by Mike Barker

Ah, yes. Race. We’ve all heard the aphorism, “Two things you never want to discuss are religion and politics.” For many whites, we want to add a third thing, “Don’t talk about issues of race.” But to be honest, we must. Especially those of us born into white privilege. It’s a discussion where us whites need to do a lot more listening to your Black and Latino brothers and sisters and do a lot more talking amongst our white-selves. But it’s hard work. To be honest, it seems most progressive and post-Mormons don’t want to talk about it unless it is to shame the Church. Often the converse is true for traditional believing Mormons – race is only discussed when trying to defend past racist policies and ongoing institutional racism. The white American LDS Church just hasn’t figured out how to talk about race and racism as it is reflected in our individual lives; that is just too painful.

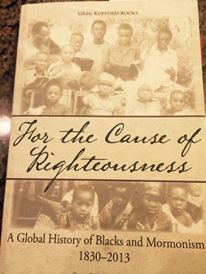

With that being said, Russell Stevenson’s opening preface to, For the Cause of Righteousness, is a self-examination of his own white privilege. In his opening paragraph he states:

“One of the tragic luxuries of living a white narrative is the ability to entertain the delusion that non-white populations and their struggles are, at best, irrelevant.”

Later in his preface, Stevenson sets up the boundaries of how he is going to approach the global history of Blacks and Mormonism when he states:

“Religion is made on the ground as well as it is revealed from Mount Sinai.”

That is, Mormonism’s racial attitudes descended from leadership, but also came up from the grass roots. This is a controversial view for some, as it puts some of the blame on the Mormons that are not in high leadership positions. Or to be even more explicit, some have called Stevenson’s view, “victim blaming.” As Stevenson constructs his approach, he presents a complicated and compelling argument of why/how “leadership” doesn’t always lead.

CHAPTER ONE

In chapter one, Stevenson weaves the well known story of early Mormonism, but does so through the lens of race. By doing so, he makes the well known (and often boring) story new. As he does so, he tells the story through the narrative of three early Black Mormons:

- Elijah Ables

- Jane Manning James

- Black Pete

- He also introduces two Black Mormons that many may not be familiar with: Milla and Cynthia (page 10).

This is not a criticism, but just something to be pointed out. The stories about the five black Mormons mentioned above aren’t able to tell their own stories with their own voices, except for Jane Manning James, because we don’t have any of their writings. Where their voices can be found, Stevenson allowed them to tell their own story with their own voice.

CHAPTER TWO

Chapter two introduced to me some new stories that I had never heard of, nor considered. The most shocking was the connection between Orson Hyde’s 1841 racist concerns that Blacks would “rise above” and his 1845 statement that those who remained undecided between Young’s and Rigdon’s claim to authority, resembled premortal spirits whose wavering assured them birth into black bodies. This is the first time, we have on record, that a connection was made between black skin and Mormon pre-existence.

Stevenson also introduces the names and stories of other early Black Mormons (some controversial and others less-so):

- Q. Walker Lewis

- Joseph T. Ball

- William McCary (McCary was baptized by and married by Orson Hyde to a white woman, Lucy Stanton, daughter of a former Stake President – weird, given Hyde’s deep racism).

It is Lewis’ son’s marriage to a white woman that triggers some of Young’s earliest racist comments (1847). One does have to ask the question, why did McCary’s marriage to a white woman not cause the same vitriolic response by Young? Answer: McCary and Stanton had no children, while Lewis’ son’s marriage did.

Stevenson then begins to weave the narrative of how Young and others, such as John Bernhisel and George A. Smith, begin a complicated and ugly dance between slavery and Utah’s desire to become a territory. Stevenson argues that it’s the Mormon’s need to gain southern support for statehood that took Mormonism deeper and deeper into a racist hole that we are still attempting to get out of today. It is during these debates that we see some of the early and public disagreements between Parley P. Pratt and Young, such as when Pratt, in 1854, “blasted” American society for its, “treatment of Mormons, the Indians and the negroes.”

