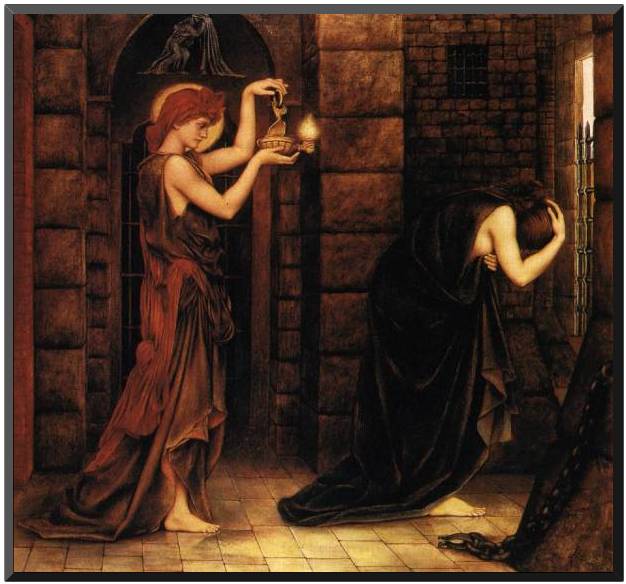

Hope is inspiring. It expands our hearts and lifts our mind. It pushes our feet back under our bodies to rise up and get back to work in the face of difficult obstacles. In times of disappointment, trial and depression, in the doldrums of guilt and the paralysis of weakness, hope is the liberator, suddenly appearing to spring us from our personal prisons.

But what of Hope-the-Enabler? That doppleganger responsible for squandering activity after liberation? The pseudo-messianic jailer leading us right into a neighboring cell of apathy and inactivity. Aren’t we God’s hands, eyes and ears? Why should we be content to hope that God will regulate our and humanity’s problems?

I’ve had enough of hope lately, at least as it’s been recently deployed in the face of pervasive and persistent global tragedies. “Well, that’s the the guy I voted for, and we can only pray that God will take care of the rest” (a real conversation I had).

???

I don’t think so. God gave you the vote. The consequences, we all are going to have to shoulder together.

Hope can be too personally-focused, sometimes downright selfish, especially when we hope against all personal responsibility for outlandish, irrational outcomes. In the case of the vote, we can’t hope that God will change the hearts of the elected officials we’ve endorsed, or shield their victims. That’s on us. I’m becoming more and more reluctant to accept that God should and will deliver us from any evil that we are complicit in: medical, psychological, familial, environmental, political, economic. There’s a reason God appears to help those who help themselves: with increased action comes diminishing reliance on hope, increasing the results that none of us needs to hope against! Let’s go to work instead of hoping for a deus ex machina!

***

Derrick Jensen visited Centre College’s campus this semester, peddling what I thought would be his doomsday scenarios for the natural world. Turns out, the prolific author, activist, and eco-philosopher was one of the most friendly, thoughtful, and reasonable people I have ever met! In his article in Orion Magazine entitled “Beyond Hope,” Jensen offers a definition that should make us pause before choosing hope over action in our lives:

“At a talk I gave last spring, someone asked me to define [hope]. I turned the question back on the audience, and here’s the definition we all came up with: hope is a longing for a future condition over which you have no agency; it means you are essentially powerless.

I’m not, for example, going to say I hope I eat something tomorrow. I just will. I don’t hope I take another breath right now, nor that I finish writing this sentence. I just do them. On the other hand, I do hope that the next time I get on a plane, it doesn’t crash. To hope for some result means you have given up any agency concerning it. Many people say they hope the dominant culture stops destroying the world. By saying that, they’ve assumed that the destruction will continue, at least in the short term, and they’ve stepped away from their own ability to participate in stopping it.”

This is a powerful query: how might hope be a kind of stepping away?

Now, many of us, as Mormons and Christians, are understandably reluctant to handle so roughly one of our most cherished ladies. We’re all children of St. Paul, and he seemed to put a lot of stock in Hope. The Abrahamic covenant, after all, is being fulfilled by a hope in something completely unreasonable (eternal life and progeny):

“(As it is written, I have made thee a father of many nations,) before him whom he believed, even God, who quickeneth the dead, and calleth those things which be not as though they were.

Who against hope believed in hope, that he might become the father of many nations; according to that which was spoken.”

(KJV, Romans 4:17-18)

Guaranteeing eternal lives, like flying a plane, though, is solidly outside most of our reach. But I bet a lot of the things we hope for are not. Paul grasped quite well, the limits of hope and the preeminence of her superior sister Charity, or the active life, whose most powerful treatise is not 1 Corinthians but Christ’s own words as found in Matthew:

“For I was hungry and you gave Me something to eat, I was thirsty and you gave Me something to drink, I was a stranger and you took Me in,

Naked, and ye clothed me: I was sick, and ye visited me: I was in prison, and ye came unto me.

Then shall the righteous answer him, saying, Lord, when saw we thee an hungered, and fed thee? or thirsty, and gave thee drink? […]

And the King shall answer and say unto them, Verily I say unto you, Inasmuch as ye have done it unto one of the least of these my brethren, ye have done it unto me.” (KJV, Matthew 25:35-39)

***

There is surely a time for hope (ever more brief, in my opinion). I’m becoming ever more convinced that inspired intentional engagement is the answer to most of the (often self-made) problems we face.

This is largely a discussion of semantics. No one would ever take risky action without hope, let alone faith.

“God helps those who help themselves” makes more sense when we accept that God is not separate from us. Clearly, we are limited by mortality but realization of our divine potential enables us to participate as godly beings in the work of eternity.