Note:

This is the unedited, longer version of a talk I gave in Sacrament Meeting two years ago.

Click here to listen to Jared Anderson’s podcast that goes over this lesson.

The First Vision, Polygamy, and the LDS Temple Endowment

Michael Barker

January 23, 2011

My talk is based on an essay I have been contemplating writing for over a year. When Bishop Wallace asked me to speak on whatever topic I desired, I saw it as the impetus to finally put my thoughts down on paper. The thesis of the essay, and my talk this afternoon, has been the center of many lively conversations and debates with my wife over the past year as I have tried to develop the thoughts I wish to express. It is an attempt to look at history and faith objectively and try to reconcile the two in some important way; it is an effort to be sympathetic towards both thought and faith.

“My imagined audience has been skeptics of the church and you. Today I turn my attention toward my brothers and sisters in the Church and ask for your attention. I have an urge to awaken self-satisfied Mormons to the problems we face, both intellectual and cultural; I hope some today will feel my elbow in their ribs from time to time. I desire to show the richness and compass of Joseph Smith’s Theology” (Richard Bushman, Preface, Believing History – Latter-Day Saint Essays; edited by Reid L. Neilson & Jed Woodworth, pg vii).

My talk will touch on several aspects of our religion and its history: President Joseph F. Smith (nephew of the prophet Joseph Smith), Apostle and U.S. Senator – Reed Smoot, polygamy, Moses, Islam, and Judaism. The focus however, will be around Joseph Smith’s First Vision, and the wonder and beauty of Jesus Christ’s Atonement.

I would like to do so by entertaining an enduring question that was once proposed and is the central question of my talk, “How do religious communities change over time and retain a sense of sameness with their originating vision?” (Dr. Kathleen Flake)

You can argue that Judaism’s founding vision was with Moses and Jehovah communicating at the burning bush on Mt. Sinai, his later leading the children of Israel out of captivity from Egypt, and receiving the 10 commandments. Islam’s founding vision was the revealing of the Quran in 610 A.D. to Mohammed by an angel Gabriel. Christianity’s founding vision was the crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus Christ.

Back to the original question, “How does a religious community change over time and retain a sense of sameness with their originating vision?” I submit to you, it is through ceremony.

Jews, to remember their founding vision, celebrate the Passover; eating unleavened bread, bitter herbs, the Pascal lamb, and recounting the Exodus story. Muslim’s remember Mohammed receiving the first parts of the Quran during the last 10 days of Ramadan, known as Laylat-al-Qadr, or night of power. These are the most sacred days of Islam; marked by increased prayers, spirituality, ritualistic cleansing of oneself, and at night going to Mosque and reading the Quran. For Christians, remembering our founding vision of the sufferings and ultimately death and resurrection of Christ comes through partaking of the Sacrament of the Lord’s Supper. Christians will eat bread to remember Christ’s body, and drink water or wine to remember His blood spilt to redeem mankind.

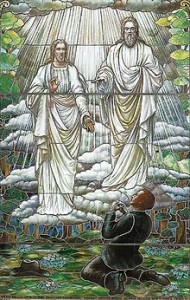

For us, who are members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, we share the common founding vision, with all Christians, if you will, of Christ’s death crowned by his Resurrection. However, we also have a founding vision that is particular to us. It is young Joseph Smith’s theophany that we now call the First Vision. But, is there a ceremony through which we retain our sense of sameness with young Joseph’s originating vision?

Joseph Smith’s first handwritten account of the First Vision, 1832, Joseph Smith Letterbook 1, pg. 3. Thank you to Jared Anderson for this image: mormonsundayschool.org

There are at least 9 contemporary accounts of Joseph Smith’s First Vision, but only 4 can we trace either directly or indirectly to Joseph himself. The Kirtland Letter Book has an 1832 version, later published in 1834. November 9th 1835, there is an entry in Joseph Smith’s Diary. James Mulholland’s Journal entry in 1838, interesting enough, is the Church’s official version which was later edited by an unknown person. It was not until 1880, on motion of Joseph F. Smith (then 1st counselor in 1st Presidency) that this 1838 account was added to our cannon of scripture. We also have the 1842 Went Worth Letter which later had excerpts printed in the Church’s periodical, “The Times and Seasons”.

