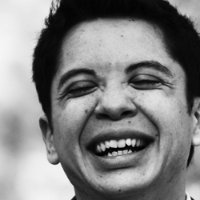

I recently had the honor to interview a very talented, thoughtful, and all around awesome LDS musician. I first got to know David Lindes through my brother’s LDS music blog, Linescratchers. I was impressed by his musical/songwriting talent, but I was also impressed that he didn’t shy away from relevant, urgent social messages. I work a lot with immigrant families, and I feel like David’s music gives a voice to immigrant families in the United States and reveals many insights into their struggles and dreams.

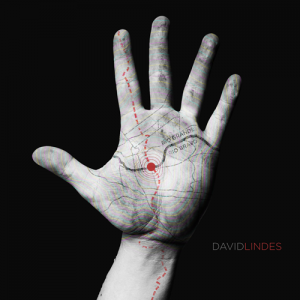

David recently completed his first solo album, David Lindes. He was recently featured on NPR’s Weekend Edition, as well as NPR Alt.Latino. His song, ‘Caminante Caminando’, was a finalist for a John Lennon songwriting award. David is definitely a rising star in the growing Latin Alternative community, and his music is receiving wide praise and acclaim.

First of all, tell us a little bit about yourself. Where are you from? What got you into music?

I’m from Guatemala City; from a humongous low-income housing project called Colonia Primero de Julio. It was built in the ’70s. I wouldn’t call it upscale. It was a great place for a kid with a bike, though. A multilevel maze of concrete stairs, ramps, runways, and innocent pedestrians. Every little boy’s dream.

I got into music the same way everyone does, I guess: by listening. Growing up, the neighbors across the way played really loud rancheras (Mexican regional classics), so those were inevitable at our place. My mom loved the Beatles, Cat Stevens, and Simon & Garfunkel. My older uncle listened to Latin American protest music (Silvio Rodriguez, Pablo Milanés, Violeta Parra), and his younger brother dug the pop (Queen, Michael Jackson). Of course, there was lots of less-inspiring music to go around as well. In fact, just the other day I was going through one of those online lists of the worst songs ever written and I came across Patrick Swayze’s single hit: “She’s Like the Wind”. Dude, you’re gonna laugh, but nothing takes me back to early nineties Guatemala City like “She’s Like the Wind.” I mean, the transportation it’s physical, it’s real. Yup. Also, Central American cumbia was all over the single adult dances my divorced mom attended. Of course, my sister and I came along to run around the dance floor and eventually fall asleep on those hard wooden benches, and I still can’t un-hear a lot of those songs. Look up “Sopa de caracol” for me. Listen to it. Yeah. You’re welcome. (Link for the lazy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=N5732nPEJNs)

I do remember thinking Michael Jackson was the epitome of musical excellence. Of course, between the ages of 6 and 9 I could hit all of his notes with surprising vigor. Sitting on a frayed armchair in my grandmother’s house in Guatemala City, singing Billie Jean; that’s when I first knew I was a musician.

Your latest album, David Lindes, is fantastic. Why did you write this album? What happened to the initial title, Adios Macondo?

Your latest album, David Lindes, is fantastic. Why did you write this album? What happened to the initial title, Adios Macondo?

Adiós Macondo was an artist name I was planning on using back when this whole thing was just an idea. After a while, though, I realized this record would be bilingual, and Adiós Macondo is quite the tongue twister for the English speaker. I opted to simplify and just use my name.

I think two things fueled the songwriting this time around: an awakening and a homecoming.

