In the summer of 1865 the First Presidency issued a statement in the Deseret News condemning certain theological writings they considered to be so objectionable that they ordered copies of the works to be destroyed. The volumes in question had been written by Orson Pratt, a member of the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles, and noted belligerent of Brigham Young. Pratt had attempted — and failed — to systematize Mormon theology into a coherent strategy. Absent at the time on a mission to Austria and Great Britain, he had no option but to offer a written apology, printed in the Deseret News. Offering his “most sincere regrets”, he lamented;

“I learn that many of my writings are not approbated; and it is considered wisdom for them to be suppressed. Anything that I have written that is erroneous, the sooner it be destroyed the better, both for me and the people; for truth is our motto, and eternal truth alone will stand.”

Pratt’s venture would not be the last time a senior church leader would find First Presidency disfavor in attempting to publish Mormon theology. Three years before his death, and having published several volumes of Church history and theology, Seventy and Assistant Church Historian B. H. Roberts prepared publication of his major theological treatise “The Truth, The Way, The Life”. However, a public dispute arose between Roberts, a partial-evolutionist, and Joseph Fielding Smith, a staunch young-earth creationist. In the wake of the disagreement, Roberts’ book did not find support in church publishing, and would not reach the press for more than sixty years.

Thirty years after Roberts’ attempt, Joseph Fielding Smith found himself embroiled in a fresh controversy surrounding the publication of another Mormon theological work. Smith’s son-in-law and young Seventy Bruce R. McConkie had succeeded in publishing — apparently without Smith’s knowledge — what would become the chief Mormon systematic theological work of the twentieth century, Mormon Doctrine. President David O. Mckay called for an inquiry headed by his counsellor in the First Presidency J. Rueben Clark. Clark’s report conceded that the book filled a need, but that the use of declarative language and forthright statements on matters that consisted of little more than personal speculation, added with several notable errors, rendered the book indefensible as an authoritative Church publication. As President of the Twelve, it fell to Joseph Fielding Smith to talk to his son-in-law McConkie about the First Presidency’s decision to halt publication. Eventually, Covenant Publishing were forced to include a statement in the much-edited second edition admitting that the work was not authoritative and did not necessarily reflect the views of the Church.

What may have contributed to the strength of feeling against McConkie’s work was his choice of the word ‘doctrine’ in the title. While theology is simply the study of God (in much the same way as biology is the study of living things), doctrine is derived from the Latin doctrina, meaning ‘teaching’, implying an authoritative view of the church. In Catholicism, theology does not require an action of the Magisterium — the authority that determines the authentic teaching of the church. Theology can be done by ordinary theologians or, for that matter, by ordinary members of the faithful. However, doctrine must be sanctioned by the Magisterium, and thus cannot be determined by anyone other than the combined body of the Pope and the bishops who are in communion with him.

Theology can be broken down into two broad fields: Scriptural theology, and systematized theology. Scriptural theology is a manner of arranging and understanding God’s revealed word through history, following the narrative flow of the scriptures, the redemptive history of humanity. Systematised theology is a method of studying without reference to chronology, but thematically. We experience something like scriptural theology in seminary and institute classes, in which the flow of the sacred text is followed, while we experience systematic theology when we open the Bible Dictionary in the LDS edition of the Bible.

The scriptures are full of teachings, those implied in narrative and parable, and those explicit in commandment and rebuke. The central theological question becomes: what for the faithful remains continuously true through varying generations and cultures?