All these versions have their nuances. However, since most of us are familiar with Joseph’s 1838 version, which is now canonical, it is from that account that I will reference. Joseph, in 1820, lived in up-sate New York in an area of religious fervor, known as the “Burnt Over District”. Confused about the religions of his day, Joseph went to a grove of trees next to his family farm to ask for divine help. What occurred we can read in Joseph Smith History 1: 17 “ When the light rested upon me I saw two Personages, whose brightness and glory defy all description, standing above me in the air. One of them spake unto me, calling me by name and said, pointing to the other – This is My Beloved Son. Hear Him!”

Of Joseph’s Great Vision, our past prophet, Gordon B. Hinkley said:

“Our entire case as members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints rests on the validity of this glorious First Vision. … Nothing on which we base our doctrine, nothing we teach, nothing we live by is of greater importance than this initial declaration. I submit that if Joseph Smith talked with God the Father and His Beloved Son, then all else of which he spoke is true. This is the hinge on which turns the gate that leads to the path of salvation and eternal life” (Prophet Gordon B. Hinckley, Ensign Mag., Nov. 1998, pp.70-71).

Joseph’s Theophany

For us members of the LDS faith, in the beginning of the 21st century, this great theophany is of singular importance to our history and theology. But was it always so? As it turns out no. Nor was Joseph peculiar in claiming to having a vision. Between 1783 and 1815 there are at least 32 pamphlets that relate visionary experiences published in the United States; most experienced after 1776 (Richard Bushman, The Visionary World of Joseph Smith, Believing History – Latter-Day Saint Essays; edited by Reid L. Neilson & Jed Woodworth, pg 201). We as Latter-Day Saints may be perplexed by the reports of so many visions in Joseph Smith’s time. We tend to think of the First Vision as unique. The natural Latter-day Saint response is to ask, “Were the other visions valid?”

The historian, Dr. Richard Bushman recommends, when approaching the stories of the other visionaries of Joseph’s time, a certain, “ Humility in judging the ways of God with mankind. We must leave open the possibility of others besides Joseph Smith hearing from the heavens” (Visionary World, pg 199). But the fact that Joseph fits within the cultural context of the Visionary World during the 18th and 19th centuries, does not lessen the First Vision’s importance nor Joseph’s uniqueness and call as the prophet of the restoration.

“Comparing the similarities of Joseph’s vision with other visionaries of the time, actually highlights the differences between Joseph and the host of now forgotten visionaries. Putting him alongside the others, forces on us the question of why their lives took such divergent paths. Others proclaimed themselves prophets, but did not go on to organize a church. The other 32 pamphleteer’s writings did not go on to become scripture and attract believers. People did not flock to hear the other visionaries’ teachings or pull up roots to gather with fellow believers. Followers of Joseph Smith did all of these things and more. They reoriented their entire lives to comply with his revelations. The differences are so great that we can scarcely even say Joseph was the most successful of the visionaries; taking his life as a whole, we must conclude that he was of another species…”

“Joseph Smith’s experiences can be compared to reports from the other visionaries of his time, just as he can be linked to other 19th century culture – universalism, rational skepticism, republicanism, progress, revivalism, magic, communitarianism, health reform, restorationism, Zionism, and a host of others. But no one of these cultures, or even all of them added together, encompasses the whole of his thought. Joseph went beyond them all and produced culture and society that the visionaries around him could not even imagine. Visions and revelations lay at the core of the Restoration, but the doctrinal and institutional outworks extended well beyond the limits of the visionary culture” (Visionary World, pg. 207, 211)

One might expect Joseph’s preface to the Doctrine and Covenants to be the story of the First Vision, as Mormon missionaries later handed out the pamphlet “Joseph Smith’s Own Story” to prospective converts. But judging from the written record, the First Vision story was little known in the early years. By Joseph Smith’s own account, after he returned from the grove he did not tell his own mother about the vision. The historical record does show that young Joseph did mention it to one person, a Methodist preacher.

