Sometimes you read a book that challenges you to your core and begins to shift your paradigm. The Peace Giver, by James Ferrell has become one of those books for me. I’m on my 2nd time reading it in the course of a week. I’m sure that many people have read it and have been similarly impacted,and if you haven’t – I’m going to suggest that you consider it, if for nothing more than expanded perspective.

As a therapist, I sit with clients who question everything that isn’t lining up in life the way they thought it should, would, or could when they did everything they were supposed to do. Are they, can they be, saved? Do they even want it at this point? What, exactly, is grace?

These are the same questions I sit with myself when I’m not the one sitting in the office chair holding a notepad, asking reflective questions, and reaching into silence.

The Peacegiver made me question everything I thought I believed about the Atonement while giving me space to question the magic bullet he offers about the Atonement. You might say, as I did – but isn’t the Atonement the magic bullet? I believe that it is. I also know that I sit with clients who feel like the Atonement is a sucker punch, “If you really believed in Christ, you’d forgive…. You’d repent…. You’d be over it by now.” “How can you withhold from God the commandment to forgive? Is the Atonement not good enough for you?”

Ouch.

It’s hard to reconcile with the atonement when you feel like it’s a backhanded compliment, a wind-up for a punch, or a blind-sided, passive aggressive, lovingly packaged guilt trip – especially when it comes from well-meaning and well-intentioned people who say that they love you and just want the best for you. Ferrell does a little bit of that in his book’s characters and even still he continues to make pretty compelling arguments as to why he might have a point beyond sounding like he’s trying to clobber someone with the Atonement.

I see people struggling to find how the Atonement works, specifically, for them as individuals with complex life experiences. The “one-size fits all” answer at these moments is insensitive at best. The atonement needs to become a multifunctional article of clothing that my clients can alter and stitch, and adjust to their specific needs. I agree with them. I believe that the Atonement is an individual process, like prayer, and personal revelation. You don’t only work out your own salvation with fear and trembling, you work out prayer, personal revelation, and the atonement too.

I sit with clients as they wrestle through their mortal existence as an Intelligence and their understanding of life in this human form. I sit with them as they reflect on whether or not God really hears them, whether God really answers prayers, whether God really cares, and whether something is wrong with them for not feeling the Spirit or receiving answers the way it’s written in scripture and discussed over the pulpit.

“My bosom never burns after I pray, but when I’m camping under the stars at night…”

“I never hear a still small voice after I pray, but when I’m in solitude after organizing my office space or meditating or updating my planner…”

My clients are learning to hear the Spirit speak to them. So I sit with them and I listen with them.

When my clients are trying to wrap their brains and their hearts around the Atonement and the need, desire, and commandment to repent as well as to forgive – and especially to forgive – I’m now reminded of the Peacegiver as much for them, as for myself.

One of the major takeaways from the book that I have started to weave into my work with clients struggling with elements of faith (in and outside of the LDS Church) is the way that the Atonement is an exercise in mindfulness.

Often, my clients want to forgive and be done with it. Repent and be done with it.

Because that’s what the Atonement was, right? An event that was eventually “finished.”

Okay, a series of events. But they were finite events. They had a beginning, a middle, and an end. We can cite the verses where it starts and where it ends (and the meanderings of others in between). But essentially, we receive the atonement as such:

- Christ suffered in Gethsemane – an event, a couple of hours, friends fell asleep – check.

- Christ suffered on the cross – an event, another couple of hours – check.

- Christ was resurrected 3 days later – as an event, a glorious one at that – celestial check, band plays, and angels sing.

The Savior overcame and we can too! But when? Good question. So often, my clients wonder where is their resurrection? It’s been way longer than three days. When do they get to overcome the events that they feel they atone for again and again? Where is their peace?

It’s not in therapy – at least not as a finite series of events. I am starting to see it in therapy as a mindful process. It’s also in relationship – ongoing healthy interaction – with the therapist, and this, too, is as a mindful process. It’s in understanding that while the Atonement seems like a series of finite events when we read about it, maybe that’s because we read about it and haven’t figured out the way to see and experience living it in our own particular way.

Maybe the Atonement, too, is really a mindful, ongoing process of being in healthy, individual, “the worth of a soul is great in the sight of God” relationship with the Savior. Maybe it’s through the mindful application of the Atonement to our lives that it becomes an ongoing and refining process for each of us.

What is this mindful application process? Well, I’m still figuring that out through trial and error with myself as well as my clients. What I do know is that it begins in gaining the ability to recognize what’s going on in your heart as you experience life’s moments. As you consistently recognize what’s going on in your heart, moment by moment, you will recognize feelings of war with ourselves or with/toward another person* – that’s mindfulness: the ability to simply recognize that you’re having feelings.

When you recognize yourself having feelings or being at war – whether it’s toward yourself or toward another person – that’s when you are starting to have just enough space between feeling and reacting in order to create a more balanced response which includes turning to Christ’s atoning work. In turning to his work, you then choose to give the feelings and the situation to Him so that he can influence your response.

