By Sheldon Greaves, Ph.D.

Genesis 38 tells a strange story, set in a foreign culture that carries resonance because in the end, it is both a story of survival and of justice.

Briefly stated, it is the story of Tamar, the daughter in law of Judah. She was married to Er, the firstborn son of Judah, but before they had any children Er died suddenly. The death is ascribed to God because of Er’s wickedness, but there are no specifics. There is no announcement or oracle from God explaining what happened, it is simply assumed by the author. It was common in the ancient world to attribute such a terrible thing as untimely death to some external reason, something to help make sense of things that defy the way the world should be.

Nowadays, we use conspiracy theories. But I digress.

We now get a introduction to the law of the levirate, which was the duty of some other close family member to beget a child by Tamar, to give her a family. As we’ve mentioned before, and as I explain at length in my Old Testament podcast “Abraham in the Desert” to be a single, childless woman in those days was very nearly a death sentence. Without progeny to take care of them as they grew older, women in such straits could look forward to privation and premature death. This is why the levirate was so important. Tamar had a right to progeny and descendants. The key to that right was her father-in-law, Judah.

So Judah sends his son Onan to give a child to Tamar, but he famously does not fulfill his obligation. He “spills his seed on the ground,” which suggests some form of coitus interruptus but end results are unmistakable: Tamar isn’t pregnant, and Onan pays for his failure with his life.

The text indicates that Onan did not carry out his duty to raise progeny for his brother Er out of self-interest. He did not want to enhance the family of his dead brother. Political power went to the most numerous. Another thing we know from the Bible is that the levirate was not terribly popular; it certainly wouldn’t exactly generate domestic harmony with their own spouses. In fact, Deut. 25:7 concerns legal contingencies for a widow should her brother-in-law refuse to give her progeny.

Another thing worth noting is that in later texts such as Deuteronomy the levirate is a marriage. But in Genesis 38 Tamar is not claiming the right to a husband, only the right to descendants.

The story of Tamar, Judah, and Onan is a very secular story; apart from the mention of God as the cause of the deaths of Onan and Er, we have no angels, no visions, dreams, burning bushes or pillars of smoke. There is no sacrifice, no religious rituals at all; Tamar does not even petition God or ask for his favor. She takes matters directly into her own hands, ready to risk everything in order to claim what is rightfully hers.

Cylinder seal and impression on clay: banquet scenes. Shell-(?), Early Dynastic III (ca. 2500–2400 BCE), found in Mari. Wikimedia image.

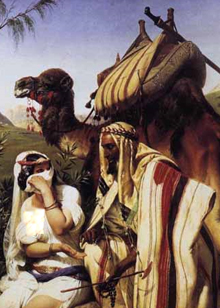

But back to our story. Judah has one son left, his youngest son Shelah. He demurs from sending him to join with Tamar, claiming that he is too young. Tamar lives with her father’s family, but Shelah grows up and has not been given to her. It is at this point, just after the death of Judah’s wife, that Tamar plays her famous ruse, posing as a prostitute and seducing Judah. Tamar needs two things from the encounter: Judah’s child in her womb and physical proof of the parentage. Judah’s staff and seal on its cord suffice. The seal would have most likely been a cylinder seal by which Judah could affix his “signature” to a commercial document. The staff was a symbol of authority and would have been easily recognizable to all.

Afterwards, Judah sends the agreed-upon fee of a kid, but the prostitute is not to be found. In verse 20 the word for “prostitute” is often translated as “temple prostitute” or “hierodule” because it is based on a verb meaning “to be sacred.” However, much scholarship over the last few decades have failed to demonstrate any clear evidence of this kind of “sacred prostitution” in ancient Israel, Canaan, or Babylon (See my podcast on “Kickin’ It With the Canaanites”). It seems more likely to me that this term was a wry euphemism, much the same way we might call a woman who manages a modern-day brothel a “madam.”

Meanwhile, Judah decides to let the matter of his seal and staff drop, but few months later notices that Tamar is pregnant. The only conclusion is adultery; a very serious offense. The sign of pregnancy is enough for conviction; there is no inquiry, let alone any kind of trial. The sentence of burning was a very old one, and the prerogative of the family leader at this point in Hebrew history.

There is a subtle point here; Tamar is about to be punished for adultery, not prostitution. The Old Testament does not contain any legislation that specifically forbids prostitution. Judah comes under no censure implicitly or explicitly for employing the services of a prostitute. His biggest concern was that he paid for it.

When Tamar demonstrates that Judah is the father of her child (twins, as it turns out), he acknowledges that he was in the wrong. At the end of the day, the text portrays Judah as an honorable man who corrects his mistake, even though it would have been a heavy blow against his authority.

Tamar is one of those stories among the patriarchal narratives where a disadvantaged woman takes the initiative to get what she needs, even if it means dispensing with custom or cultural mores. Biblical scholar Claus Westermann notes that, “It is characteristic of the patriarchal stories that revolt against the established social order, where it is a question of injustice, is initiated by women only. And in each case the justice of such self-defense is recognized.”[1]

Dr. Sheldon Greaves holds a Ph.D. in ancient Near Eastern Studies from the University of California at Berkeley. He is also a Scholar-in-Residence at Christ Church Episcopal in Portola Valley, CA, and adjunct faculty member at Stanford University.

Dr. Sheldon Greaves holds a Ph.D. in ancient Near Eastern Studies from the University of California at Berkeley. He is also a Scholar-in-Residence at Christ Church Episcopal in Portola Valley, CA, and adjunct faculty member at Stanford University.

Dr. Greaves also hosts a weekly podcast, Discovering the Old Testament, available here: http://www.lafkospress.com/discovering-the-old-testament-2/

[1] Genesis 37-50. A Commentary. John J. Scullion S.J. (Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House) 1982, p. 56

Dr. Greaves, I really appreciate your insight. I’m smarter now than I was before. Thank you.

I love reading articles such as this. Thank you.