As a therapist, I sit in a chair and talk with people about their journeys in this life while they lie on the couch in my office. Sometimes my clients contemplate life. Sometimes they contemplate events. I’m often asked, because I practice in Utah, if I’m a Latter Day Saint. Sometimes I answer yes. Sometimes I don’t answer. My new approach is to say that I’m “very familiar with the LDS religion” because I appreciate boundaries and also, I’ve had a realization about the nuances of answering “yes” to that question.

People – complete strangers, really – only ask me if I’m LDS when I’m in a position of authority over them. My students will ask in class and my clients will ask in session. It has a leveling effect and I’m keenly aware of that. It makes me “ok.” It aligns me with an assumed subset of thinking, particularly in Utah, about how I’ll listen and how I’ll speak with my clients about the issues of most importance to them. Of course, there’s also the ease of not having to do as much code-switching between LDS and non-LDS when my students and clients know that I’m LDS. That isn’t lost on me either. However, it has begun to present challenges for me that I’m only beginning to unpack.

Is it because I’m a therapist?

Every therapy session I have is a multi/cross-cultural session just because I’m in the room and decided to come to work today. I don’t have to do anything extra. In an attempt to join with me, my clients will initially ask about my religious background and I often wonder if it’s because I’m probably the first black therapist they’ve worked with and maybe the first black person with whom they’ve had a sustained interaction. And not just any interaction, a “My mom forgot about me and I realized it when I was 5 and that’s why I can’t send her a mother’s day card” interaction. I get to see people’s insides and their religious identity is part of those insides. I also wonder if it’s because I’m in that position of power, that they’ll ask if I’m LDS in order to put me in some kind of place – either the acceptable black person who joined the True Church and isn’t all “hung up” on race issues in or outside of the church. Or that I’m the black member of the church who converted later in life after fulfilling myriad stereotypes about blackness in general and black womanhood in particular. These assumptions make themselves manifest in the kinds of questions I’m asked about my experience, my experiences, and my personal life that I’m not sure if my non-black colleagues receive or if my non-black pediatrician or dentist receive them as well. There’s this feeling of being under a microscope for more than the hesitancy of a client feeling stigma for “talking to a therapist.” Stereotypically, Mormons are conditioned to confess their emotional guts to complete strangers. I’m just not a man in a position of authority where this is the norm because I sit at a desk with a picture of Jesus kneeling in Gethsemane behind me.

Is it because I’m a black woman?

I know that my clients seek to level me with them, I wonder what the unconscious dialogue is within their minds, “You may be my therapist and putting my insides under a microscope, but you’re LDS just like me, and you’re a black LDS person, so doctrinally, I’ve got the up on you because I’m not black and I obviously haven’t read the Race and the Priesthood essay.” Do they dislike them being where they are and me being where I am? Do I join the club of “not having it all together” because I’m LDS too? (Totally possible.) But it’s this idea of joining a club only within my professional capacity that strikes me as interesting. Do I want to be part of the club because of a power differential? Do I get the same benefit of the doubt when I’m not in a professional capacity? Do my clients see me and say, “wow, we’re different. How will she ever understand my plight? She hasn’t lived my life and I’m supposed to spill my guts to her? Hmmm, I wonder if she’s LDS.”

And so the questions come.

Similarly with my students, when I speak up as an Ally for equitable treatment around sexuality and gender in the classroom. My LDS student ask if i’m LDS. They ask how I reconcile what I believe with the work that I do? I’ve told them repeatedly that if I’m wrong and going to hell because of my politics, I’ve completely accepted it and have arranged for friends and family to do missionary work in outer darkness if they can find me since I’ll be white when I die.

Is it both?

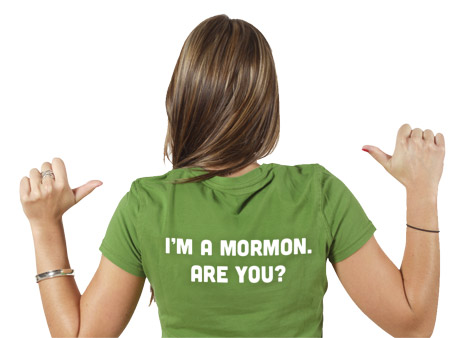

Are you LDS?

What if I am? What if you are? Why is it, in this circumstance, where I’m in a position of advantage by virtue only of education – that my sameness to you matters? What makes me more (or less, at times – but not often, more on that in a minute) acceptable to you if I’m LDS? Why is that the checkbox for the green light?

There are times where I know that when I’m working with people who feel they are on the outside of being LDS, that my being LDS can be a blessing and a challenge. A blessing because I know what it is like to be LDS and on the outside, just because I breathe oxygen in brown skin. A blessing because I know that people don’t automatically assume that I’m LDS when they look at me, so they have to ask. A blessing because I know that I can and do have to watch my language because of how easy it is to align with other members and help them let their guard down, yet simultaneously, put themselves in a place of comfort where they may not truly challenge their world view because they believe that I share it with them. And at times, my membership can pose a challenge, for both my clients, my students, and myself, because I’m still an active member of the Church and I’m a woman of color. My clients and my students who are not people of color, yet are experiencing oppression and exclusion, seek to align with me in solidarity of oppression as they consider leaving the church or speaking up and speaking out. They believe that we have much in common because they are having their awakening while I live in a perpetually awakened state of blackness in Mormonism.

