There is a crack in everything. That’s how the light gets in. [Leonard Cohen, Anthem]

Although the stories of women in scripture are relatively few, they are “rays of light, hints, promises, glimpses of a greater reality.” [Julie Smith]

Often I think of words as solid, the same way I think of mountains as solid, forgetting that their solidity is an illusion, forgetting they only exist because of the sometimes-violent shifts in the ever-moving plates of meaning beneath. Now I find myself in the midst of one of those rare moments where the old stories are shifting beneath me, lifting and cracking to reveal hundreds of examples of religious women through time in radically direct relationship with God. In reading about women’s spiritual and ecclesiastical authority in early Christianity, early Quakerism, and early Mormonism, I see a repeating pattern in which moments of profound prophetic disruptioni fissure the socio-religious bedrock, allowing the light of women’s spiritual and ecclesiastical authority to stream through, only to see the light dim or the fissure ignored and/or forced closed within a relatively short time.

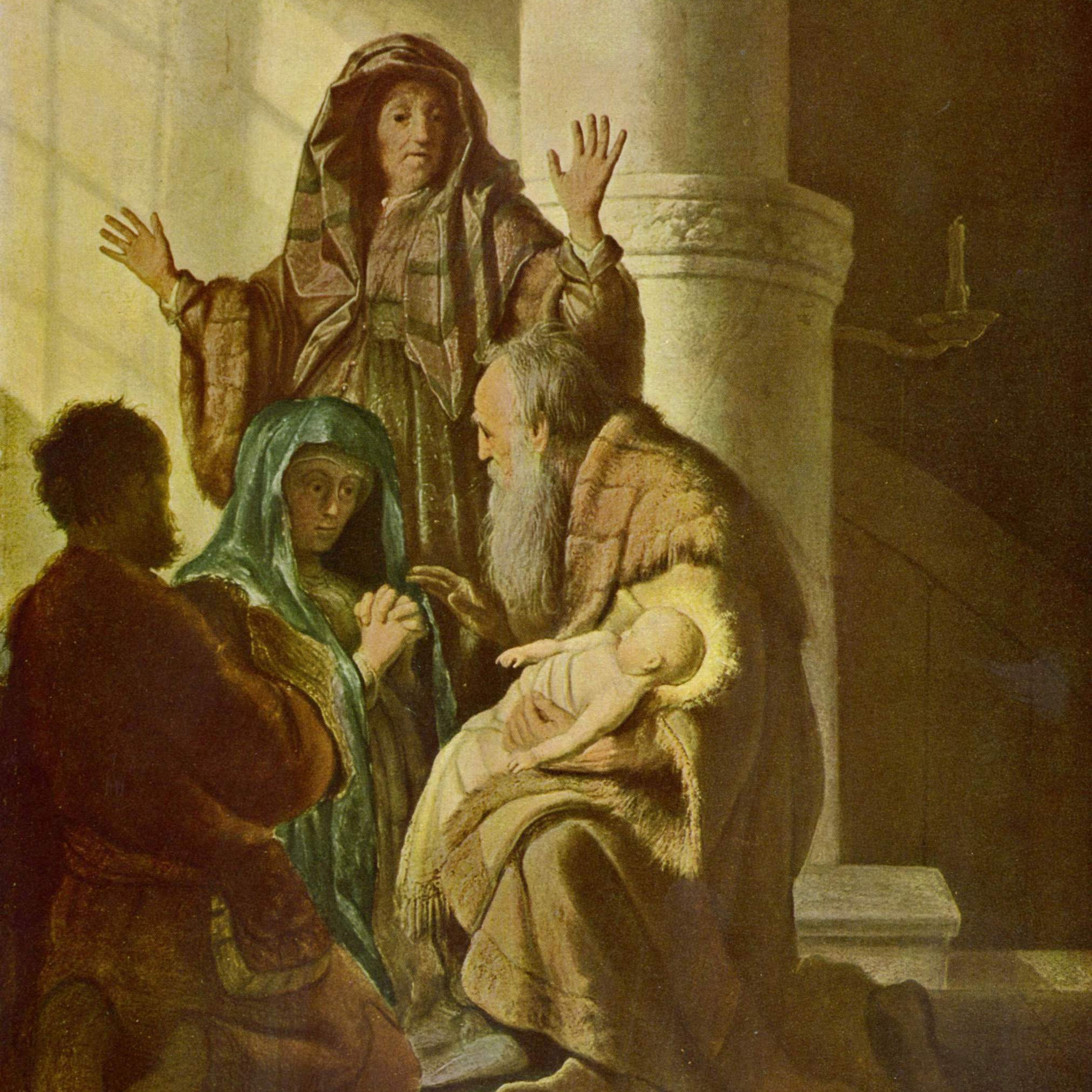

In the early Christian gospels a woman, who immediately recognizes the divinity of the eight-day-old Jesus, wastes no time in prophesying his saving power to her people. She is called Anna and “prophet.”ii A woman with an issue of blood breaks with every social and religious restriction of her time when she reaches for and touches the hem of Jesus’ garment and is healed through her faith.iii The Samaritan woman stands at the well, a person who, by custom, Jesus shouldn’t have even acknowledged. Another woman, this time in direct conversation with God, and the first person to whom Jesus reveals himself as the Messiah. She promptly proclaims her witness of possibility to her people: “Come and see a man who told me everything I have ever done! He cannot be the Messiah, can he?”iv And, of course, Mary Magdalene, who was the first witness of the resurrection and proclaimed that witness to the unbelieving apostles. Marilynne Robinson opens this text further:

When in the Gospel of John, Jesus says to Mary Magdalene, “Woman, why weepest thou?” He is using, so scholarship tells me, a term of great respect and deference. Elsewhere he addresses his mother as “woman”. I know of no other historical moment in which this word is an honorific…In the narrative, [this] is the first [word] he speaks in the new world of his restored life…v