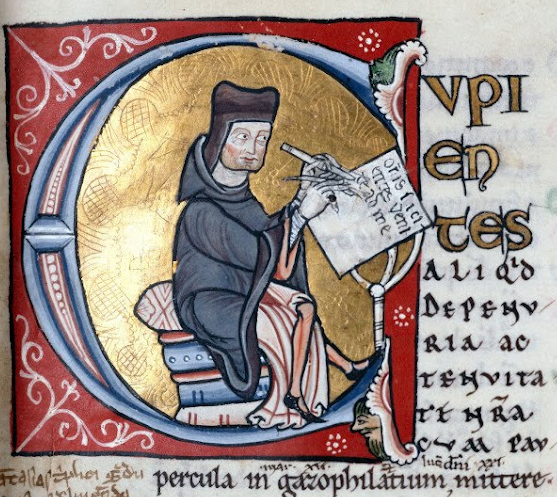

In world religious practice, theories of interpretation (hermeneutics) are generally posited by groups of sages in scriptural schools or monasteries, distilled over centuries of editing and reworking by successive students. In Christianity we have the several SummaTheologica of the Church Fathers including Aquinas, Ockham, and Peter Lombard. Interpretations of scriptural texts are explored in seminaries and colleges, the Rabbinic schools and by the tannaim, the centres of vedic interpretation in the Hindu mīmāṃsā, and in the work of the Islamic mufassirun. In each branch of religious observance, the relevance, durability, and coherence of a doctrine is shown by its fruitfulness, by its widespread application, its relation to other cherished ideals, its agreeableness with religious authority and lay member alike, and by the power of its homiletic persuasiveness. In this process of filtration, spiritual consideration, and intellectual graft, doctrine bubbles up to the surface of the religious imagination while other, less coherent teachings simply fade into the depths of the rabbinic archive, perhaps to be rediscovered at a more appropriate time.

Typically, systematized theology is produced by a successive professional class of clergy, who are authorities by virtue of their years of scholarship. In those religions with a lay clergy, for example Quakerism, the theology is distinctly variable according to the local society and how it feels moved upon by the power of faith and the priesthood of the believers. At times an influential member may prevail upon others; in the late nineteenth century, Edward Newman attempted to persuade other Quakers that a theory of evolution was contrary to the central biblical idea of God as creator. However, some Quakers felt moved to accept Darwin’s theory, and had the intellectual freedom to do so.

In some senses Mormonism is a hybrid faith system in which a lay unscholarly clergy administers doctrine to a membership all of whom also understanding themselves to be theologians in their own right, but who must yield to the greater authority of higher priesthood, despite the possibility of personal inspiration or individual scholarly acumen being at odds with centralized teaching or practice. In addition, the claim to ongoing revelation means that the central leadership cannot be wrong — they are led by God, and have persuaded the faithful that they cannot lead the people astray. This makes the evolution of a Mormon systematized theology practically impossible; while the lay leadership is ill-equipped for the task, and cannot venture into speculation, specialists in hermeneutics or interpretive theory are not intellectually free to apply their craft. The result is to produce a homogenized and simplified theological framework — one that is detailed enough to comply with broad scriptural injunction, but open enough to allow for some measure of personal interpretation and inspiration by local leadership or members themselves.

In addition to this balancing act, postmodern views on how texts operate offers a further challenge. A central activity of any theologian is to determine what scripture means. In the past, critical practice places an author of a text as the ultimate authority of meaning (author and authority share similar etymological roots). Thus, the project of a scriptorian or reader could quite easily be understood to involve trying to determine what the author meant when he wrote the text, the meaning of a scripture being a fixed thing which requires discovery. However, since the text itself assumes a life beyond the author, and since the text can come to mean different things to different people, times, and cultures, one could legitimately claim that a given text assumes a variety of meanings, depending upon who is reading it, beyond the possible intended meaning in the mind of the author. In some ways a text is a reflective device showing a reading audience many of their own frailties, hopes, desires, and characteristics. This is what Roland Barthes referred to in 1967 as ‘the death of the author’. In this sense, the author passes on his or her text to a future and unforeseeable reader who will find meaning far beyond (and sometimes at odds with) authorial intention. Thus, to modern practitioners, a text has no fixed meaning, and readers need to employ interpretive techniques that reveal personal significances.

It would not be surprising to find such literary theories to be shunned by mainstream traditional religious thinkers who perceive written scripture as the revealed word of God, and for whom there is little room for interpretive flexibility. Some exceptions are beginning to emerge: The Roman Catholic theologian Thomas Guarino has recently responded to the challenge of postmodern critical theory in his book Foundations of Systematic Theology (2005). For him, while the love story of God’s passion, the ‘salvific dialogue’ of scripture, has become ‘crystallized’ in creeds and doctrines, the aim of systematic theology is to employ philosophy, of the nature of truth, of hermeneutical theory, of predication of language, and of mutual correlation in order avoid rendering the faith as ‘less intelligible, less attractive, or into a radically changed form.’ To illustrate his point, Guarino cites Irenaeus, who wrote of the perfect house of faith, the removing of a beam of which would cause the house to sag. The main emphasis of modern theology is that it must reclaim some philosophical ground. Guarino does this largely by countering the problems of postmodernism by employing Hans-Georg Gadamer’s response to the hermeneutic problem — which is to combine both historically-charged meaning with reader response — a fusion of horizons where the scholar finds the ways that the text’s history engages with their own background as a reader. Thus, the teachings of the church may be differently and creatively re-expressed while maintaining a stable identity throughout history and culture. This argues for “unity within historicity, for identity within cultural difference. It allows for change and development because it calls for the importance, indeed necessity, of reconceptualisation while concomitantly maintaining the fundamental stability of the dialogical narrative between God and humanity called revelation.” (p. 196).

