America long ago fell in love with an image. It is a sacred image, fashioned over centuries of time: this image of the unharried, unconcerned, gladulatory, simple, rhythmical, amoral, dark creature…It was created, and it persists, to provide a personified pressure valve for fanciful longings in American dreams, literature and life…

– Lorraine Hansberry, The New Paternalists

CW: use of the N-word

Time in regards to the past has functioned in differing ways for black and white people. In his work Black Skin, White Masks, Fanon notes, “the disaster of the man of color lies in the fact that he was enslaved. The disaster and the inhumanity of the white man lie in the fact that somewhere he has killed man.”[1] The history of Whiteness has been destructive, systematically erasing the Other often in the interest of self-preservation. Black being often finding itself as the destroyed. While reading the excerpts from The Prophetic Imagination and Black Skin, White Masks, I found myself wondering about the place of the past in regards to the utterance of prophesy. How does the past engage with the prophetic? Should there be a relationship between the two? Though Fanon and Bruggemann do not explicitly address time, their works reflect the curious relationship between prophesy and the linear progression of “history”. In Bruggemann’s embrace of the past and Fanon’s aversion to it, the task is then to challenge the significance of past symbols in order to create a prophetic vision which uplifts all.

Fanon begins “By Way of Conclusion” with a seminal quote by Karl Marx; offering the reader a glimpse of the role of the past. Fanon echoes his sentiments throughout the chapter by outlining his position on the place of history in relation to whites and the man of color. His sweeping narrative intertwines the misconstructions of blacks and whites in order to inform his sense of self and praxis. Fanon refuses to encompassed by the Negro or white past, solidified by misconceptions of both. As a man of color, history bars him from having objectivity towards his own being. Arguably, this is reflected in the history of whites as well. Fanon also notes the stagnation accompanying the creation of a middle-class society, a society which he deems “rigidified in predetermined forms, forbidding all evolution, all gains, all progress, all discovery.”[2] This adds to the problem of sacralizing history in adhering to past traditions that prohibit growth. It is not the past that one should hope to resurrect in efforts of resistance, but rather, an awareness of the suffering that exists in the present. Fanon makes clear of his wishes of the existence of the Negro beyond what history, however, this fact does not amount to resolving the issues of today.

