One of the things that our culture tends to do is it tends to dumb down things. Our culture is impatient with having to study. It’s impatient with having to do critical thinking. It’s just, “Give it to me, give it to me, fast, quick, quick, quick! And I want it simple.” Keep it simple stupid is the principal; the KISS principal you know. I say what we need to do is…. we don’t need to water down the substance of the discourse. We need to boil up the people. If they’re going to be educated in all kinds of other fields, why should they not be educated about their faith? You see?…..

“I think that it is the task, the educational , the pedagogical task of the church to raise up the level of discourse about their own faith to the general level of discourse on any other intelligent subject that the culture is going to be prepared to talk about. And I would say it is the obligation of any thinking Christian to be able to articulate their faith at a level of discourse that could challenge the basic cultural assumptions.” (Dr. Ben Witherington, III, Professor of New Testament, Asbury Theological Seminary – Black Hawk Sermons; The Da Vinci Code – A Look at the Historical Accuracy. Pod Cast 1:14:49)

A SURVEY & CRITIQUE OF THE DIFFERENT RESURRECTION HYPOTHESES: PART I

Literal Historical Event Theory

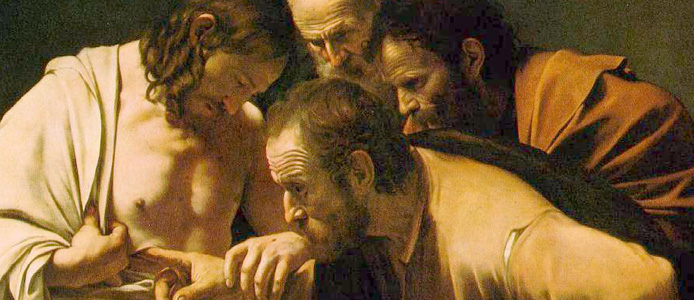

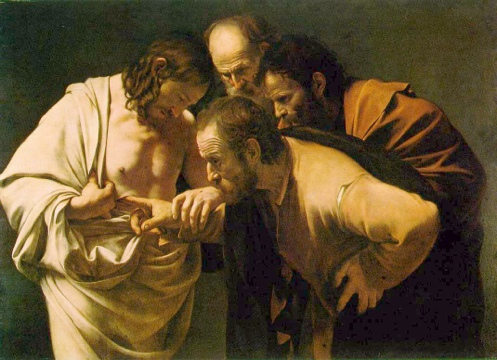

This was the view that the early Church Fathers had. That is to say, the body of Jesus Of Nazareth that was crucified and and laid in the tomb actually was raised again to new life and then taken into heaven by God. Early Church Fathers like Terturlian had a very strong emphasis on the resurrection of the flesh; that Christ didn’t just rise in a sort of “spiritual way”, but that it was His flesh that rose again from the dead and which He carried with him into heaven when He ascended. Any atempt to have a gnostic view of the resurrection of Christ, which would depreciate the value of the human body, or of the material (in favor of the spiritual) was reputiated. Rather, they affirmed the value of the material and the fleshly and the corporeal. This was done by saying that Christ was literally raised with His human body and carried it with Him into heaven.

Conspiracy Theory

This is the earliest counter-explanation of the resurrection of Jesus. This theory is actually found in Matthew 28:13. Here the Jews told the guards, “Say ye, His disciples came by night, and stole him away while we slept.” This theory was resuscitated in the 18th century by European Deists. Deists were theists who believed in a creator God of the universe, who is the source of moral law and to whom we have moral obligations, but who has not revealed Himself specially in any particular religion – such as Christianity or Islam or Judaism. Therefore the deists didn’t believe in the reality of miracles, of God’s intervention in history. The deist god has often been compared to the clock-maker god who made the clock in the beginning, designed it, wound it up and then set it ticking and then did not tinker with the mechanism thereafter; didn’t interfere to adjust the clock in any way. Therefore, miracles, like the resurrection of Jesus, do not occur.

