Any conversation that opens up space for honest discussion of women within Mormonism is good, and the church’s newest essay “Joseph Smith’s Teachings about Priesthood, Temple, and Women” brings the topic of women and priesthood authority into that space.

The gospel topics essays have become a new genre of church communication: abbreviated, footnoted, authoritative treatments of problematic topics from church history. All of the gospel topics essays seem to be responding to specific rumblings from Mormon progressives, and whether or not this is precisely the case, the essays often offer some support, many counter-arguments, and a standard non-threatening LDS interpretation of issues that have been hashed out in progressive circles. They are subversion and containment essays. While these essays will never meet my personal needs of engaging problematic topics in full, historically accurate, and nuanced ways, I recognize and appreciate them for what they are: a brief introduction for the general LDS membership to topics that were previously off limits, heretical, or dangerous to discuss.

Certainly “Joseph Smith’s Teaching about Priesthood, Temple, and Women” is riddled with historical gaps and interpretations of facts that align with the status quo, but one has to put it in context with this new genre of essay, it provides a solid starting place to familiarize the wider church population with issues regarding women that have long been known to LDS scholars and more recently known to those who have been seeking to reconcile the church and feminism. That said, the essay is misnamed. Very little space is actually given to Joseph Smith’s teachings themselves and more is given to modern-day interpretations of 19th century ritual practice. The name implies that the essay will end controversy around what Joseph taught about the priesthood, the temple, and women, when in fact the essay is entirely about women; however, I find it telling that the essay deals with the three most prominent historical arguments used by those seeking female priesthood: ordination of women in the early church, women healing and blessing, and co-gendered temple worship. (The fourth argument is of course the existence of Mother in Heaven, which was given an essay of its own released concurrent with this one).

Ordination of Women in The Early Church and Temple Participation

As a student of LDS women’s history, specifically women’s participation in healing and blessing rituals, I have long dealt with the problematic yet fascinating play between the priesthood, the temple, and the Relief Society—and part of what makes these problematic is the significant lack of an understanding of Joseph’s intentions and plans. We do not know what Joseph had in mind for women,[i] but we cannot read what was in place at his death as the fulfillment of his intentions and the definitive statement of his understanding of women’s “rights and privileges.”[ii] This puts us in a bind; because we do not know how the role of women would have evolved if Joseph had not been martyred, there exists space to envision that evolution in the most liberal of terms. At the same time, because we do not know Joseph’s wider vision for women, we do not know how he at that time would have understood and explained the true significance of turning the key to the ordained presidency of the Relief Society, and this constrains us and requires us to be responsible in our envisioning of that very same potential evolution.

Many today make the assertion that because women were ordained in the early church, they must have been given the priesthood. There are many instances of women being “ordained” to minister, heal, preside, and administer in holy ordinances. Many women record being “ordained and set apart” to these responsibilities. While the first of these instances occurred at the founding of the Relief Society in Nauvoo, women were still being “ordained” as late as the 1890s.[iii] However, no public record exists that records a women being ordained to a specific office of the priesthood, and, as the essay explains, our 21st century understanding of the term “ordained” is not immediately transferable to a 19th century understanding. The fact that many women were “ordained” in the first 50 years of the church does not directly lead to the conclusion that early LDS women held priesthood office. While some today might feel strongly that the use of the word “ordain” in regards to early LDS women stands as proof that these women held a priesthood office, there is in fact no historically responsible evidence that these same women understood it to be so.[iv] That said, this new essay asserts that “ordain” was used in a broad sense, that it could be interchangeable with “set apart”; I find this a touch disingenuous. It is clear from journal entries and recorded blessings that “ordain” was distinct from “set apart”; women who were ordained tended to be higher in rank or status, called to a position of authority or special prowess (such as those called to serve in Relief Society presidencies or called to train to be midwives), and—after the establishment of the Relief Society and the subsequent availability of the temple endowment to women—theses women tended to be endowed sisters. Under these circumstances, women who were “ordained” as well as set apart were being blessed with an extra measure of power and authority.[v]