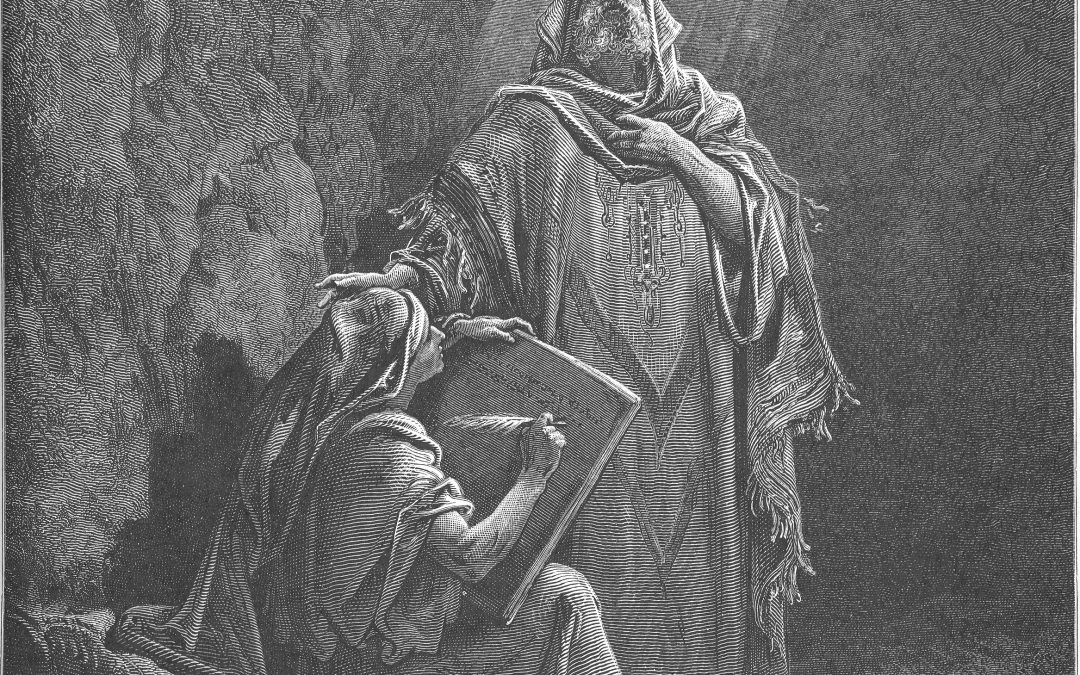

Bruggemann observes the actions of the prophet and the visions of the future in The Prophetic Imagination. “The Alternative Community of Moses” critiques the dominant culture as one which he argues is “organized against history”[3], preoccupied by what can and will be experienced in present time. Furthermore, due to the nature of the consciousness this culture maintains, its current state is perpetual. To speak to the prophetic, one must create a consciousness which counters the predominant narrative. Bruggemann points out the fallacy in solely relying in prophets as “fortune tellers” as much as they connect a potential future to what is happening in the present. To resist this dominant consciousness, an alternative consciousness must be produced. The prophetic tradition of Moses serves as a model for the alternative community needed to deconstruct this dominant culture. Moses’ vision for the Israelites was a stark contrast to the existing Egyptian hierarchal structure; a “reality” based in oppression and the interests of those in the highest positions of authority. The empire’s claim to reality was fashioned to maintain its own existence through the presence of a static god. The Israelite’s god challenged their immobile “reality” through the freedom found in its sovereign nature. The community established from Israel’s emergence from Egypt is based in the parallels drawn between Yahweh’s freedom and norms based on the historical covenant made between Yahweh and the sons and daughters of Jacob. The role of the prophet is to disrupt the oppressive order and its claim over “reality”. In order to sustain its perpetual existence, the dominant culture must project the appearance of wellness. The pronouncement of grief, then, plays a crucial role in identifying that this “reality” is not a reality which is nurturing and beneficial to the community or the self. The politics that distinguish Egypt’s reality and that of Yahweh is the difference between exploitation and empowerment, or as Bruggemann suggests, “energizing.”[4] Energizing the community brings on a sense of hope unavailable within the dominant culture. Bruggemann continues on with his hypothesis in “Prophetic Criticizing and the Embrace of Pathos”. The dominant culture (and those who sustain it) found in the “royal consciousness”, as Bruggemann outlines, is concerned in removing the concept of death within its framework. The “end” proves to be detrimental to the royal consciousness, as it would any living thing. Bruggemann notes the lack of any symbolism of death found in the royal consciousness, as it reveals an experience beyond that which upheld by authority. Doing so reveals God and God’s “reality” as the final authority in our Being, opposed to the “reality” proposed by the dominant culture. Through the offering of symbols, the public expression of fear and the reality of death, the prophet is able to counter the royal consciousness through “the language of grief”. Bruggemann details the life of the Old Testament prophet Jeremiah as an example of the expression of the language of grief and proponent of the alternative community.

Per usual, Fanon’s work was a thick read in both its complexity and nature of the subject. Nevertheless, his observation on time (in regards to the past and its relation to the present and future) warranted a closer examination on the basis of current events.

The “image”[6] Hansberry refers to in the quote offered in the beginning is solidified in American culture by the resurrection and recycling of stereotypes and tropes throughout the passing generations. The term ‘nigger’ embodies this process in its prevalence in modern American discourse. One may ask, what would America be without the concept of the ‘nigger’? Even more, what would the Black man, woman and child be without its creation? The word has been entrenched in the American consciousness to the extent that a ritual has been created out of it, in the enslavement, killing and subjugation of black people. In the interconnectedness of culture and religion (and lending itself to biblical interpretations of good versus evil), this image works itself into theological concepts of ‘black’ and ‘white’. Biblical prophesy surmises good will win out in the end (at least, according to John the Baptist). This good has been conflated with white supremacy in prophesy, biblical imagery and use of the bible. We see its manifestation in frequent connections made between the settlement of North America by Europeans and the conquest of Canaan. The actions of both were justified within their respective groups by the creation of the Other. Prophesy, in the context of conquest and domination, favors the group which effectively marginalizes the opposite group.

White supremacy created the ‘nigger’ and Black people have been engulfed by its implications. This where I come to an impasse with Fanon in regards to constructions of the past. In order for it to lose its meaning, it has to be desacralized by both white and black people. However, it maintains its status as part of Bruggemann’s “royal consciousness”. As Bruggemann offers, “we need to ask not whether it [alternative consciousness] is realistic or practical or viable but whether it is imaginable.”[7] Can America imagine itself without the swinging bodies in the poplar trees? Unlike Fanon, Bruggemann heavily relies on symbols of the past. Fanon revokes the past as a remnant of the accumulation of broken symbols. America relies heavily on these symbols. For a shift to be realized, we must turn to Bruggemann’s hypothesis on the recognition of death. The dominant culture will sustain itself on the belief that the consciousness which lies within it always was and always will be. This has meant death for black and indigenous people and in many ways, white people. For blacks, death has been found from the lynching tree to the pulpits of our grandmothers’ churches. I strongly believe that order to create the alternative community in America, it must recognize death in its dominant culture subsequent theology. For blacks and whites, “both must,” as Fanon suggests, “turn their backs on the inhuman voices which were those of their respective ancestors in order that authentic communication be possible.”[8]

The illusions of the past, the actual present and potential future intertwine with one another to create our “now”. The alternative community is the rejection of the first, recognition of the second and acknowledgement that the third is possible. Are we ready to embrace all three?

[1] Frantz Fanon. Black Skin, White Masks. (Grove Press Inc: 1967). 231.

[2] Ibid. 224.

[3] Walter Bruggemann. The Prophetic Imagination. (Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 2011) 1.

[4] Ibid, 9.

[5] James Baldwin. “Faulkner and Desegregation.” The Price of the Ticket: Collected Non-Fiction, 1948 – 1985. (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985). 148-149.

[6] Lorraine Hansberry. “The Drinking Gourd.” Les Blancs: The Collected Last Plays: The Drinking Gourd/What Use Are Flowers?. Ed. Robert Nemiroff. (New York: Vintage Books, 1972). 155-156.

[7] Bruggemann, 39.

[8] Fanon, 231.

You wrote:

“The prophetic tradition of Moses serves as a model for the alternative community needed to deconstruct this dominant culture. Moses’ vision for the Israelites was a stark contrast to the existing Egyptian hierarchal structure; a “reality” based in oppression and the interests of those in the highest positions of authority. The empire’s claim to reality was fashioned to maintain its own existence through the presence of a static god.”

Do you believe Mormonism can reclaim this?

The key Mormon passage on these subjects is Moses 6:45-46 in the Pearl of Great Price, as follows:

45 And death hath come upon our fathers; nevertheless we know them, and cannot deny, and even the first of all we know, even Adam.

46 For a book of remembrance we have written among us, according to the pattern given by the finger of God; and it is given in our own language.

In other words, death hath not come upon our mothers, and we never knew them, because they never lived; the patriarchy erases them altogether from the book of remembrance. Only the “fathers” count.