A good example of this perspective is Hermann Samuel Reimarus. Reimarus was an 18th century German Christian who began to have severe doubts about his faith. He eventually wrote a massive manuscript in which he discussed his different doubts including his doubts about the resurrection of Jesus Christ. He proposed that the resurrection was actually a conspiracy engineered by His earliest disciples. The disciples had enjoyed an easy life of preaching with Jesus; traveling about, teaching people. So, in order to continue this lifestyle, they stole the body of Jesus out of the tomb and then lied to people saying that Jesus had risen from the dead. This was done so that the cause of Christ and their role as Apostles of Christ could continue. Reimaurs never published his book. Gotthold Ephraim Lessing managed to get a hold of the manuscript. Lessing was a librarian in Ducal Library at Wolfenbuttal, Germany. He claimed to have found the manuscripts in Ducal Library and began publishing Reimarus’ work as “Fragments by an Anonymous Writer” (Wolfenbütteler Fragmente(1774–1778), giving rise to what is known as the Fragmentenstreit). These fragments of, “an Anonymous Writer,” caused a storm of controversy in Germany because of its attack upon the resurrection of Jesus. This basically initiated this conspiracy theory which was then adopted by other continental and English deists as well; basically treating the resurrection of Jesus as a hoax that was engineered by his disciples.

The Apparent Death Theory (Swoon Theory)

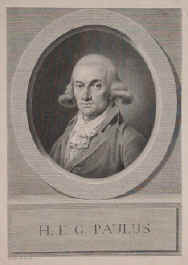

Towards the end of the 18th century another theory began to appear. This was the apparent death theory. This theory was defended by people like Heinrich Paulus and the so called father of modern theology, Friedrich Schleiermaacher. Paulus was a champion of what has been called, “the natural explanation school of Biblical interpretation.” That is to say, he accepted the letter of the Biblical text in what it said. He would then provide natural explanations for these events. This allowed the events to occur without needing to be as miraculous. An example would be that Jesus’ feeding the 5,000 with the fish and loaves was done because there was a cave filled with bread and fish. The disciples were inside of the cave and then handed the food out to Jesus and then he handed it out to the crowds. Another example would be Jesus walking on water. This is was achieved by a floating wood platform just under the surface of the water. He would then just walk on this platform and it appeared he was walking on water.

Similarly, Paulus thought the resurrection could be explained by saying Jesus really didn’t die on the cross, but He had merely swooned (fell unconscious). He was then later revived in the tomb. Coming out of the tomb, He appeared to His disciples who thought He had resurrected from the dead. These Apparent Death Theories can become very elaborate. Some claimed that Luke, the physician, was in on the conspiracy. Luke had administered medicine to Jesus that would dull the pain and make Him pass out. Luke then helped revive Him in the tomb. Some claimed the possibility of a secret society, possibly the Essenes, who engineered the apparent death. Sometimes Jesus was in on the conspiracy allowing Him to perpetuate the notion that He was the Messiah.

Schleiermaacher actually adopted the Apparent Death Theory himself. The resurrection of Jesus was just an apparent death. Schleiermaacher would say the Jesus only appeared to be dead. Somehow there was still this glimmer of life in Him. With the coolness of the tomb and electrical activity from the storms going on, this somehow re-energized Jesus’ body. After Jesus was revived, He came out of the tomb and convinced everyone that He had risen from the dead. As you might imagine, the Apparent Death/Swoon hypothesis didn’t last too long.

The Mythology Theory

In 1835, just after Schleirmaacher had published his own work, David Friedrich Strauss came out with a book that was really pivotal in the history of theology and historical Jesus study called, “The Life of Jesus, Critically Examined.” It was an absolute watershed in the history of theological thought about who Jesus was. Strauss rejected both the conspiracy theory of Reimarus as absurd and concocted; that no great religious movement had ever been based on lying and deceit; it is obvious that its adherents sincerely believed the truth of what they proclaimed; it would be absurd to suggest that the disciples were hoaxers and conspirators. Neither did he find plausible the apparent death theory of Paulus. He said that the contorted and ad-hoc explanations that Paulus came up with was utterly implausible. In particular, he said that a half dead Jesus who crept out of the tomb, desperately in need of bandaging and medical attention would never have elicited, in the disciples, the belief the He was the conquerer of death and the Prince of Life – rather than someone who had just managed to escape the conquerer. Neither the conspiracy theory nor the apparent death theory was credible to Strauss, but this didn’t mean that Strauss was ready to adopt the literal view of the church fathers. Rather, under the explicit influence of David Hume, (Strauss mentions Hume by name) Strauss was convinced that you could not deposit miraculous explanations of historical events; another explanation would always be more probable. Under the influence of Hume, Strauss proposed the theory of myths.