These multiple, beautiful disruptions of “woman” and all that word has meant and means in spiritual and social terms, repeat and repeat and repeat, like a chorus, throughout the gospels. As Jesus causes solid ground to shake and fissure the women emerge from the cracks to prophesy, preach and bear witness of their direct interaction with God.

Women continued to claim and exercise similar authority in the very early Pauline churches. In Romans, Paul writes about Phoebe, “a deacon of the church” and benefactor. He gives Prisca and Aquila, who “risk[ed] their necks” for him, stewardship over the Gentile churches. He also names Junia, who was in prison with him and was a “prominent apostle…before [Paul].”vi

In Corinthians 11: 2-16 the text falters and the light flickers as Paul struggles to incorporate old interpretations of old stories, and current cultural practices, in his description of the proper relationship between God, Christ, Men and Women, in that order.vii These fraught passages are addled with social rules regarding hair length and the horror of a woman speaking in church with an uncovered head. They can be read to reinforce the old tradition of secondary access to God for women, i.e., woman came from and for man, man is her head. They can also be read as proof of women “prophesying” in those early charismatic churches.viii

However, by the time we get to 1 Timothy, Chapter 2:10:12, believed to be written sometime between the end of the first century and middle the second, well after Paul’s ministry,ix the crack in the text closes, covering the sliver of light with the familiar and detailed description of an all-male hierarchy, complete with various titles and offices. Women are instructed in dress and behavior, told to “learn…full submission…[that they may not teach or]…have authority over a man; she is to keep silent.” The creation story is used as proof of woman’s spiritual inferiority, man came first and woman is from man, and the “deceived…transgressor”.x

About 1400 years later, in the mid-1600’s, another itinerant preacher, an Englishman named George Fox, claimed that Christ was alive in each individual who chose to wake to and follow the light of Christ within. He founded Quakerism on a “priesthood of all believers…to model collective apostolic succession, requiring neither priests nor the primary authority of text,” a radical shift in the seemingly solid ground of the hierarchal, scripturally-based authority of the Anglican church. Fox invited everyone, including women “…not only to worship, but also to quake, prophesy, travel, preach and write…”xi