Stevenson points out that it was shortly after Utah’s embracement of slavery (called bonded service) that we get Young making theological ramifications for the place of Blacks in American society (January 1852). Namely that they were the children of Cain and that they could not have priesthood. As Stevenson points out, in the 1850 census, 26 slaves are identified. This, “enabled the Saints to accept slavery without facing it directly.” By 1860, there would be 200 Black slaves.

Although earlier, Orson Hyde had connected the Black race with premortality, it was Orson Pratt that connected pre-existence with the race-based priesthood ban (1853). This, however, doesn’t seem to be a settled issue. In 1870, John S. Lindsay (a Godbeite) argues against the “fence-sitting” theology in the Salt Lake Tribune. Despite some dissinting voices Stevenson rightly states:

“What had once been an opportunistic response to win the support of the southern states and even the Winter Quarters Saints had metastasized into a hard-boiled racial prejudice.”

When discussing the doctrine of the priesthood/temple ban, Stevenson avoids the easy pitfall of presentism. That is, he does not call this ban a “policy” but rather a “doctrine” — something almost completely lost to modern LDS apologists. While succinctly labeling this as a doctrine, Russell also points out its fluidity. Was the priesthood and temple ban do to premortal unworthiness or due to ancestry? Then we throw the Book of Abraham into the mix. Linking the Book of Abraham text to the priesthood/temple ban did not occur until 1907 via a private letter from Joseph Fielding Smith to Alfred Nelson. I remember (embarrassed as I am to admit this) as a teenager, living in California’s Central Valley, wondering how all of this worked out.

After laying out some of the chronology and fluidity of this doctrine, Stevenson then frames Mormonism’s racism as an attempt to prove their “Whiteness” to America. His arguments reminded me of Terryl Givens’ book, Viper on the Hearth. That is, much of the anti-Mormon polemics was in framing Mormons as anything other than white: Asiatic, Oriental, Indian thuggess, Chinese immigrants, Turks, Hottentots, polygamist Blacks. There was even a popular song at the turn of the century called, “The Mormon Coon.” It was Mormonism’s attempt to not appear as “the other”, but rather white, that further bogged Mormonism into a racist pit. And less we forget, this racism affected real people. Jane Manning James was never allowed to take out her own temple endowments.

As Russell states: “the Saints attempted to compromise with the white American establishment by adopting the racial values they celebrated.” And their attempt didn’ t go unnoticed. President Theodore Roosevelt “celebrated the Mormon’s ability to build of the Anglo-Saxon population through their high birthrates, since he feared that whites would lose their preeminence in the modern world.” Roosevelt, commenting on Joseph F. Smith’s forty-two children exclaimed, “That’s Bully! No Race suicide there!” Geez.

Chapter 3

Chapter three traces how Mormonism went from being seen as “the other” to fully embracing a very racist doctrine as it pertained to black women and men.

It starts with the story of Elijah Ables ordination and the later questions of whether or not his ordination actually happened. It then moved onto the less well known story of physician, David L. McDonald encouraging the discontinuance of using a communal sacrament cup. Why? Possible spread of disease from black Mormons. Stevenson then touches on the KKK in Utah and moves onto discuss the black Mormons that stayed in Utah after WW II in an effort to correct “the racial insjustice that had existed in Utah Mormonism for the past generations.”

In 1865 Brigham Young closed the South African mission and in 1913 it was reopened by George Albert Smith’s half-brother, Nicholas Groesbeck Smith. The story of Goresbeck Smith was enjoyable. I asked myself why that was? My best answer was that his story eased my guilt over how blacks have been treated by the largely white LDS church. He pushed to allow black Africans to receive their temple ordinances. He also formed a strong relationship with a black man, William P. Daniels. Daniels received a blessing from Joseph F. Smith, then President of the LDS Church, that he would one day receive the priesthood. Daniels would later form an ad hoc congregation and began a study group in January 1921. Sometime between 1929 and 1932 Daniels was “set apart in what was an unprecedented calling in Mormon history: the first black branch president never ordained to the priesthood.”