“In the evolution of Methodist culture, the Methodists were very emotional and passionate in their early years. But as they evolved as a church they become much more respectable; there’s some wealthy people [but] it became very much a middle class church. There comes a point where the Methodists of the 1830’s repudiate the Methodists of the early 1800s. Joseph Smith was right at that hinge – where Methodism is trying to ‘poo-poo’ these type of religious expressions. The reason the Methodist preacher had a quick answer to Joseph’s question is because he faced this question all the time in his own church. He was trying to discourage this type of outburst. Joseph at age 14 was completely unaware of this type of shift in church culture during that time” (FAIR blog podcast, October 12, 2010, Interview with Richard Bushman, part I 13:40). The relating of his vision to the local Methodist preacher, who gave a negative response, must have discouraged Joseph’s further retellings.

In section 20 (received in1830) of the Doctrine and Covenants, the vision gets an oblique reference: “it was truly manifested unto the first elder that he had received a remission of his sins.” Without so much as mentioning the appearance of the Father and the Son, Joseph seemed to have made little of the revelation that connected him most strongly to the visionaries of his time.

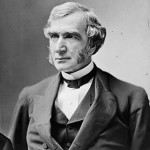

“While appreciations for Joseph’s First Vision did grow in the last decade of the 19th century, not until the early 20th century did it move to the fore of Latter-day Saint self representation” (Kathleen Flake, The Politics of American Religious Identity – The Seating of Reed Smoot, Mormon Apostle, pg 118). The turning point in the status of the First Vision occurred during the administration of President Joseph F. Smith. What was the catalyst? The seating of Senator Reed Smoot, the LDS Apostle – and polygamy.

Many of us assume the church abandoned polygamy with President Wilford Woodruff’s 1890 Manifesto that is now part of our canonized scripture. This was not the case. But why? To answer this question, we must understand how polygamy was seen by members of the church during the latter half of the 19th century.

Polygamy, Salvation, & Reed Smoot

When questioned about polygamy as a teen, I would usually say something along the lines of, “There were more women than men within the church” as the reason. This is simply wrong. Historically and Sociologically it may have been true that there were more women than men, as it was true with early Christianity during its rise in the first 3 centuries A.D. (Rodney Stark, The Rise of Christianity, pg 98). This, however, was not the reason for polygamy; this was merely a polemic in defense of it.

When polygamy was first introduced, in Nauvoo, Illinois it was only to a few members of the church. These members of the church were also the first members to whom what we now call our temple Endowment Ceremony was introduced. This group of people were known as the “Quorum of the Anointed”. This is interesting for us in the 21st century because now quorum is only used in conjunction with priesthood offices, yet this quorum consisted of men and women.

Section 132 of the Doctrine and Covenants records the revelation on polygamy. Even though this was recorded in 1843, it was not until the Utah period that the general membership of the church knew about it. There are multiple reasons why members of the church in the latter half of the 19th and into the early 20th centuries held the doctrine of polygamy in such high esteem and in turn, had difficulty abandoning the practice; I will present four.

- Just like one’s last words before death carries with it some sort of salient importance, the revelation on the plurality of wives carried the same weight. Not because it was Joseph’s last revelation, but because it was the last that the general membership had heard. This is one reason it was difficult to let go.

- Another reason polygamy was difficult to abandon was because Joseph’s revelation on the plurality of wives became canonized in the 1876 edition of the Doctrine and Covenants. This was 33 years after being recorded and twenty-four years after its publication by Brigham Young.