Quaker women “saw the dissenting church and political movements against the Anglican church and social establishments as signs…[that] God was…bringing in a new generation of prophets [female and male] as harbingers of the coming kingdom of God that would overturn the social order.” They believed a true community of Christ meant class and women’s spiritual equality in the church.xii

Based on their direct, often ecstatic, experience of awakening to Christ within, women once again claimed spiritual and ecclesiastic authority. Over the course of the next 50 years these women “prophets” wrote, published and distributed hundreds of “tracts, pamphlets and treatises, letters, and epistles,”xiii in which they interpreted and expounded scripture, criticized and called to repentance King Charlesxiv and the Anglican churchxv and desired “to persuade all those who read their tracts to “overturn” their lives and to live instead in the power of the living God.”xvi They traveled as ministers and participated in “internal church leadership through the women’s meetings.”xvii Many Quaker women were imprisoned, publically humiliated and even tortured for the public expression of their beliefs, which were in near constant conflict with socio/religious laws of the time and in rebellion to predominant social mores.

There are so many pieces written by early Quaker women, it’s impossible to provide breadth or depth in the space I have here. So, I’ve chosen what I hope is a partially representative example from Margaret Fell (Fox). In her tract “Women’s Speaking Justified”, she interprets and expounds on scripture to make an argument for women speaking in church. I was surprised and delighted to find that she used many of the stories I referenced from the New Testament, and many more throughout the Bible to support her argument! Even more remarkable is her disruptive reading of familiar biblical narratives. For example, she has this to say about Adam and Eve: “And first, when God created Man in his own Image, in the Image of God created he them, Male and Female;… Gen. 1. Here God joyns them together in his own Image, and makes no such Distinctions and Differences as Men do.” Fell then proceeds to claim that because Eve was honest about being “beguiled”, God pronounces a “sentence” on the serpent. “I will put Enmity between thee and the Woman, and between thy Seed and her Seed; it shall bruise thy Head, and thou shalt bruise his Heel, Gen. 3.…Let this Word of the Lord, which was from the beginning, stop the Mouths of all that oppose Women’s Speaking in the Power of the Lord; for he hath put Enmity between the Woman and the Serpent; and if the Seed of the Woman speak not, the Seed of the Serpent speaks; for God hath put Enmity between the two Seeds; and it is manifest, that those that speak against the Woman and her Seed’s Speaking, speak out of the Envy of the old Serpent’s Seed.xviii Fell not only claims and supports her right to spiritual/ecclesiastical authority in her reinterpretation of Genesis, but also places those who oppose women’s authority in league with the serpent.

Several things contributed to the dimming of women’s ecclesiastical voice in the Quaker tradition. “One essential aspect of their teaching was that the rigid gender roles assigned by society were evidence of a fallen state of humanity. How exactly to move into redemption from that fallen state became a point of conflict among friends.”xix We see this difficulty played out in an ongoing conflict over separate women’s meetings, which began in the 1650’s.xx As Fox and Fell argued for parallel “meetings of business” for both men and women and as the women’s meetings became more powerful “increasingly handling discernment over marriage”, splits arose. “Whilst the spiritual equality of woman had been a keystone of early Quaker thinking, it did not extend to political equality” in every Quaker’s mind. An additional reason may be that as the “eschatological emphasis” waned and the “transformation of the world seemed less imminent, more traditional [gender roles] resurfaced.”xxi Over time there were also schisms within the larger tradition, some toward more conservative Protestant practices, including the adoption of ministers and a return to elevating scriptural authority over the inner light. Others, such as the Hicksites, rejected scripture as authoritative and relied only on the inner light.xxii It was within the more radical meetings women tended to keep more authority and in the more conservative, a kind of male hierarchy reappeared. However, it is important to note that throughout their history Quaker women have enjoyed much more equality in church governance and spiritual authority than in almost any of the other Christian faiths.