After the story of Nicholas Groesbeck Smith and William P. Daniels, we learn of the 1948 First Presidency direction that “no man was to be ordained to or advanced in the priesthood until he had traced his genealogy out of Africa.” This eventually led to full-time missionaries being appointed to work as geneological researchers in hopes of “increasing the Priesthood holders among the male members of the Church.” In a conversation I had a few years ago with my father in law, he recalled the burden the missionaries had in places like Brazil to make sure that converts didn’t have any black African blood before being ordained to the priesthood. He told me what a ridiculous idea it was and that from his view point back then, it was something that simply wasn’t sustainable.

In 1954 David O. McKay visited the South African saints in large part to address the white saints’ concerns that they did not have pure European blood. McKay reiterated the longstanding pre-mortal rhetoric. Eventually the Church would appropriate “South African nationalism [as a] manifestation of Mormons’ hardwired survival instincts coupled with generations of racialized discourse – discourse that itself had been adopted as the Saints struggled to survive the racial currents of American society.”

The ban on black Mormons was not only something that came from the LDS Church, but also came from the South African government. This is told through the story of Moses Mahlangu who in the mid-1960s learned of the Book of Mormon and wished to be baptized. Mission President Howard Badger “applied to the government of Pretoria and received permission to baptize blacks.” But in a horrible twist of events, Badger was then prohibited by the LDS Church to baptized Mahlangu because, “the gospel was to be preached to the withes and then to the blacks.” Mahlangu continued to listen to LDS services through a window until his baptism in 1980.

Stevenson then turns his attention away from South Africa and over to Brazil. The missionaries initially only preached to the Germans living in Brazil and avoided dark skinned people. Mormon Senator, William King, openly criticized the Nazi regime on the U.S. Senate floor while at the same time Brazil mission president, Rulon Howells recommended racially segregated units. This was met by protest from the black Brazilian members. Howells then implemented a strict lineage-screening team to ensure that baptized members were free from “the blood.” This of course had obvious problems such as when the Ipiranga branch president discovered he had what he believed to be an African ancestor. “The mission president released him from all priesthood duties. Seven years later the First Presidency nullified the decision and reinstated his priesthood.”

Stevenson then explores the work of LDS sociologist Lowry Nelson. It was intriguing to see what an open secret the temple/priesthood ban was to white members of the Church such as Dr. Nelson. Nelson would eventually go toe-to-toe with the First Presidency regarding the ban. It was during this time that the Church issued its most rigid statement regarding the ban. It connected the ban to pre-mortal life but would receive limited circulation.

Chapter 4

From Brazil Stevenson moves the story to West Africa. He does so by weaving the stories of Dr. Virginia Cutler, the Church’s leading representative for international development, the Nigerian petition for LDS missionaries, LaMar Williams, and the First Presidency’s ongoing struggle to determine what to do with black Africans. It was during this time that a Nigerian Cal Polytch student, Ambrose Chukwu, learned of the Church’s racist doctrine. He would write an angry article for the Biafran newspaper, Nigerian Outlook. This led to the Nigerian government issuing blocks on four missionary couples seeking to enter the country. LDS educator, Lowell Bennion learned of the article and “blushed in shame and anger to read it.” “[We] have sown the world wind and are reaping the world wind.” Black Nigerians would later ask, could not

“some good, clean Negro person be given the priesthood so that our work may go forward?”

One of the most intriguing Nigerians, Moses Okoro, would urge the Saints to endure. Why is he so intriguing? He was a polygamist believer. I would have loved to learn more about him.

One of the most dynamic, faithful, and controversial Saints was Ghana’s Rebecca Ghartney Mould. She founded some of Ghana’s first Mormon congregations. She would preach distinctively Mormon doctrine while blending it with Pentecostal Christianity and native ritual. She was called “the Prophetess” by the Ghanian men and women of her congregation.