This basically said that there was a considerable length of time in between the crucifixion and the eventual compilation of the gospels. Strauss tried to move the gospels back as far as he could from the events of the crucifixion – to push their composition into the 2nd century. This would allow a window of opportunity in which the stories about Jesus could be told and re-told and over-layed with mythology until the rabbi from Nazareth was transformed into the divine Son of God risen from the dead. Stories like the empty tomb and its discover, stories about Jesus’ appearances after His death are all legends. They are legends and stories shaped by mythology that arose decades after Jesus was gone and buried and don’t represent the historical facts about what actually happened which are now very difficult to recover. Strauss’ Myth Theory became the dominant view among New Testament scholars during the first part of the 20th century. It was pretty much the same view that was adopted by Rudolf Bultmann who was one of the most influential New Testament scholars during the 20th century. Bultmann believed that the resurrection of Jesus is basically a myth and what we need to do is “demythologize” it. We need to strip away the mythology to see what its [ the resurrection] real significance is. Strauss did the same thing. Strauss appealed to Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel’s philosophy, the German idealist. This was done to find the real message of Christ. What Strauss said was that the incarnation and reurrection of Christ is really a kind of metaphorical expression of Hegel’s view that the infinite and finite are one. That the infinite (the absolute or God) unfolds in the finite (material)world and the material universe. The finite just becomes an expression of the infinite. It is a kind of pantheism.

Bultman was not an idealist, instead he turned to Martin Heidegger, the existentialist (you always turn to the philosophers that are contemporanious with you to find the truth behind the myth of Christ and the resurrection). Existentialist philosophy was atheistic and so for Bultman, the resurrection had no different meaning than the cross of Christ – which was simply that life will end with death and that we can live authentic lives in the face of death and our own finite existence. That was the truth behind the resurrection. Which was mythologically expressed in the scriptures by the notion that Jesus died and was raised from the dead.

Subjective Vision Theory

Strauss could not deny that the original disciples saw or had experiences of seeing Jesus alive from the dead. Even though he could push the gospels out into the 2nd century, he couldn’t do that with the letters of Paul. Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians in chapter 15, lists the witnesses of the risen Christ. So Strauss had to appeal to hallucinations; that the disciples had simply hallucinated. That became the center piece of the Subjective Vision Theory on the part of scholars like Emanuel Hirsch and, then more recently,Gerd Lüdemann. This view says that the disciples had these visions of seeing Jesus alive after His death. These visions were not actual sightings of Jesus; these were subjective. That is to say, they were projections of the disciples’ own consciousness of their own minds. Lüdemann, for example, believes that Peter was emotionally distraught for having denied Jesus three times and he was consumed with guilt, because he had let his Lord down and denied Jesus. As a psychological release, Peter projected visions of Jesus alive after His death and this gave him [Peter] a sort of catharsis and release from his guilt. Lüdemann doesn’t like the word hallucinate, he prefers the phrase “Subjective Visions.” Hallucinations sounds too demeaning. He wants to say these are religious visions which are profoundly important and significant on the part of those who had them. This, of course, started a chain reaction among Jesus’ disciples and they began to hallucinate.

You might say, “What about Paul?” Paul wasnt’ in the chain because he was a persecutor of the early church. He was a Jewish Pharisee that was ravaging the church. What about him? What about his experience?” Paul was laboring under a secret guilt complex, that he wasn’t even aware of, because he couldn’t live up to the demands of the Jewish Law. He was zealous for the Jewish Law but couldn’t live up to it and so he felt guilty as a Jew and his zeal to persecute Christianity was merely an expression of over compensation for a secret attraction he felt for Christianity. Finally on the road to Damascus, this subconscious attraction burst into consciousness and projected this vision of Jesus on the Damascus road leading to Paul’s conversion. The empty tomb story is a later legend that has no credibility and arose years later as an explanation of what happened to the body. But the resurrection originated in these subjective visions on the part of the disciples.