Early Mormonism is similar to early Quakerism in many ways. The main difference is limited access to priesthood authority, which almost immediately complicates early Mormon women’s direct access to God and thereby their spiritual and ecclesiastic authority within our tradition. Unlike Paul or George Fox, Joseph Smith claimed God’s priesthood authority was restored through him and passed on through him, as the only and chosen prophet. However, while the fissure is thinner and women’s authority more fraught, it still manifests. Within a matter of months of the priesthood being restored to Joseph, he also receives D&C 25:7-8, in which God tells Emma “thou shalt be ordained…to expound scripture, and to exhort the church according as it shall be given thee by my Spirit. For he shall lay his hands upon thee, and thou shalt receive the Holy Ghost, and thy time shall be given to writing, and to learning much.”

In her essay “Mormon Women and Priesthood” Linda K. Newell also points to D&C 46 as formalizing the ungendered practice of spiritual gifts that were already “manifest in the church,” which included women blessing, prophesying, and speaking in tongues. It took twelve years before the formalizing of a female equivalent to the male priesthood began. With the organization of the Relief Society in 1842, Joseph proclaimed that he would “ordain them [women leaders] to preside over the society…just as the Presidency preside over the church.” And at the third meeting, thirteen days later, “that the Society should move according to the ancient Priesthood…he was going to make of the Society a kingdom of Priests as in Enoch’s day—as in Paul’s day.” Around this same time Newell K. Whitney proclaimed, “without the female all things cannot be restor’d to the earth—it takes all to restore the priesthood.”xxiii

Unfortunately that vision for a “parallel” priesthood for Mormon women was never fully realized and a distinction between the practice of spiritual gifts and priesthood began soon after Joseph’s death. Mary Ellen Able Kimball, trying to understand that distinction, recorded this explanation from Heber C. Kimball in her journal “inasmuch as they are obedient to their husbands they have a right to administer in that way [anointing the sick] in the name of the Lord Jesus Christ but not by authority of the priesthood invested in them for that authority is not given to woman.” However, Emmaline B. Wells was called “prophetic” and Orson Pratt said, “there never was a genuine Christian Church unless it had Prophets and Prophetesses.”xxiv This back and forth is representative of the confused language in and around Mormon women’s spiritual/ ecclesiastical authority into the early twentieth century.

However, we also know that Relief Society early on was an autonomous organization and that Mormon women wrote and published, albeit for a female audience, extensively once they’d settled in Utah. Vella Neil Evans argues that because these publications were not only “sanctioned” by the church, but women were “called” to write, it gave their discourse authority. Although much of the writing was orthodox in nature, supporting the patriarchal hierarchy and the practice of polygamy, early Mormon women claimed their spiritual/ecclesiastical authority where they could.xxv For example Eliza R. Snow assured women they would be receive “instruction” from the Spirit of God, which they should “impart to each other.” She also answered the question of whether women should be set apart to perform washings and anointings, or for the laying on of hands in ministering to the sick by saying it was not necessary. She proclaimed that any worthy, endowed woman “not only has the right, but should feel it a duty…to administer to our sisters in these ordinances, which God has graciously committed to his daughters as well as to His sons” and promises them the “Almighty power of God” in such ministry.xxvi

Almost from the beginning of Mormonism there was a lack of clarity about the nature of women’s spiritual and ecclesiastical authority. Gradually, after Joseph’s death, and in the years that followed, the male leadership’s language moved away from a parallel priesthood, becoming increasingly hostile even to women practicing spiritual gifts. Eventually in the mid-twentieth century, the practice of women administering blessings, this last vestige of women’s early authority, was stripped away by Joseph F. Smith, then prophet. Ecclesiastic and spiritual authority belonged soley to the hierarchy of an all-male priesthood.

Although these prophetic disruptions occur in distinct periods and faith traditions, the expansion and recognition of women’s spiritual and ecclesiastical authority in each tradition is strikingly similar. In each of these periods women broke with existing spiritual and cultural restrictions in significant ways and claimed the authority to actively witness, minister, and lead in their communities. And in the Quaker and Mormon traditions, though the level of authority differed, to write extensively. These series of cracks where spiritual reality splits open the man-made religious constructs of the feminine relationship with God suggest to me a fundamental truth, namely that women’s spiritual and ecclesiastical gifts are as broad and their voices as significant and essential as men’s to even approaching a full understanding of God. But whether through conflicting ideas followed by neglect, as in the case of the Quakers, or what appears to be a combination of an inability to reconcile old ideas with new truth and/or willful boundary drawing around ecclesiastic authority in the early Christian and Mormon traditions, the momentary cracks of light close in favor of the old stories, told in the old ways, all the while ignoring the texts that challenge and shift traditional ideas about both men’s and women’s true relationship to God.