- A third reason has to do with the fact that its practice was seen as necessary for exaltation. For us members of the 21st century, when we read section 132 of the doctrine and covenants, celestial marriage, means marriage that occurs in the temple; binding wife, husband, and their children for time and eternity. Looking at the primary documents – sermons and personal journal entries from the latter half of the 19th century and into the early 20th century, it is clear that for many members, celestial marriage, meant polygamy; not simply being sealed to one’s spouse in the temple. Now if the government comes and tells a church that they must stop doing something that is seen by that church as necessary for their salvation, such as baptizing, or there will be consequences, what do you think will happen? The church will continue to baptize, and possibly out of public view. That is exactly what one would expect to happen with the practice of plural marriage – and that is exactly what happened. Despite the U.S. Congress passing multiple anti-polygamy legislation – the Morrill Act in 1862, the Poland Act in 1874, the Edmund’s Act of 1882, and the Edmund Tucker Act of 1887, members of the church continued to practice polygamy because, to them, it was seen as being salvific.

- This brings us to a fourth reason. When a group is marginalized and/or persecuted for a tenant of their faith, that tenant becomes that much more important and becomes the group’s identifier. The persecuted group tends to dig their heals in, retrench, and fight back.

In 1900 Reed Smoot became an Apostle of the church. In 1903 he was elected to the U.S. Senate. His election set off a four year Senate hearing, between 1904 and 1907. At the center of the controversy was Mormon polygamy and that a law breaker, like Apostle Smoot, could not be a U.S. Senator if he was a polygamist. Oddly enough, Reed Smoot was not a polygamist; he was a monogamist his entire life.

Nothing was bigger in the news than the Smoot hearing. The four-year proceeding created a 3,500 page record of testimony by 100 witnesses on every peculiarity of Mormonism. Even President Joseph F. Smith was summoned to Washington D.C. and questioned by the committee.

President Joseph F. Smith in 1904 gave what is known as the 2nd Manifesto, ending polygamy for good. A year later, on October 28, 1905, this led to the resignations of the Apostle Elder John W. Taylor (son of President John Taylor the prophet) and Apostle, Elder Matthias F. Cowley; both of the Quorum of the 12 Apostles. (Flake, pg 106) To replace them and the recently deceased Apostle, Elder Marriner Merrill, three monogamous men were presented to the church for its sustaining vote as Apostles (Flake, pg 144); one of them would later become our beloved prophet David O. McKay. Eventually in 1911 Elders Taylor and Cowley were subjected to church disciplinary courts.

To further show that the church had abandoned polygamy, Wilford Woodruff’s 1890 Manifesto was canonized in the Doctrine and Covenants in 1908. Interesting to me is the fact that it is subordinated to Section 132,which is still part of our cannon of scripture, by placement at the back of the Doctrine and Covenants. Also, interesting is that President Woodruff’s Manifesto is called a declaration, not a revelation.

What does this have to do with the First Vision? The answer to that would also be a rebuttal to the newspaper, the Topeka Capital, in 1904 when it said, “It is difficult to see, in fact, how the L.D.S. church could hope to exist and retain the confidence of its own believers after surrendering this one fundamental doctrine which differentiates it from other Christian bodies.”

An organization can withstand slow change over time, but sudden changes will cause schism. President Joseph F. Smith had to carefully negotiate the church during this time so as to not allow fissiparousness to enter into the church and break it up into smaller schismatic groups. This meant renewing the member’s confidence in the authority of our founding prophet Joseph Smith, and thereby sustaining Mormonism’s coherence with its sense of divine origin.

The Smoot hearing would, indeed, “abolish Morminism without war,” unless President Joseph F. Smith could convince the faithful that the church was  remaining the same even as it changed (Flake, 109).

remaining the same even as it changed (Flake, 109).

The situation that President Joseph F. Smith faced was much like Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark. In the beginning Dr. Jones is trying to replace a small golden figure with a bag of sand that weighs the same so as not to trigger the booby trap in the Mayan temple. President Joseph F. Smith was trying to do much the same thing. But what could possibly replace polygamy? The centennial of Joseph Smith’s birth in 1905 would prove to be the catalyst for forming the glue that kept the church together.