I came to the U.S. when I was 9, and the truth is, I had no idea what I was doing. I remember the day we left: relatives crying in a vast hall in the airport. When I saw my uncle cry, I knew something was wrong. I knew there was something going on that day that was over my head. But, of course, I had no idea what it was. It didn’t occur to me that we wouldn’t return to Guatemala for years. I didn’t know I’d miss family. I was blinded by hope, really. That hope was vast and childish. I knew Ninja Turtles action figures would only be $5 a pop in the U.S. I basically thought I’d live on the set of The Wonder Years. I’d been told you could find Nintendos and fully-functional televisions in people’s garbage cans. That’s where my gaze was, and for the life of me I couldn’t see what I was losing. Well, I think in the last few years I’ve become aware of that loss. Immigration is tough on the human heart, man. It severs your sense of identity irreversibly. It’s not just the macro things that it breaks: family, food, culture, tradition; it’s also the micro stuff; your routine, the way you used to bathe yourself with a bowl and a drum of water, the fact that if you get on a bus with the right number on it, it’ll take you to your favorite pizza place, the way grandma’s hands smell like watercress and cigarettes. You lose all that and you begin again. It’s a strange kind of re-programming. And don’t get me wrong, I think in the end you come out winning. I feel like I have. I get to be the master of two cultures. But I also understand the pain I’ve gone through now. I hate to be my own shrink, here, but sometimes it feels like someone cut me and it took me twenty years to scream.

So that increased awareness of pain is part of the awakening. Another awakening was a political one. Somehow, the immigration issue has convinced me that my life and the lives of people I care about are inseparably bound to policy. We all have that moment when we realize we’re not an island, and the decisions made by people we don’t even know could affect us intimately, definitively. Watching undocumented immigrants be portrayed as lazy and dangerous did that for me.

The homecoming is the other side of the coin. The only reason I realized I had been hurting for twenty years was because it stopped. The contrast is what got my attention.

It’s really been about my wife, Noel, and our three small children. We’ve begun to build something, man. The gravitational pull of our little family is now much, much stronger than that of my childhood in Guatemala. I’ve switched orbits, and that feels great. Again, it happens in big and in small ways. About a year and a half ago, we bought our first home. Suddenly, I felt like maybe if someone asked me where I was from, I could honestly say “Salt Lake City” and not have it be a lie. I haven’t done it yet, though. 🙂 I’ve watched our children be born. When our oldest arrived, it was like someone turned on the light. It was gentle, quiet, but life-changing. He started pre-school two weeks ago and we ride our bikes together to school every morning. And when we do, man, I don’t miss Guatemala. I don’t miss anyone or anyplace. And to me, that’s what defines home; an absence of longing. Of course, for me, it comes and goes. And I’m fine with that. What’s special to me is that it’s come at all.

Those two things made me want to tell my story. And when I did, I found that my story was bound to the stories of other immigrants I had grown up around. My love and respect for them and their experiences came forward, and that’s how this album came together.

Who would you say are your major influences? Not just musically, but artistically?

I’ve had a few moments here and there where whatever I’m listening to or looking at, or reading, just stops me; just grabs me by the throat.

I remember being about fifteen. My mom and I were running some errands somewhere between Watsonville and Santa Cruz on California’s central coast. A song came on that I’d heard hundreds of times as a child, and I immediately settled into it; like sitting on an old couch. It was “Let It Be”, by the Beatles, and that was when I realized I had been a Beatles fan all that time. Years later I bought my mom every Beatles record ever made. It’s something we still share.

When I was a senior in High School, I took an AP Spanish Literature class. It was taught by a jewish woman from New York, named Ms. Fairhall. Can you imagine that accent when she spoke Spanish? It was golden, man. She was amazing. She absolutely loved the books we read, and she was adamant that I should, too. And she was right. I had spent the last few years of my life running away from Latin America. I was living in Watsonville at the time, and I saw a lot of lousy intercultural communication. White folks had some negative stereotypes of hispanics. They included the uneducated, dirty fieldworker; the knife-wielding, wifebeater-wearing, slick-haired, pot-smoking cholo, and others. I basically ran away from being hispanic because I didn’t want to be associated with those stereotypes. That is, until I read Borges, Asturias, Unamuno, and Márquez. Suddenly, I wanted these authors to be mine. I wanted to associate with them. And that meant being hispanic. Over the years, I’ve grown to love the story of the migrant farmworker, and I think that’s evident in a few of the songs on this record. “Mi Tierra” and “Caminante Caminando” come to mind. I’m still not a fan of cholo culture, but I do love me a nice lowrider. 🙂