The endowment of women in the temple is central to the discussion of women in authority, yet the essay glosses over an important moment for endowed women leaders in the church: their participation in the Anointed Quorum. I expect this gloss is due to the fact that there is currently no other essay that touches on the existence of the quorum. It was only when Emma Smith was endowed that this group of priesthood leaders became a complete quorum, and as the wives of these leaders were endowed themselves, the quorum became balanced between the genders. Together these men and women would receive revelation and direction for the church; they would participate in collaborative healing and prophesying. Certainly this is that to which the essay alludes when it explains that Joseph introduced temple ordinances to a “core group of men and women.” The essay goes on to say that temple ordinances in and of themselves do not “bestow ecclesiastical office on men or women.” While this is true, the ordained woman (and in Nauvoo this woman would have been married and sealed to her husband), was understood to have a power and authority greater than that of a women who had not been through the temple.[vi]

Women Healing and Blessing

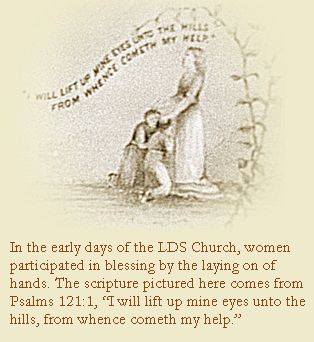

This power and authority was directly connected with women participating in healing and blessing rituals. As the essay discusses priesthood and the temple, it ends with a paragraph that explains “When a man and a woman are sealed in the temple, they enter together, by covenant, into an order of the priesthood.” For over 100 years, LDS women laid their hands on their husbands, their children, their friends, and their neighbors—both men and women. They used consecrated oil, they invoked temple washing and anointing rituals, and they cultivated the gift of the spirit to heal. They prophesied, developed their faith and authority, and they laid hands to offer blessings: mother’s blessing, sister’s blessing, matriarchal blessings. For at least sixty years, women would seal their blessings, often times doing so by the power of the priesthood they shared with their husbands.[vii] The essay quotes Eliza Snow explaining that women do not administer “by virtue of the Priesthood,” yet it does not place this quote in the context of the fighting between John Taylor and Eliza Snow over women’s authority nor does it acknowledge the instances in which Eliza claimed otherwise. No, women were not ordained to priesthood office, but they certainly understood themselves to have access to a priesthood power and authority by virtue of their temple endowment and marriage sealing.

There are many reasons for the decline (as the essay names it) of women’s participation in blessings and healings, just as there are many reasons for the loss of women’s understanding of their participation in the priesthood. The essay makes it appear that this decline was natural—more of a progression towards the natural order of things (“call for the elders”). Again, I find this simplification problematic. Certainly a gospel topics essay is not the place for a fully developed academic treatment of women healing and blessing; however, the essay presents a clean and easy explanation for women’s retreat rather than an acknowledgement of fifty years of struggle between the male and female leaders of the church as the women tried to keep the rights and privileges they believed Joseph had bestowed upon them.

A Starting Point

It has been less than a day since the church posted “Joseph Smith’s Teachings about Priesthood, Temple, and Women,” and the reactions have ranged from heralding it to condemning it. I find myself somewhere in the middle. At times the essay smacks of an attempt to contain the best historical arguments used by those agitating for female ordination, other times it loses its way from being about Joseph’s teaching and instead rests its assumptions and conclusions firmly in the teachings of more modern prophets. I recognize I am not the ideal audience; the points and illustrations the essay presents are not new to me. Over the last fifteen years the church has released all of this information and more, and those who have been interested in the topic have had resources such as Jill Derr’s Women of Covenant: A History of the Relief Society, a study supported and endorsed by the highest church leadership—yet the general membership will not have read through its hundreds of pages. Instead, this essay offers a good starting point to understand the rich history of women in the LDS church.