On December 18, 1905, President Joseph F. Smith gathered what was left of the senior leadership of the church and boarded a train for Vermont to celebrate Joseph Smith’s birth by dedicating a monument to his memory. Earlier that year, in May, property had been purchased near Joseph’s birthplace, and work was under way to find a stone out of which a 38 1/2 foot obelisk would be cut commemorating the Prophet Joseph Smith’s birth 100 years earlier. On December 23, 1905 the monument was dedicated.

“There is an interesting sociological study on collective memory that has pertinence here. Central to the thesis is the insight that commemoration is inevitably a function of selective memory and entails the equally important task of forgetting. To paraphrase, “People develop a shared identity by identifying, exploring, and agreeing on memories….In the course of taking picture or creating an album they decide what they want to remember and how they want to remember it.” In 1905 the church began to turn the American landscape into its scrap book. During President Joseph F. Smith’s administration, the church began to recover and reconstruct the sites of its early history in New York, Ohio, Missouri, Illinois, and Iowa. The Latter-day Saints felt the need for “places of memory” at the very time when they felt at risk of a breach with their past. The church’s claim to a piece of Vermont constituted a collective act of remembering that helped members forget their polygamist past they could not carry with them into the future. They would be so successful that eventually they would hardly be aware that they were agreeing to forget, and, if made aware, would tend to think they were forgetting Brigham Young, not Joseph Smith” (Flake, pg 115).

Part of the obelisk in Vermont commemorating Joseph Smith’s birth was an inscription on the base of the obelisk, on the north side; a reference to Joseph Smith’s First Vision. It was moving Joseph’s First Vision to the fore of our Latter-day Saint self-representation that proved to be so important in our new scrapbook, as it were.

“The First Vision contained the elements necessary to fill the historical, scriptural, and theological void left by the abandonment of plural marriage. To the extent that plural marriage captured the Latter-day Saint’s loyalties as Joseph’s last revelation, the First Vision, as its reference indicates, was equally appealing… It was not until 1905 that the story of the First Vision was first used in Sunday School texts, in priesthood instructional manuals in 1909, as a separate missionary tract in 1910, and in histories of the church in 1916. A grove of trees on the site where the young prophet is assumed to have received his First Vision became an increasingly popular pilgrimage site, culminating in centennial celebrations in 1920. By mid-century, The Prophet Joseph’s account of his theophany was denominated, “The Joseph Smith Story”. It becomes our touchstone for inquiry and revelation. In The First Vision, President Joseph F. Smith, found a marker of Latter-day Saint identity whose pedigree was as great as, and would be made greater than, that of plural marriage for the 20th and 21st century Latter-day Saints. Also significantly, however, the First Vision changed the arena of confrontation over differences from social action to theological belief. It placed the church at odds with other churches, not the state, and shifted the battle from issues of public morality to theological tenets” (Flake, pg. 118, 121).

Now back to the original question: How do religious communities change over time and retain a sense of sameness with their originating vision? If our church’s originating vision is Joseph Smith’s First Vision, I submit that it is through the ceremony of the Temple Endowment that we retain our sense of sameness with Joseph’s originating vision.

Much like Moses’ response when Joshua asked him to forbid Eldad and Medad from prophesying when he said, “Would God that all the LORD’S people were prophets, and that the LORD would put his spirit upon them!” (Numbers 11:12). The Prophet Joseph also had a very democratic view, if you will, of revelation and visions; he wanted all to experience what he experienced: Joseph Smith once said, “God hath not revealed anything to Joseph, but what He will make known unto the Twelve, and even the least Saint may know all things as fast as he is able to bear them” (History of the Church, 3:380). Later he stated, “When we understand the character of God, and know how to come to Him, he begins to unfold the heavens to us, and to tell us all about it. When we are ready to come to him, he is ready to come to us” (History of the Church 6:308).