I served a mission for the LDS Church in El Salvador. My first area was a small town called Chalchuapa. One morning, we came out the front door to find a marching band banging down the street. But it was unlike any marching band I’d ever heard. Their sound was deeply syncopated, and though they weren’t terribly tight, the sound hit me hard. I think that’s when I decided that Latin America had something magical about its music, and that I wanted that to be mine as well. The time leading up to my mission was spent listening to ’60s and ’70s folk and rock, so I hadn’t explored Latin American’s sonic landscape. That little marching band was my baptism, really. To this day I don’t have a name for what they were doing. Maybe they were kind of a bad samba school?

After my time as a missionary, I spent a few weeks with my dad and uncle in Guatemala. I hadn’t been back for so long. It felt amazing to be back. We rented a car and drove from Guatemala City to Tikal, and to keep us entertained we had only each other and a couple of Silvio Rodriguez records. I still remember the first time I heard “Imagínate”. It was showing up late to the most important party of your life. Suddenly I knew that this world of Latin Folk and protest music existed. It had existed for decades. Someone had been writing the kinds of songs I wanted to write for THAT LONG. It was urgent for me to get started.

Your musical style is hard to pin down. You bring a lot of diverse influences together, creating an amazing blend that sort of encapsulates the diverse Latino experience in the United States. Why did you decide to cover so much ground musically? Was it a conscious artistic choice to use different styles, or did the blend occur more naturally?

Listening to music in both languages was inevitable for me. At first, it was Maná and Counting Crows. A few years later it was Silvio Rodriguez and Cat Stevens. For a long time I saw those two sonic worlds as separate, and I saw my music populating the Spanish-speaking of the two. In fact, that’s partly why I’d use the pseudonym Adiós Macondo. I was focused on Latin America for a long time.

About halfway through the songwriting process for this record, both my wife Noel and Edson, who produced the record, began asking me why I didn’t write any songs in Spanish. I think for a long time my music was one of the only ways I had to explore my Latin American identity. So I sang in Spanish, I sought out pan-Latin influences, and I tried to become part of that musical tradition. I was trying to be a real Guatemalan, I guess.

During that time, writing in English felt awkward, because sonically I was always writing Latin-influenced stuff, and so, for instance, I’d deliver some pretty stilted English lyrics over a Bolero or something. Then, recently, it occurred to me that I could write songs in English that leaned more heavily on my English-speaking influences. I ran with it and began to write stuff that pulled on Americana, Pre-war Blues and Gospel, Irish drinking songs… 🙂 It was liberating and tons of fun.

So I wrote “Cross the Water” as a blues tune. When I wrote that song and performed it, I was doing my best to be Bukka White, basically. But blending those old American roots influences with the Latin Folk stuff I’d grown to love was inevitable. I think I’ve begun letting those two musical spaces connect. I poked a hole in the wall between them, and started having fun with that. I think it’s a decent start. You can hear it throughout the record, and it’s something that kinda sprung naturally from my background. If anything, I just had to open up and let it happen, instead of insisting on segregating my musical influences.

How have your religious beliefs informed your art?

First, my faith taught me a love of insight. In the Mormon church we do this thing where we assign people to talk, right? And real insight – a thought that is pure and clear, thought-provoking and free of clichés – is prized and rewarded. We come home and say “wow, that was a great talk!” I grew up with that feeling of listening to something that fiddles with your insides, you know; something that has real spiritual power; something that makes you think deeply about yourself, about your life. I love that feeling, and I try to look for it when I make music, and I do find it from time to time. Honestly, that feeling is the reason I make music. And to me, when I find it, it’s a miracle. It’s my pillar of fire.