A white Mormon that helped begin the shift in Mormonism’s opinion of blacks was LDS explorer, John Goddard. He would document his expedition on camera and then turn them into documentary films such as Kayak Down the Nile and Bongos down the Congo. This is not to say that Goddard did not hold to some racist views of Western superiority himself. He did, but his trips forced him to question his childhood assumptions. He would later implore Utahns to, “Get to know peoples of the world,” and he would be thanked for showing his “love for God’s many children..[a love that] can’t help but open many doors and avenues unto you to further your understanding of the world and the Lord’s ecumenical enterprise of winning souls to his eternal verities.”

The work that white Mormons did, such as Goddard, Williams, and Cutler, was important. They created a space for black Africans. By creating that space, it enabled Mormons to grapple with their past stereotypes.

We also are introduced to Sonia Johnson, but not within the context of the ERA, rather within the context of race. Stevenson includes excerpts from personal letters of hers and they give us a peek into the struggle some white Mormons had with the temple and priesthood ban. After spending time in Africa, she began to experience a shift in her thoughts regarding race. In one letter she stated that the ban, “just doesn’t make sense to me,” and that she hoped that, “the next President of the Church [after McKay] will receive some revelation about it.”

In his discussion of black Africans, Stevenson avoids the problem that many Mormons find themselves falling into. That is, making the African-Mormon experience the same as the African American-Mormon experience. How often have you heard white Mormons point to black Africa and Mormonism’s growth there to “prove” that Mormonism no longer struggles with racism? Stevenson closes chapter four with the following:

“Africans, unlike African Americans, enjoyed a sovereignty over their own land and culture that African Americans were only now beginning to rediscover.”

CHAPTER 5

Chapter five tackles civil rights in the U.S. One of the interesting figures in this chapter was James E. Faust who at the time was a stake president and the president of the Utah State Bar Association. He would later become an LDS apostle and serve in the Church’s presiding First Presidency. Faust would serve on President John F. Kennedy’s Lawyers Committee for Civil Rights under Law. The committee “worked to defend African American clients too poor to afford legal and courtroom costs.”

One of the more outspoken white Mormons on the issues of race was Dr. Sterling McMurrin, professor of philopshy and John F. Kennedy’s U.S. Commissioner of Education. McMurrin would blast the LDS leadership for its “morally reprehensible negro doctrine.” Other scholars, such as Dr. John Sorenson, BYU anthropology professor, would privately argue with McMurrin that,

“So few realize the degrees which leaders must in turn be followers of the masses…General Authorities have been burned too badly in their efforts at leadership in the past four generations that they are now very hesitant to speak out, perhaps for fear that the members will not follow them.”

McMurrin would affirm Sorenson’s general assessment but asserted that Mormons, “as a whole are very often ready for more forward-looking leadership than they receive.” Stevenson points out that McMurrin was only half right. For the larger body of Utah Mormons resisted federal civil rights legislation. Much of this fear was based around the concern that civil rights would lead to interracial marriage.

Another person that Stevenson introduced me to was Adam Duncan, chairman of Utah’s Advisory Committee to the Kennedy Administration’s Civil Rights Commission. He had learned from his LDS mission in South Africa that the priesthood and temple ban were a “vicious folly.” He would advise the ACLU leadership:

“You don’t slap a Mormon in the face..You try to talk him out of what he wants in a reasonable way. You don’t try to bully him.”

His advice seemed to work. The NAACP president, Albert Fritz, called upon, all affiliated parties, “not to picket any of the LDS churches or missions.”

One thing I had never considered was the possibility, after the 1964 Civil Rights Bill passed through Congress, that the LDS Church could lose its tax-exempt status. Stevenson writes:

“In 1970, Bob Jones University lost its tax-exempt status for refusing to admit African Americans, making it probable that the LDS Church would experience similar scrutiny…The Church’s sponsorship of the Boy Scouts of America came under fire for reserving the ‘senior patrol leader’ position for the young man in each ward who was serving as the deacons’ quorum president [who could not be black].”