The Objective Vision Theory

This is a more sympathetic view which has been defended by Hans Grass and Wolfhart Pannenberg. The idea of an objective vision might sound like an oxymoron at first. How can you have an objective vision? A vision isn’t something that is objective, it is something that occurs in your mind. What Grass and Pannenberg believed was that God caused the disciples to see these visions of Jesus. They were actually seeing Jesus. They weren’t self-induced hallucinations. They weren’t projections from their own minds in the way Lüdemann thinks. Rather God caused the disciples to have these visions of Jesus. an analogy of this is, at times people will have what are called “veridical visions.” A veridical vision is a vision which is accurate. It really is a vision in which you see something. For example, God may cause me right now to have a vision of my brother, wherever he is; maybe sitting in his office at home or at church, etc and it would be accurate. This would be a veridical vision. Pannenberg and Grass say what the disciples had were veridical visions caused by God. They were not in the external world. Therefore they dismiss as legendary the physicality of the appearances. Jesus didn’t really give the disciples fish to eat. They didn’t really touch His body. He wasn’t really physically present. It was just a visionary seeing. It wasn’t a hallucination. It was a veridical vision. They were seeing Jesus in glory as it were. Therefore Grass doesn’t believe in the empty tomb. According to Grass the empty tomb is a legend and the resurrection of Jesus is just the seeing of Jesus in His spiritual body. Pannenberg differs from Grass in that he does affirm the empty tomb. Pannenberg believes the body of Jesus was raised from the dead, the tomb being left empty as a result. Pannenberg doesn’t believe the physical resurrection appearances. He thinks the body was somehow dematerialized or something and later the disciples experienced these objective visions.

The Interpretation Theory

This is a view of the resurrection that has been promoted by certain contemporary theologians like the Episcopal Bishop, John Shelby Spong. Basically what this view says is that after Jesus’ crucifixion, His disciples had some sort of profound experience of Jesus; something that radically altered their lives. But, we cannot say what that experience was. Indeed the disciples themselves were at a loss of words to describe what this experience was; of Christ’s presence and forgiveness. And so for want of a better interpretive category for this, the disciples latched onto the Jewish category of resurrection from the dead. Thus they said, “He is risen from the dead. ” That was a means of expressing this sort of mystical experience they had of Christ after His death. So it wasn’t intended to be literal. It wasn’t intended to mean that the body got up out of the tomb and was alive again. Rather it was just an interpretive category borrowed from Judaism to describe their mystical experience of Christ.

Spong relates this to Peter’s denial of Christ. He says that Peter had denied Jesus three times, just at the time when Jesus needed him most, and this is after Peter had sworn allegiance to Jesus even unto death; then Peter failed Jesus. So Peter went back to Galilee, burdened with guilt and mental anguish for having denied Jesus. Peter couldn’t reconcile this in his mind. Here he had believed Jesus was the Messiah, that Jesus was the one anointed and promised by God and here, Jesus was now dead. This just didn’t make sense to Peter. As a means of alleviating the sort of guilt complex that he [Peter] wrestled with, he had this experience with Jesus and began to see that Jesus had forgiven him for his betrayal. In order to describe this experience, Peter said, “He is risen from the dead!” The other disciples also began to adopt this metaphorical language of being risen from the dead. That is how the belief in Jesus’ resurrection originated as as sort of interpretive category fro the experience of Peter.

Next week we will begin to look at critiques of three of the hypotheses.

I would like to present an opposing view to this view of Peter and his denial of the Lord: ” Lüdemann, for example, believes that Peter was emotionally distraught for having denied Jesus three times and he was consumed with guilt, because he had let his Lord down and denied Jesus.”

The following is taken from Gerald N. Lund’s book “The Kingdom and the Crown: volume 3 Behold the Man”. It is the chapter note for Chapter 31 found on pages 525-527

“A word about Peter’s denial is in order. Almost universally, commentators attribute Peter’s denial to cowardice. Some have even referred to it as a shameful lapse of character. They grudgingly note that he later repented and went on to become a strong and effective leader, but only when he overcame this “flaw” in his character.