Another thing I learned at Church: the power of sacred music. There is this idea that when you’re singing about things that matter, weighty things, important things, urgent things, you have real power. Power that flows from God. Now, in Church, we sing about Jesus or his teachings, right? Well, I don’t do that directly in my music. I don’t proselyte, but I do write about what matters to me, because music is a tremendously incisive tool for delivering urgent messages. It cuts right through your meat and your bones and it speaks to your spirit in its native language. That power is something I first encountered in primary. When I was 7 in Guatemala City I was asked to sing a solo in sacrament. It was “I Believe in Christ”, and I remember being terrified, but I remember watching members of the congregation cry as I sang. Dude, it was traumatizing, but it was special. That was my introduction to the spiritual power of music that means something, music that comes from the depths of your guts.

On a final note, the songs are filled with biblical references. For example, in “Mi Tierra”, in the second verse, there’s this line- “Lava tú los platos, limpia tú los baños/Suda tú en los campos, gasta allí tus años/Deja a tu familia pa’ labrar la tierra/Luego ven y tira la primera piedra”, (You wash the dishes, You clean the bathrooms/You sweat in the fields, and waste away your years there/You leave your family to come clear weeds/And then cast the first stone) which is a reference to Christ’s matchless words when encountered an angry mob and an adulterous woman; a simple, loving, effective appeal to empathy. In “Caminante Caminando”, in the first verse, I talk about “poder partir en dos las aguas del Río Bravo” (to be able to divide the waters of the Rio Bravo/Grande, depending on which side you are on), which is a reference to Moses’ knack for getting water out of the way. “Devil’s Gonna Fall” is basically about the great and terrible day of the Lord, man, when the humble will be exalted and the proud will be brought low. Also, “Cross the Water” is a prayer for God’s help in cross the border alive. So my faith is really all over this record, and has influenced a lot of my thoughts when it comes to the themes of the songs. Immigration is all over Mormonism’s DNA, man, and I love that. Lehi takes off for the New World, Nephi flees the murderous company of his brothers to preserve his safety and that of his people, Joseph Smith flees city after city until he is killed, and then Brother Brigham finishes the job. We know what it’s like to flee in search of peace, or at least survival. We know that the search for peace is a sacred search, and that’s what I tried to capture with this record. “Cross the Water” plays with some old African American Spiritual sounds to tell the story of crossing the U.S.-Mexico border illegally. In old slave songs, the message was about crossing the River Jordan, into freedom, as a parallel for crossing the veil into death and glory. Like our journey to heaven is sacred, so is our journey to peace and freedom, and those old spirituals capture that like nothing else I’ve ever heard. That’s why I tried to reference that sound, that tradition, that story, in “Cross the Water”.

What can we expect from you in the future?

We’re still pretty early on in this record’s life cycle, with the release now a few months behind us, so I’m looking for ways to make these songs matter, to make them reach and influence the folks who are most likely to be open to them. I’ve also been writing a lot about the experiences that led me to write these tunes on my blog (davidlindes.net/blog) and I’ve had a great time doing it. I’m considering expanding those thoughts and notes into a self-published book that includes the songs themselves, the stories behind them, and some family photos of the experiences I write about and some visual artwork that backs it all up.

Also, I think this record was a breakthrough for me as a writer. I feel like the effort I put in allowed me to find new plots of land to sweat over. But I also feel like most of the land I discovered is still virgin. So there’s a lot of work to do, man. Like I said about my multicultural influences, I barely managed to poke a hole in the wall between them this time around. I need another shot at it, and this time I’ll do some real damage. So there’s definitely more music coming.

Finally, I’ve been working to find opportunities to write for other artists. It’s a different puzzle altogether, and it gives me a chance to write in genres I don’t currently perform. For instance, I love the simple storytelling tradition of Country music, or the “shut up and dance” attitude of a lot of today’s pop. I want a chance to take my craft as a songwriter for a spin in those environments, and I wouldn’t necessarily go there as a performer, but as a writer? Bring it on, man.

Buy David Lindes’ self titled album, David Lindes, here!

I enjoyed both the interview and the video. Thanks.

Awesome. I found his answers to be really poetic and inspiring.