CHAPTER 6

We then learn of the Genesis Group. After a meeting in 1971 with three black Latter-day Saints – Darius Gray, Eugen Orr, and Ruffin Bridgeforth – Apostles Gordon B. Hinkley, Boyd K. Packer, and Thomas S. Monson received First Presidency permission to form an official LDS Church auxiliary in hopes of retaining black LDS members and establishing a new “beginning” in Mormon race relations. Genesis Group president, Ruffin Bridgeforth, acknowledgd the difficulty the Genesis leaders faced:

“We did feel that there would be many problems. We had dissension, and we had people who were dissatisfied…Trying to keep them calm was a constant challenge.”

The LDS Church continued to face outside pressures. To streamline media inquires, President Harold B. Lee formed the Public Communications Division (PCD). One of the shocking things I learned about the PCD was its popular television ad series Homefront. It was the Church’s attempt to “reorient the conversation” away from the Church’s racist doctrine. The ads were “one-topic lessons apiece: the value of honesty, the importance of marriage, spending time with children, the centrality of family to Mormon teachings.” Stevenson continues, “Strategically, these well-written and well-acted spots refurbished the Mormon message in a way that took the attention off the grinding conversations about race.” The series would go on to win three Emmys, eighteen Clios, and an honorary award from the National Parents Day Foundation.

I was born in 1973. I remember these ads. My favorite, by far, was the one where a boy broke the window of some grumpy old man. One of the reasons that it was so cool was that it was rumored in my East San Jose neighborhood that the black boy was the same actor who appeared in the 1980’s Pepsi T.V. ad with Michael Jackson.

Yes. I found Michael Jackson’s Pepsi Generation commercials. Remember the scandal when his hair caught on fire? Anyways, the second clip has a boy dressed in Michael’s red Thriller jacket and his white sparkly glove. That’s the black boy that all my friends were convinced was the same boy in the Mormon commercial. He was the coolest kid when I was around nine. And it almost made it cool to be Mormon.

And I totally remember these commercials too. Especially the one where the dad yells at his boy for letting the front door slam:

What shocked me was that these popular commercials, which made me appear less weird to my white and black friends, were all to wag the dog with regards to our racist doctrine. The commercials were powerful. Really. We’v all had a conversation with a non-LDS friend that has mentioned how family-centered Mormons are. Much of that perception has come from these commercials. Now, our racisms has reached back and tainted a very lovely memory of mine.

Stevenson put it perfectly:

“The advertisements drew an embedded message out of its deeper context and refashioned it as one of Mormonism’s defining and public characteristics, an image all the more painful for black families longing for their temple blessings.”

What has always intrigued me were the stories of black Americans that joined the LDS Church prior to 1973. Why would one do this? How informed were they of the Church’s racist doctrine? One of these converts was Wynetta Martin, who would become the first black member of the Mormon Tabernacle Choir. She moved from Christianity to atheism to Mormonism. After joining the Church in 1966, she moved to Utah to attend BYU. In 1970 she was hired as a “research consultant on black culture,” for BYU’s nursing program “because so many of the girls” had “never talked with anyone of the black race.” She also became a popular speaker for Mormon audiences.

Martin would tell stories of her interactions at her speaking engagements. One woman asked Martin if she was from the West Indies. Martin responded that she was in fact a “Negro.” Martin recalls that the woman “was close to collapse.” She then wrote that the woman was not “vicious” but “naive.” Her interactions with white Mormons “revealed their uncertainty in carrying out interracial dialogue, and she shared them, both for their comedic quality and also as subtle instruction for dealing with mixed-race gatherings.” Stevenson writes:

“The Mormon people loved her story but there was a problem. She was not “allowed to speak for herself,” Stevenson surmises. John D. Hawkes, publisher of Martin’s autobiography, was concerned that her story would be interpreted as activism. So, he attached an essay to her autobiography entitled: Why Can’t the Negro Hold the Priesthood. “

Yeah. I know.