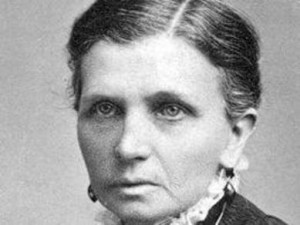

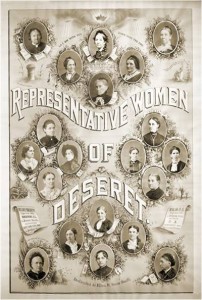

Emmeline B Wells, the fifth president of the Relief Society and the president who oversaw the time period when the great bulk of women’s healing and blessing rituals were taken away, wrote that “History may not have preserved it all, there may be no tangible record of what has been gained, but sometime we shall know that nothing has been irretrievably lost.”[viii] This essay provides newly legitimized space for me and others to continue our research into early Mormon women (without the threat of local leadership disapproving). The essay de-stigmatizes these topics and grants permission for all of us—and for the general membership at large—to engage in discussions that were all but absent in most LDS congregations. To me, all these are very good things.

[i] Susa Young Gates (daughter to Brigham Young) wrote that “The privileges and powers outlined by the Prophet in those first meetings [of the Relief Society] have never been granted to women in full even yet . . .” In Newell, Linda King. “Gifts of the Spirit: Women’s Share.” Sisters in Spirit, edited by Maureen Ursenbach Beecher and Lavina Fielding Anderson, 80–110. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992, pg 116.

[ii] Joseph wrote in his private journal (“The Book of the Law of the Lord”) about female healing and authority after he taught them during the fifth meeting of the Relief Society: “gave a lecture on the pries[t]hood shewing [sic] how the Sisters would come in possession of the privileges & blessings & gifts of the priesthood & that the signs should follow them. Such as healing the sick casting out devils &c. & that they might attain unto these blessings. By a virtuous life & conversation & diligence in keeping all the commandments.” In Bushman, Claudia Lauper. “Mystics and Healers.” In Mormon Sisters, edited by Claudia L Bushman, 1–24. Cambridge: Emmeline Press Limited, 1976, p12.

[iii] On February 20, 1890, Patriarch Benjamin Johnson of Tempe, Arizona, blessed Susan Elvira that “health and peace shall drop from the ends of thy fingers, and consolation and Comfort from thy lips. We ordain thee and set thee apart as a Nurse and as a Midwife, and thou shalt administer peace and comfort to the afflicted. The sick shall rise up at thy touch, and sickness and death shall flee away from thy presence.” In Stapley, Jonathan A and Kristine Wright. “Female Ritual Healing in Mormonism.” Journal of Mormon History 37 (Winter 2011): 1—85, p22.

[iv] There are far stronger evidences for women holding the priesthood than the word “ordain.” Women were connected to the power and authority of the priesthood, if not to office in the priesthood, in far more tangible and concrete was than women are today. For instance, consider the language in Zina D H Young’s patriarchal blessing in 1850: “the Priesthood in fullness is & Shall be Conferd upon you.” In Newell, Linda King. “Gifts of the Spirit: Women’s Share.” In In Sisters in Spirit, edited by Maureen Ursenbach Beecher and Lavina Fielding Anderson, 80–110. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1992, p116.

[v] Eliza Snow asserted that women who participated in ritual healing and blessing should be endowed, while President John Taylor saw healing and blessing as a manifestation of the faith of any member, endowed or not. In September of 1884, Eliza wrote and sent a letter that underscore the importance of the endowment and the responsibilities of women who had had it to heal and bless their communities: “Any and all sisters who honor their holy endowments, not only have the right, but should feel it a duty, whenever called upon to administer to our sisters in these ordinances, which God has graciously committed to His daughters as well as to His sons; and we testify that when administered and received in faith and humility they are accompanied with all mighty power. In as much as God our Father has revealed these sacred ordinances and committed them to His Saints, it is not only our privilege but our imperative duty to apply them for the relief of human suffering. We think we may safely say thousands can testify that God has sanctioned the administration of these ordinances by our sisters with the manifestations of His healing influence. . . .Thousands can testify that God has sanctioned the administration of these ordinances [of healing the sick] by our sisters with the manifestations of His healing influence.” In many sources, including Stapley, Jonathan A and Kristine Wright. “Female Ritual Healing in Mormonism.” Journal of Mormon History 37 (Winter 2011): 1—85, p37.