The late Elder Bruce R. McConkie of the Quorum of the 12 apostles stated, “God is no respecter of persons. He will give revelations to me and to you on the same terms and conditions. I can see what Joseph Smith…saw…and so can you. I can entertain angels and see God….and so can you.“ (Bruce R. McConkie, “The Rock of Our Salvation,” Improvement Era 72, no. 12; December 1969: 85)

Joseph sought that all might experience what he had experienced in the Sacred Grove in 1820. Or to quote Dr. Kathleen Flake, assistant professor of American Religious History:

“Joseph Smith’s uniqueness can, I think, be understood by an analogy that I sometimes use to Henry Ford. Henry Ford wanted a car in every home. Joseph Smith was the Henry Ford of revelation. He wanted every home to have one, and the revelation he had in mind was the revelation he’d had, which was seeing God… So seeing God was what it was to be religious (for Joseph Smith)” (Frontline Interview, The Mormons, transcript interview with Kathleen Flake, pg 2, 24).

This brings us to the temple. If I ask members what blessings are received from temple attendance, I will hear a myriad of answers. For example, “It brings me peace. It is a place where I can receive personal revelation. I can perform saving ordinances, vicariously, for my ancestors. It is where families can be sealed for time and eternity.”

The Importance of Ceremony

May I introduce another blessing of the temple, specific to our sacred endowment ceremony?

Joseph’ Red Brick Store. It was here, in the upper level, that the LDS Endowment was first given. It was destroyed shortly after his death and rebuilt by the Community of Christ in 1980

Wednesday, May 4, 1842, after 2 days of preparation in the upper story of the Nauvoo store, the prophet Joseph Smith gathered 9 men. These men were introduced to a new set of theological instructions and ceremony (David John Buerger, The Mysteries of Godliness: A History of Mormon Temple Worship, pg 36). This ceremony introduced by Joseph in 1842 is our sacred endowment ceremony.

In the endowment ceremony, the initiates make covenants with the back drop being the story of the creation, the fall of Adam and Eve, and our redemption through the Atonement of Christ. As men and women make these covenants, they symbolically progress, the whole time seeing the central importance of Christ in the temple endowment narrative. Eventually the participants are symbolically brought before our Father in Heaven, but admittance into His presence, it becomes very apparent, is contingent on Christ’s Atonement. It is He alone that allows us to return to our Father in Heaven.

CONCLUSION

Just as Joseph saw God the Father, we symbolically are in his presence, at the end of the endowment ceremony. I submit to you, it is through the endowment ceremony, that we retain our sense of sameness with Joseph’s originating vision. Indeed the endowment helps us retain our sense of sameness with our two originating visions, Christ’s Atonement – crowned by His resurrection, and Joseph’s First Vision.

I pray that we all will make the Temple an important part of our religious expression as we see, that through the endowment ceremony, we may retain a sense of sameness with our religion’s two originating visions: the Prophet Joseph Smith’s First Vision, and the crown of Christianity’s saving message, Christ’s resurrection, even as we, as a church, change over time.

Very nice. And I’m thinking: How can a living, revalation-based religion NOT change over time? It is vital to our progression as individuals and as a church. I like the historical details you brought to this. Some new things I hadn’t heard before.

Also, because I teach youth sunday school, it’s nice to have blogs like this to keep up to date with gospel doctine discussions. Good work. Thanks for posting.

I agree 100% with your thoughts. A fun thought experiment is to imagine asking a congregation of Mormons, “How many here believe in modern revelation?” Followed by, “How many here believe in change?” My thought is that a lot more hands would go up with the first question than with the second.

I believe that revelation necessarily means change. However, in the modern church, it seems that revelation is used almost as a trope; it is used to confirm that we are right. On the other hand we have to be humble enough to realize that what we want changed might not be what God wants changed. The latter is where I struggle.