And there are the stories of more radical Mormons like Douglas Wallace and Larry Lester. In 1976 Wallace, a Portland attorney, ordained Lester, a black man, to the priesthood. This led to Wallace’s excommunication and his law suit against the LDS Church.

Also important to the story is Dr. Lester Bush. In 1973 Dialogue published the physician’s article entitled, Mormonism’s Negro Doctrine: An Historical Overview. It was reported by President Kimball’s son and biographer, Edward, that this article played a significant role in President Kimball’s 1978 revelation. On a personal note, Bush’s article also played a significant role in my understanding of the temple and priesthood ban.

Stevenson then takes us back to Brazil. I served a Spanish-speaking mission. In the second discussion, those of us who taught in Spanish, had an extra part that our English-speaking counterparts didn’t have. We had to talk about infant baptism.

I learned that similarly, those missionaries serving in Brazil had to teach a special “seventh discussion” on – you guessed it – why black men couldn’t have the priesthood. The approach was first couch the discussion with some weird rhetoric that there were some “marvelous teachings” reserved only for black members. Barf.

We then are shifted from Brazil back to Ghana. We learn of the Ghanian’s persistence in being officially recognized by the LDS Church. The Prophetess, Rebecca Mould, prophesied “that the Lord had poured out unto us the blessings that we had sought for many years.” She also promised that the, “Lord has granted us the glory and honor we deserve and has granted us the opportunities to become like angels.”

Then the 1978 revlation came

Stevenson then reviews the recollections of several of the apostles that were present when President Kimball presented to the Quorum of the Twelve Apostles the topic of the temple and priesthood ban. The meeting was on June 1, 1978. Two apostles were absent: Mark E. Peterson was in Brazil headed for Quito, Ecuador and Delbert L. Stapley was ill in the hospital. Some have speculated that President Kimball purposefully waited for Elder Peterson to be out of the country to bring the topic to the table. It was not until June 8, 1978 that President Kimball called Elder Peterson to inform Peterson of the Quorum’s decision to extend all the temple and priesthood blessings to all members, regardless of race. Peterson expressed support. The First Presidency then visited Elder Stapley in the hospital. He also supported the decision.

On June 10 the public was told of the revelation. On September 30, 1978 the Church, by common consent, voted to uphold the revelation and it was later canonized in LDS scripture. Many rejoiced. But not all. One of my brothers in law pointed out to me how “amazing it is to hear how many Mormons didn’t like the racist doctrine and how many were elated with the revelation.” He then sarcastically pointed out, “There are no members today that would say they upheld the racist doctrine and were upset when it changed.” Yes. It’s amazing how time changes our perceptions.

But not all were happy with the revelation. About a month later a group calling itself “Concerned Latter-day Saints,” paid for a full-page advertisement in the Salt Lake Tribune questioning the wisdom of the new revelation.

CHAPTER 7

One of the ramifications of the revelation was that the Church officially recognized the Saints in Nigeria and Ghana. With this recognition came the question of what to do with the already standing branches. Also with the recognition, came the Americanization of West African churches. With this came the replacement of the Ghanian prophetess, Rebecca Mould, with Charles Ansah. Eventually these changes proved too much for Mould.

Ghana was not the only country that proved to have difficulty with Mormon-black reconciliation. South Africa also presented its unique problems in the form of a pro-apartheid government. After a 1981 national election in which little hope was shown that things would change, the LDS Church defied racial violence that was wracking the area by announcing that temple ceremonies would be racially integrated.

But things were not always smooth for the LDS Church members. Integration did have push-back. Some Saints stopped attending church after the all-white meetings ceased. Black LDS saint, Vivean Clark, recalls that during a Relief Society dinner, a priesthood leader drew a hammer and sickle on her name tag. Some white members expressed that they would not know what to do if a black African came to the veil of the temple.

One of the critiques I have of Mormon history, when it comes to blacks, is that it often hyper-focuses on American racism and how it affected the American Church. The New Mormon History must broaden its perspective and must not always be about the white missionaries. Stevenson has effectively avoided both of these criticisms.