“It is true that on the surface, the record of Peter’s thrice-repeated denial might suggest that. However, depicting Peter as a panic-stricken, trembling coward who slinks away at the first threat of danger doesn’t square with the rest of the picture. Did he simply buckle under the tremendous pressure of that night? Is it simply that when the chips were down, he couldn’t take it and scrambled away in an effort to save himself?

Think for a moment of what had happened just hours before in the Garden of Gethsemane. When Judas led the soldiers to the Savior, he didn’t go alone. Both Matthew and Mark tell us that he brought a “great multitude” and that they were armed with “swords and staves” (Matthew 26:47; Mark 14:43) What did Peter do when he saw this very real and dangerous threat—a much more direct threat than was presented to him in the courtyard? Did he bolt and run? Did he slither away into the darkness? No. Of all the apostles, he alone sprang into action. He whipped out his sword and waded in swinging. Malchus lost his ear that night. To a craven coward? The idea is ridiculous. Peter stopped only when the Lord himself told him to put away his sword. Yet these commentators would have us believe that just hours later, he is paralyzed with fear. It just doesn’t add up.

“Or consider this. Matthew tells us that after Jesus was arrested, the rest of the twelve “forsook him, and fled” (Matthew 26:56). But Peter and John followed after Jesus, even though he was under armed guard. That surely wasn’t the safer course of action. If Peter was so petrified with fright, as some would have us believe, why would he go inside the courtyard at all? Why not just stay away and hope things would work out?

“Yes, Peter did three times deny knowing Christ. There is no doubt of that. Yes, he did weep bitterly over his denials. But should we not be a little cautious about imputing motive and metal state to Peter when the Gospel writers themselves do not do so?

“There is another possibility we should consider. Several months before, when Jesus had told the apostles of his approaching death, Peter tried to dissuade him from that course. In a stinging rebuke, Jesus chastised Peter for what he was trying to do. (see Matthew 16:21-23). Then, just hours before the three-fold denial, Peter took up the sword in Jesus’ defense. Was Jesus pleased with this show of courage? No. Again Peter was rebuked and was specifically commanded to stop interfering. Did not Jesus tell Peter that if he needed help, he could call down twelve legions of angels? Isn’t it possible that Peter backed down that night, not because of fright, but through reluctant obedience to what was clearly the Master’s will?

“True, it does say that after the third denial Jesus turned and looked on him and then Peter went out and wept bitterly. (Luke 22:61-62). ‘Isn’t that proof of his shame and remorse,’ some would say? But why must we assume that the look Jesus gave Peter was one of condemnation? The scriptural record gives no such description. Perhaps Jesus looked at his apostle with approval. Perhaps it was his way of acknowledging that Peter was doing what he wanted him to do. Wouldn’t Peter weep just as bitterly knowing that Jesus was going to die and that he was prevented from doing anything to try to stop it?

The author is not taking the position that these possibilities are what really happened, only that there may be other explanations for the denials than fear and cowardice. If Peter turned coward that night, it was a strange contradiction in his character. Let us not rush to judgment based on a limited account of what happened that night. If they do not, perhaps we too should be a little more cautious before doing so.”

Chareine, I’ve tended to lean towards this explanation as well. I would agree that neither this explanation nor the more commonly accepted version of cowardice is 100% explicit from the text, I would say that both ways of interpreting the events could be supported. But I choose to look at it the way you have described.

Compelling. Thanks for posting.

“We need to boil up the people. If they’re going to be educated in all kinds of other fields, why should they not be educated about their faith? . . .” Ouch. Good point. Now go away and leave me alone.

Also: What an amazing undertaking. And I’m looking forward to what follows. . . wonderful addition to my usual Easter meditations.

That is one of my favorite quotes and it comes from an Evangelical scholar. Parts I – III we posted last year and then stopped because no one was reading them. We thought that now with a larger audience, it might get some traction. I will be using these posts as the basis for this months’ lessons for my Priest’s Quorum; they love this kind of stuff.

I like Gerald Lund’s view

. It makes perfect sence to me