This is mindfulness, simply slowing ourselves down enough to recognize our feelings, and slowing our thoughts down to help us begin to understand our feelings in ways that allow us to respond instead of react.

This is mindfulness, slowing down just enough to be curious if Christ can take it for us or carry it with us instead of taking it upon ourselves. And this is what transforms the atonement from a blind-sided sucker punch to a growing partnership between two individuals – One who has been through it and one who is going through it.

The Atonement becomes a process of mindfulness because as humans, we seem to forget the effect of finite events. We would learn from them more consistently in ways that would influence life altering change if we were a little more mindful. But because we aren’t there yet, we seem to need ongoing reminders that God expects us to fumble our way through free agency and be harmed as other people fumble their way along, too. And so we have the challenge of stepping into moment-to-moment-turn-to-the-atonement opportunities by how we respond to experiencing harm. (Note: this is not about “not choosing to be offended” this is the reality of being hurt by someone’s offense and choosing the Atonement as it works for you in partnership with Christ.)

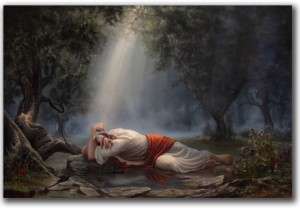

To share with you how real this was for me as I read, imagine yourself feeling shame about who you are or being wronged by another, and turn yourself to see a kneeling, agonizing, and praying Christ in Gethsemane. Then say to him, in effect, “Here’s another one, even though I know you’re already suffering.”

And just feel that moment.

It is intense beyond the power of my capacity for human language to explain what it takes to imagine, let alone, commit to acknowledging a sin that either I’ve committed or that someone is committing or has committed against me and casting it into Gethsemane with my Savior. I’ve used this picture before, and I’ll use it again – because this is what kept coming to me as I read the Peace Giver.

Why would I give you more, Lord? That’s what I asked as I read through the initial chapters. This “more” is exactly what I explore with my clients (in and outside of the church) as they psychologically and emotionally wrestle through life.

It is hard to let go of that feeling and that experience. It is hard to give something so wrong to someone who didn’t commit the wrong and has suffered already for the wrongs others committed. But what’s your alternative? Commit harm yourself in reaction to how you’re feeling (either toward yourself or another person) and then have to repent for it or, in reality, rationalize why you harmed and then eventually repent. And repent. And repent some more on the way toward healing.

The bottom line seems to be that we’re going to be using the Atonement either way. To do so most effectively, we might have to start the Atonement process when we are still in some sense of control of it (based on how we understand it) by finding ways to access it before we use our agency in a harmful way.

And this is the helpless feeling of the sucker punch.

We cannot get through this life without the Atonement. But so many times we want to do it on our own and just not need the Atonement. We can get it right on our own with minor mistakes here and there, can’t we? Really, does God want us to be weak and dependent people? Is he forcing the Atonement on us? It feels like that for my clients who battle through perfectionism’s favorite tool: control.

I’m not sure that this is the answer or the implication, though I understand the sentiment. Instead I think it’s that God wants us to learn to lean on strength by recognizing when and how to ask for help. The Atonement is that help. It is before us, helping us to reconsider a decisive action to harm when possible and it is behind us, helping us clear away harm when inevitable.

It is not, and cannot, be an event.

Ever.

It must be a process… a mindful process of remembering our agreement and developing our relationship with Deity by developing ourselves into carriers of peaceful hearts.

How do we become mindful enough to lean on the Atonement in the moments when our hearts want war with words, grudges, actions, and inaction? We recognize that there may be much more to the statement, “Father, forgive them, for they know not what they do.” And maybe it wasn’t just for the Roman soldiers nailing our Savior to the cross in that moment. I’m coming to believe that it was for the friends and family of the Savior who felt war as they watched harm being done to Him. It is, then, for us, too, as we wrestle and war in our hearts against one another. We know not what we do while we are at war. We know best what to do when we are at peace and sustained by our Partner.

We reach toward peace when we begin the process of gaining a mindful and intentional practice of incorporating the power of the Atonement into the moments of our lives. But don’t take my word for it, read the Peace Giver.

*read the Anatomy of Peace. The author of the Peace Giver is affiliated with the folks from the Arbinger Institute who write along much of these same lines.

I really like the Arbinger Model. I have read all the books and hung out at their forums. I even own the Peacegiver, and note many of the ideas you wrote about. By the way LaShawn you have a beautiful writing style.My struggle comes in the conviction that there is/was an atonement. I love the idea of one. I sorrow greatly when I imagine it’s possibilities. I feel horrid regret when I add to it or feel that my existence opened the need for it. From those thoughts alone, I shrink from an Atonement. Because either way I, just me being born, caused an innocent soul extreme suffering.

I do try, because of Arbinger, to live more wisely to be mindful. I look for my intent in things, hoping to be less collusive and more genuine. To treat people as people and so on.

I appreciate the reminder of mindfulness and hope someday I can look at the Atonement as hopefully as you do.