“Les Miserables has had a more profound influence on my life than anything else I have ever read other than the scriptures.” Vaughn J. Featherstone, The Incomparable Christ Our Master and Model, p. 186.

This is part II of a II part series. Part I was published on 9/18/2013, and focused on the life of Fantine.

Again, Spoilers.

As you will remember from my last post, I love Fantine’s character. She reminds me that sometimes even through no fault of our own we must make the hard choices and sometimes those hard choices are devastating. She is a tragic character in every sense of the word, and her “holiness” for lack of a better term is almost unmarred. She is the bright light in a world of darkness even when at her most downtrodden.

Jean Valjean is an entirely different sort. Jean is a reader’s dream, and a theologian’s delight. He is the gray that actually exists in the world; the gray that exists in all of us. With Fantine, her redemption is deserved on every level, with Jean we will have to wait and see.

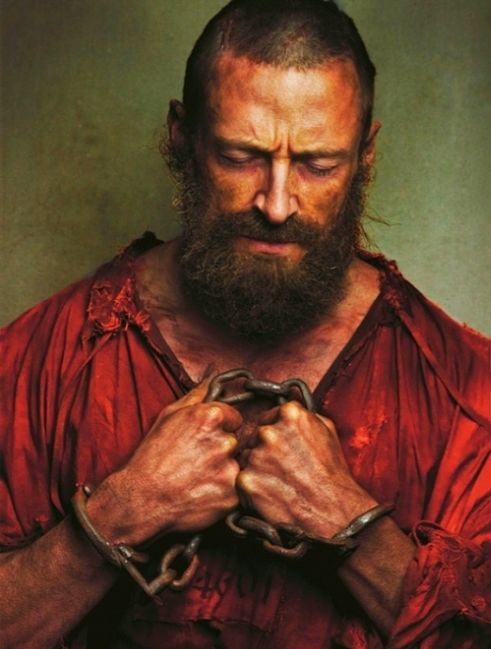

When we first meet Jean he is a prisoner (bad guy alert!, right?) Well, maybe not so much. We come to find that he has been arrested for stealing bread to feed his family members. Again, like Fantine, here is a decision made out of desperation. Can such an act truly be morally repugnant? Can it be morally justified? Jean ultimately escapes from prison and takes shelter at a Church. While at the Church he steals the good silver from the Priest. He is captured and brought back to the Church where the Priest claims that he has not stolen anything and lets him keep the silver.

Pause for a minute on that. As we discussed, Jean was initially imprisoned due to a gray area infraction. However, both the betrayal of the trust put in him by the Priest, and the actual theft itself cannot be excused can it? What of the immense act of mercy by the Priest? Is this act of mercy reminiscent of Christ’s mercy for us even when we are stupid, and selfish, and take things for granted?

Jean goes on to run a business, meets Fantine, pledges to find and care for her daughter Cosette, and raises her to adulthood. All the while, he is being hunted by Javert who knows he is the escaped prisoner. Jean must move frequently and quickly in order to avoid being captured and to keep his commitment to Fantine. Everywhere he goes, he carries one of the silver items he stole from the Priest as a reminder of the good that was done for him.

Ultimately, Jean does die. When he is dying he is assured that he has failed, and his life has been all bad and that he cannot be worthy of any love or forgiveness from either human beings or a supreme deity. He is wrong.

Jean’s rises and falls, stops and starts, and zigzagging journey through life is our own. We are all every day effectively starting anew with a new opportunity to do right. Some days we steal the silver and fail miserably and some days we keep commitments to our friends no matter how hard they may be. Through it all, our worthily unworthy lives are waiting for that validation; waiting for that love. We all want to be embraced, and told “Well done, thou good and faithful servant!” We want to be welcomed by our dear departed as Jean was by Fantine. We want to share in that joy together; a joy that only a life that has known how bitter the fruit has tasted can understand and can truly appreciate the milk and honey of the Gospel. Redemption in its truest fashion is to be received into the presence of God, our divine potential fulfilled and our true home realized once again. No longer the miserable ones, but the exalted ones.

It’s not just a piece of the silver he stole that he carries around with him. It’s the candlesticks that the priest GAVE to him after telling the police that Jean didn’t still the silver. “You forgot, I gave these also…”

Jean carries around, not a reminder of his own sins, but a reminder of the love and goodness that there is in the world.

In my haste to paraphrase I neglected to mention that it was indeed the candlesticks that were offered to him.

I did not indicate he carried the items to remind him of his sins though, I indicated that it was “as a reminder of the good that was done for him.” Which it indeed was.

We saw the musical as a family this summer. I got the impression he’d served his sentance (which was lengthy due to earlier escape attempts) and had been relesed, but that the parole requirements were so onerous, and made it near impossible for him to reintegrate with society, that in order to do so he had to change his identity. Javert was hunting him because he’d broken parole. I do think that’s an important point looking at repentance – forgiveness, and whether or not we allow others and ourselves to move on from past mistakes, and become new people, or whether we hold them back/are held back with constant reminders of those mistakes, as Jean would have been, had he not changed his identity, and become a ‘new’ person quite literally.

You realize, of course, that the actual title of Elder Featherstone’s book is “The Incomparable Christ Our Master and Model,” and that his last name is Featherstone rather than Feathertsone.

However, I find it somehow curiously apt to think of Christ as “Our Master and Mode,” as you have rendered it.

🙂

I’ve edited to fix my typos. It makes me incredibly sad that was your takeaway from this post though.

Edited to add: It makes me sad, because it means that *I* have failed in my purpose in writing this two-part series. Bit of a kick in the gut to realize one has wasted two weeks worth of work.

I could not bear to think of you living under the impression that my only takeaways were those trivial orthographic points to which I called attention, so permit me to clarify:

I felt I could add nothing substantive to what Hedgehog wrote (above), but I did feel I could help you out a bit so that others of a more captious nature would not see the opening lines of your post here and dismiss the whole on account of a few orthographical flubs.

Believe me, as a published write (my runaway success of a book of poetic satires, “The Cosmic Oddball” has done surprisingly well) I am the first to support my fellow writers.

Might I add, too, that your post jibes beautifully well with the ideas put forth in a book I am (serendipitously enough) currently reading, titled, “The Case for Christian Humanism” by Franklin and Shaw, which demonstrates how God became human in order to show us how to truly be human in the fullest and most fullfilling sense.

I shall follow your future output with great interest.

Godspeed

Notice, too, that I myself have just committed a blunder, above, writing “published write,” instead of “published writer.” We can all learn to be better humans! 🙂

I watched this movie with my children and they were immediately struck my the severity of punishment for someone who was only trying to save a family member from hunger.

To me this movie is profound in teaching the difference between the two great commandments and the pharisaical adherence to legalistic interpretations.

While the message is something that escaped the Pharisees and many ecclesiastical leaders today it is also simple enough for a child to grasp.

The contrast between Jean and Javert really drew my attention. Neither are bad people. Javert has a warped moral code, but believes firmly that he is doing God’s own work. In other words, while his entire life’s mission seems to be punish good people with no regard toward the broader consequences in terms of suffering, he doesn’t see it that way and he is acting out of duty rather than malice. Misguided? Considerably so, and there is a lesson in that.

Jean, the criminal, is of course the epitome of virtue, sacrifice, goodness and love. Every time I see the movie I am overcome by his impossible standard if goodness. Jean to me is a type of Christ (who died a criminals death).