[vi] The endowment of priesthood power for women outside of the temple was implicit in that woman having received her endowment in the temple. On Jully 28, 1843, the patriarch Hyrum Smith blessed Leonora Cannon Taylor: “You shall be blesst [sic] with your portion of the Priesthood which belongeth to you, that you may be set apart for your Anointing and your inducement [endowment].” D. Michael Quinn discusses this at length in relation to the Annointed Quorum. In Quinn, D. Michael. “Mormon Women Have Had the Priesthood Since 1843.” In Women and Authority: Re-emerging Mormon Feminism. Salt Lake City: Signature Books. 1992, p366-69.

[vii] Even when the acceptance of women sealing blessings (rather than confirming them) was waning, women were still taught they held the priesthood in conjunction with their husbands: President Angus M. Cannon told the Women’s Exponent that “Women could only hold the priesthood in connection with their husbands.” He also said, “The sisters have a right to anoint the sick,” but then warned women to be “careful how they use the authority of the priesthood” in such administrations.” In Evans, Vella. “Woman’s Image in Authoritative Mormon Discourse: A Rhetorical Analysis.” PhD diss., University of Utah, 1985, p133.

[viii] Feb 20, 1902. In Derr, Jill Mulvay, Janath Russell Cannon, and Maureen Ursenbach Beecher. Women of Covenant: The Story of Relief Society. Salt Lake City: Desert Book Company, 1992, p223.

Thanks. I am overwhelmed and conflicted and appreciated your stable thoughts. I would love to hear more from you

Thank you, Cat. I am very pleased that you found my response helpful. I know what it is like to be overwhelmed and conflicted as well, so it’s nice to be thought of as stable!

Northwest Pilgrims has asked me to speak at their conference this spring, so I will be there to present the history of Mormon women blessing and healing in a large session as well as a discussion of actual stories and journal entries of early Mormon women’s personal experiences in a small session. If you’re near Seattle you should consider coming.

Nice response. I was particularly struck by this statement I the essay:

“Neither Joseph Smith, nor any person acting on his behalf, nor any of his successors conferred the Aaronic or Melchizedek Priesthood”

This is an unfortunate, blatant historical inaccuracy: Devery Anderson’s temple trilogy clearly documents primary sources of female conferral of “the fullness of the Melchizedek Priesthood” from Joseph Smith down to Heber J Grant at least. Anyone remotely aware of church history and women in the priesthood should know this.

Excellent piece, Fara! As always, I love hearing your thoughts and insight on these topics. It is such a talent to be able to write something so deliberate and articulate that thoroughly, faithfully and positively addresses many points in the Church’s essay with which you disagree. Bravo! The gospel and women’s roles in the gospel are so much bigger than the Church’s essay makes it seem. So much love to you!

Not only the essay glosses over the Anointed Quorum, but it doesn't even mention the crowning ordinance of the second anointings when women did receive priesthood offices.

Excellent response my sweet friend! I love your poetic words.

Miss our monthly conversations, Fara. This recalls to times before I felt ‘authorized’ to exercise ‘gifts of the Spirit’ such as healing, revelations, and prophecies. Why did I have these experiences, feel these powers when they so clearly in the nineteen fifties through the eighties belonged to my priesthood bearing spouse? Ideally ‘Ordaining’ and ‘setting apart’ give confidence and increase faith in what the Holy Ghost calls us to experience. I’m grateful the Priesthood leads many men where they otherwise dare not go, what they may feel is a woman’s field. But within the Priesthood they are included in healing, nurturing, counseling, caring for the poor. The Priesthood invites men to join us in the internal affairs of the human family. Women, make room for them, but don’t leave the room.

Antonio Trevisan Teixeira,

Yep. Disappointing.