- Krista Tippet, On Being: The Prophetic Imagination, Walter Brueggemann http://www.onbeing.org/program/prophetic-imagination-walter-brueggemann/475

- New Revised Standard Version (“NSRV”), Luke 2:36, 38.

- NRSV, Mark 5:25-34.

- NRSV, John 4:27.

- The Death of Adam: Essays on Modern Thought, Marylinne Robinson, Picador: New York, 1998. 241.

- NRSV, Romans 16:1-7.

- The texts I’m citing are not chronologically ordered, but ordered in a way to show how the complication of women’s spiritual/ecclesiastical authority might have begun.

- Non-hierarchical groups, where individuals came together to exercise their spiritual gifts in community. The Great Courses, History of the New Testament, Bart Erhman, Lecture Four: The Problem of Pseudonymity

- G.C., History of N.T., Bart Erhman, Lec. Four: Prob. Pseudo.

- NSRV.

- An Introduction to Quakerism, Pink Dandelion, Cambridge University Press: New York, 2007. 22-24, 36.

- Ruether, Rosemary Radford. Forward. Hidden in Plain Sight: Quaker Women’s Writings 1650-1700, Mary Garam, et al., Pendle Hill Publications, Pennsylvania, 1996. xiii-xiv.

- Ibid., Mary Garman. Introduction. 9.

- Ibid., Margaret Fell, A Letter to the King From M.F.: King Charles I defie thee to Read this over, which may be for they Satisfaction and Profit, 1666. 42-46.

- Ibid., Esther Biddle, The Trumpet of the Lord Unto Thefe Three Nations, 1662. 129-36.

- Ibid., Saraah Blackborow, A Visit to the Spirit in Prison, 1658, 47-57.

- Ibid., Ruether xiv.

- Margaret Fell, Women’s Speaking (http://www.qhpress.org/texts/fell.html).

- Garman. Intro. 8.

- A Quaker Meeting refers to a group of people who come together in community and worship. Other sorts of meetings are called to manage the concerns of the group. These are also referred to by the term meeting, e.g., the meeting of business.

- Intro. to Quakerism, Dandelion. 47.

- Elias Hicks: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Elias_Hicks

- Linda King Newell. “Mormon Women and Priesthood.” Women and Authority. Ed. Maxine Hanks. Salt Lake: Signature Books, 1992. 24-25.

- Ibid., Newell. 25-29.

- Ibid., Evans. “Mormon Women’s Publications.” 49-51.

- Ibid., “Historic Mormon Feminist Discourse—Excerpts.” 72, 85.

This is so wonderful Twila!

thank you for your thoughts.

My pleasure, Lauren. Thanks for reading.

I love the image you use of fissures and cracks of light. While it breaks my heart that these small fissures keep being closed by our smallness of mind and reliance on old stories I know that it cannot last forever. One day the fissures will open so wide that they cannot be covered. And then we will all bathe in the light and love of God. Thank you for this, Twila!

Really great writing. Great job!

This is among the best posts I’ve read on the bloggernacle about women and the church – and not just because you and I are family, but because it is courageous and thoughtful and full of truth about a (the) foundational problem (patriarchy) in the church. Thank you for the time and energy you took to write this, Twila. And for being willing to share it here. I’ll read it again and again.

Michelle Snow,

Thanks, Michelle!

Melody,

Thanks, Melody, for your comment, and all the conversation over the years that has energized, informed and enlightened my own seeking. Love you.

mraynes,

mraynes,

Yes indeed, Meghan, it’s time for the big one to hit!

Michelle Snow,

Thanks, Michelle!

Wonderful work, Twila!

Very nicely done. Thank you.