It’s an interesting road to walk, because, as a therapist, the process can never become about me. It’s a therapeutic no-no. Still, it does not provide protection for my experience at the sake of my client’s and the traumas that happen to me when I experience micro-aggressions in session have to be processed elsewhere. When I’m out-privileged by white males in an emergency situation while attempting to advocate for a client’s needs, I’m aware that none of the men in position to help asked me if I am LDS. Even though I was the professional concerned about a client’s situation and responsible to report it. “Oh, but LaShawn, you can’t be so sensitive. They had a job to do.” So did I. And to be silenced in the face of my professional abilities and education when it was actually needed most is a feeling that I can’t properly explain in words.

Of course, I have no reason to believe that any of this is true or that my faith in my profession has any semblance of power. Despite a client here or there who makes inappropriate comments, I just go to work and do my job. I did have a client who chose me because they “hated Mormons and knew everybody else was Mormon when they saw their pictures, and then they saw me and knew they wanted to be with me because I wasn’t Mormon.”

Based on a picture.

Well, thanks. I think?

Still, it’s my ethical (but not really my ethnic) duty…

I notice that I consistently have to position myself within my Mormonism and my blackness to best make connections with my clients so that they can trust me and believe that I will get where they are coming from if their concerns are religious in nature, especially. From faith crises over excommunciations, to struggles of working through a past of polygamy, to grappling with gender roles, and sexuality, and the Church’s stance on both causing tension with my client’s lived experiences, I’m expected as a fellow saint taking notes on my clipboard to start where my client is, in this position of Mormon-ness as they define it. It is not easy. It comes with the territory, though, just like being a black member of the LDS Church. I experience ongoing litmus tests about what kind of member I am and how worthy of a member I am and what that means about the kind of work and success that I can have with other Members who request counseling services.

This means that I prepare myself to witness their indignation at being lied to and lied about, dismissed and devalued, ignored and misrepresented for not fitting into the mold that was created for them. This means that even from my position of power, I feel simultaneously removed to a place of “not-as-powerful” because of my shared religious background with some of my clients. I’m forced into equality on their terms so that they feel comfortable displaying their emotional guts. My professionalism, in some ways, is removed each time I confirm my religious identity because of the underlying understanding of what I must prove in order to maintain their trust.

It could be stereotype threat. It could be legitimate. Whatever it is, the fact that I have to question my invitation to access the “you’re okay because you’re just like me, religiously” club has its jarring moments. And it keeps me cognizant of my double (triple? quadruple?) consciousness as a person, a woman, of color, and a professional in a position of debilitating power for myself, my clients, and my students, all from the mere question, are you LDS?

Thanks for the insightful and personal post. Our modern, secular world is certainly adept at slicing and dicing us into fragments – a lot of input from a lot of sectors; a high-volume psychological and spiritual SuroundSound, if you will. If you haven’t done so, I recommend reading Berger and Luckmann’s, The Social Construction of Reality. Fascinating stuff. Stick with the Church. Its truths will last. For me at least, the Where-did-we-come-from-why-am-I-here-what-happens-after-death aspect of the Gospel provides both coordinates and solid footing for the mortal tug-of-war. And we are promised that one day we will, the lot of us, see “eye to eye” on reality. I think you will be out of a job then.

Fascinating post, thanks for sharing your experience and perspective. Definitely something to think about.

Really interesting article! When I was active, I did choose Mormon therapists and psychologists because of a fear of them wanting to talk me out of my beliefs. That’s the only reason I’d have asked if a psychologist was mormon, but it’s interesting to contemplate how race and the church has complicated your interactions with clients. Thanks for this perspective.

I have found it’s easier, professionally, to tell people in the ward or friends in the Stake that I don’t work for family or Church members. So many slippery slopes and risks to the relationship that span beyond the business doors. I feel everyone is more comfortable and don’t feel pressure from me to “get their business” because I don’t want it! The few times I have broken this rule, I have regretted it. Best to keep money far, far away from church relationships.

Also, that being said, realizing a doctor/therapist WAS LDS and a friend of the in-laws at that after many appointments where I spoke openly and refreshingly “free” of trying to fit a mold (part of the problem in the first place), resulted in immediate detachment, despite me saying out loud to her that “No, no, it’s ok.” I was lying through my teeth. Who can you trust when you know people talk?

I loved this article. If I needed to have therapy, I would come to you, despite the fact that I don’t live in Utah.

It’s refreshing to read this sort of article. As a white person, now out of the church, I feel restricted when talking about race in the church or out of the church. I have a fantastic niece-in-law that is black, and I think it always has underlying affects.

Thanks for your honesty and candor.