The central question comes to this point: what for the faithful remains continuously true through varying generations and cultures? Religious hermeneutics must (according to Guarino) navigate the troubled waters between the Scylla of wooden repetition and the Charybdis of interpretive anarchism.

It would be difficult to imagine a theological writer such as Guarino working in a Mormon context. In Mormon thinking, interpretive practice must always be judged against the solid benchmarks of scripture, prophetic utterance, and the current methodology of the Church, ascerting these benchmarks to be solid fixed points. Any holes in scriptural interpretation can be plugged by the utterances of the central lay clergy, seconded by personal spiritual feeling. The rest is part of the heavenly mystery, to be revealed to humanity with clarity at the appropriate time. And yet the LDS Church has passed through several modes of responses to the call for theological clarity. At earlier times, members were considered to be on a more equal footing with leadership, encouraged to become theologians, scriptorians, and prophets for themselves. At times, top-down declarations have reprimanded wayward saints, ascerting boundaries to theological speculation. When the Church produced the Bible Dictionary as part of its edition of the Holy Bible, a systematized theology was produced as the result of the work of a team of nameless writers. At present theological statements are offered by an administrative class one must assume speaks with authority of the Brethren. However helpful such theology may be, such corporate statements will inevitably fall short of providing a full systematic theology, because the reserve of Mormon theological certainty is a shallow pool, one that shows no sign of expanding. What, for example, would a Mormon theology of sexuality look like? To what extent do ‘church standards’, norms, online statements on broad gospel topics, and talks by the clergy supplant a struggle at the grindstone of theology? To what extent do proclamations stave the hunger for a system of belief that adequately enunciates the beauty of a living faith? At least for those who have tried — and failed — to reach broad agreement in articulating a Mormon theology, and those in their thousands that have consumed these theological attempts, there is a space to be filled.

Kenneth Rexroth called theologians unstable philosophers. I think he was being charitable. I mean, really, at least philosophy (today) tries to grapple with reality.

I’m not clear on the point of your comment, Edwin. Were you simply coming to this post to belittle all theology, or was there some meaning more relevant to this post that I’m missing?

I’m hopeful that the information age is making the inability of the institutional church to control information, and consequently history and theology, a more obvious reality. I just hope that the result is ultimately one of greater inclusion and complexity rather than further entrenchment of unexamined platitudes. I trust it will be, but we have growing pains to look forward to, still.

Growing pains, and pains in certain backside regions for sure.

Yes. 🙂

What WOULD a theology of sexuality look like? Would the author not suggest any examples? What gaps are left unfilled (no pun intended)?

“There is a space to be filled.” Sure. But how large a space? How small? The article spends a great deal of word count explaining the difference between theologians and church leaders, and the need for literary critical theories’ when interpreting even sacred texts–a consideration so important that the author should consider writing a more accessible essay for less educated members–then falls flat with the final proposition. It feels cowardly or something to end with this vague understatement, without offering opinion as to the space’s breadth, or as to solutions. At the very least, it’s anti-climactic. What are the consequences of the space? Does it imply anything about the truthfulness of the church? This piece feels unfinished by at least a few sentences.

Thanks for your response. The aim of the article is to highlight the problems inherent in trying to construct a Mormon theology — of the problems of authority, revelation, and intellectual freedom. I am not a theologian, and could offer very little in this regard. However, you may be interested in the work of Adam Miller, Terryl Givens, Jim Faulconer and Blake Ostler who are — in my opinion — in the early stages of constructing a Mormon theology, in that they address theological concerns, but have yet to attract widespread response from leadership or members. Thus they are yet to achieve a fully-accepted systematic theology.

Blake Ostler’s series is one of the most ambitious attempts at Mormon theology. Adam Miller and Jim Faulconer have done some work in that area. All three of them speak to the place of theology in Mormonism in interesting ways, too.

Thanks for your comment. I could well have said something about the efforts of Adam Miller, Terryl Givens, Jim Faulconer and Blake Ostler. While their work (and that of Miller’s colleagues at the Mormon Theology Seminar) are of great interest, I felt that they are at an early stage, and have yet to attract a real response from general membership or leadership. They do not, for example, find their way into church materials or general discussions at this point, and have thus not had the same impact as a work by a serving authority of the church (Mormon Doctrine, Doctrines of Salvation, etc.) It remains unknown to what extent these theological offerings reflect Mormonism as understood and practiced by the church.

Oh and Terryl Givens’s forthcoming book from Oxford University Press is quite theological in approach too.

“The result is to produce a homogenized and simplified theological framework — one that is detailed enough to comply with broad scriptural injunction, but open enough to allow for some measure of personal interpretation and inspiration by local leadership or members themselves.”

I hope this framework leaves room for more inclusion and a more tolerant dialogue within the church, as Jonathan is suggesting might happen with the diminishing control over message that church leadership has.

This started out good, but became increasingly difficult to follow and veered away from Mormonism never to return.

Thank you for this great post! It hit on so many themes I've been pondering lately.

One of the more eye-opening results of my faith crisis was learning about and exploring the extensive theological landscape of the wider Christian tradition. I always knew about systematic theology, of course, but I think I was quick to dismiss it as philosophy or an unhealthy attempt to find answers to all possible questions within the doctrines of a particular church. Once I actually started looking into systematic theologies, I recognized that they were windows into the views and intellectual context of their author's era, and that they were extremely helpful and important in the health and growth of Christianity.

Like you intoned in your blog post, I don't think Mormonism is primed (yet) for that sort of intellectual deconstruction and dialog. I don't fault "the brethren" for this: I see them as the products of a lay clergy system, too, and expecting them to be theologians isn't fair.

(Almost done, promise!) I think the main reason I enjoyed your post, however, comes from my own searching through our history. Again, as part of my faith crisis, I felt like I was finally ready to give an honest analysis of Mormon "doctrine" and figure out if it was something I can live with if not believe. I was a little surprised, to be honest, as I read through primary documents from Joseph to the McConkie era to find that all of our major teachings have changed with time (radically, in some cases). I've focused so much on changes in the Joseph-Brigham-Taylor era that I missed out on all the changes that came later! In a recent discussion with a friend I expressed that I didn't think we really actually *have* doctrine in our tradition: we have beliefs and dogmas (which in modern church vernacular are referred to as "doctrines" and "policies"), but they seem to be interchangeable and malleable. What was "doctrine" to Joseph and Brigham has been labeled "policy" and discarded by McKay. At best we can mine the record for quotes from Joseph Smith (which always seems to be considered the ultimate authority), but even then we run the risk of cherry-picking. Joseph's thought evolved rapidly with time, and his own quotes aren't always consistent.

All of this was once very taxing to me. I felt the weight of having to organize and defend "doctrine" (against myself as much as anybody else). Now that my paradigm has shifted, the weight is gone, and like you I'm intrigued by the future. The information age is going to rock the Church, I have no doubt, and it'll be interesting to see whether or not theologians will find a role in the community that emerges.

Taylor, I wonder if you have any books or articles to recommend related to changes in the Joseph-Brigham-Taylor era? I have, for several years, been aware of doctrinal changes related to Adam-God, polygamy, Word of Wisdom, etc. but was still a bit unsettled by parts of Charles Harrell’s “This Is My Doctrine” when I read it earlier this year. I do think that the deconstruction of LDS doctrine can open up fascinating possibilities – and ultimately new revelation for the Church. It takes some paradigm shifting, but I personally find the clarity of an openended humility that this can bring illuminating.

“Specialists in… interpretive theory…”

Seriously? This isn’t a thing, fyi, except perhaps in the mind of a person with delusions of grandeur and no concept of credible academic scope. I’m not referring to you, but anyone who would deem themselves such a “specialist”.

You unduly put other faiths on a theological pedestal, without understanding their processes that you attempt to elucidate, while remaining noticeably hostile toward Mormonism before you begin. When, in fact, Catholic theology is more resistant to change than that of Mormonism (assuming that such easy change is legitimately desirable, a characteristic that frankly only liberals believe in). Your criticisms of Mormonism apply to Catholicism but to a much more rigid degree. You need to study Catholicism in more depth to be able to stay credible while writing an article such as this.

“What, for example, would a Mormon theology of sexuality look like”?

What would a Roman Catholic theology of Sexuality look like? It would only be discernible in the context of natural theology, philosophical grafts that were applied well into the middle ages.

What would an Orthodox Catholic theology of Sexuality look like? Ah…now we run into problems that mirror your lamentations of Mormonism.

What would a Jewish theology of Sexuality look like? What theology? Do you mean Law?

What would a Protestant theology of Sexuality look like? Protestant theology? That’s a good one.

Your criticisms of Mormonism highlight a theological ambiguity that is much more the rule than the exception. Where such a theology exists, it is a philosophical graft that can serve a purpose but ultimately isn’t so much religion as it is an attempt to justify man-dictated Law.