Stevenson then weaves into his narrative some prominent and important black Mormons:

- Joseph Freeman – first black man to be ordained after the ban was lifted; it occurred within hours of the change

- Eldridge Cleaver – Black Panther

- Paul Devine – Mr. Universe

- Mary Sturlaugson – First black woman missionary

- Samuel Bainson (a convert of the Prophetess Mould) served as the first African missionary

- Only thing missing is first black woman to receive her endowments

On page 184, Stevenson addresses something that has bothered me for a while. When the Church has published articles about black members, it often focuses on the growth in black Africa and rarely deals with the black American Mormon experience. This give the sense that “all is well in Zion.” But the experience of black Africans is different than those of black Americans. This is reflected in the statistics that Stevenson provides:

- Between 1975 and 1980, the black Mormon community grew by 42%; only 19% of that growth came from African Americans.

- By 1987, black Mormons in South Africa outnumbered Africaaners by a ratio of more than 20 to 1.

Stevenson then touches on a rumor I’ve seen floating around the Mormon internet and podcasts regarding a possible repudiation of the temple and priesthood ban. Stevenson writes:

“In the summer of 1997, a group of Mormon intellectuals, professionals, and Church leaders gathered in Los Angeles to develop a plan for the Church to disown its 150 years of racism, including a call to cease publication of Bruce R. McConkie’s Mormon Doctrine….”

You’ll have to grab the book to read how the story ends. It’s on page 186, under the subtitle, Truth.

Under the same subtitle, Stevenson discusses the issue of baptizing black West African polygamists. It’s weird to see such a concern, given that blacks could’t have the priesthood nor attend the temple when this question was raised. The Church’s repudiation of polygamy was Church wide while the temple and priesthood bans were limited to blacks. To add another layer of weirdness, polygamy never affected blacks while it was being openly practiced. I imagine that a similar question would not have been asked if it were white polygamists. Again, you’ll have to grab the book to see how the issue was resolved.

PART II: THE DOCUMENTS

This part of the book was a sweet surprise. It has six chapters (8-13) each containing long excerpts from primary documents with introductions that contain the historical context in which each of the documents were written. Each chapter is divided chronologically:

- Chapter 8 Making Race in Mormonism, 1833-47

- Chapter 9 Origins of the Priesthood Ban, 1847-1849

- Chapter 10 White Zion, 1852-1903

- Chapter 11 A Sleep and a Forgetting: Losing the Black Mormon Heritage, 1902-49

- Chapter 12 American Mormons Struggle with Civil Rights, 1953-69

- Chapter13 Reconciliation, then Truth, 1971-2013

Here are some of the highlights of Part II:

- September 1832 – Elijah Ables is baptized

- July 1833 – Church Publishes a very progressive view regarding blacks and then redacts it

- March 1836 – Elijah Ables is given priesthood

- 1810-93 – Jane Manning James

- 1845 – Elder Joseph T. Ball, a Boston African American priesthood holder

- May 1847 – Earliest mention of a possible priesthood ban

- Summer of 1847 – William Smith blasts Orson Hyde for baptizing a black man, William McCary, yet W. Smith had baptized black Mormon, Walker Lewis

- February 1849 – Brigham Young articulates for his first time that blackness = cursed

- January 1852 – Apostle Orson Pratt and President Brigham Young go back and forth publicly regarding slavery. Pratt denounces Young’s pro-slavery speech

- February 1852 – First time that Young publicly correlates blackness with curse with priesthood ban

- June 1913 – Booker T. Washington visits Utah

- September 1967 – Ezra Taft Benson attacks Civil Rights Movement

- July 1978 – Fundamentalists attack change in doctrine

- December 2013 – Church repudiates past racist teachings

CONCLUSION

I found this book to be highly valuable and worthy of it being the Mormon Historical Association’s Book of the Year. Its premise seemed too much for one book to contain: discuss the global history of blacks and Mormonism. Yet, Stevenson is able to do so responsibly, accurately, and with good documentation.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks