I admittedly took my sweet time to sit down and watch Ex Machina. I had heard mixed reviews, but I was interested in the science fiction aspect of the story. In one of the film’s more memorable scenes, the character Ava asks Caleb: “Are you a good person?”

Caleb pauses for a moment, seemingly in shock that such a question would be asked. As time goes on, Caleb’s personality and intent continues to unfold before our eyes. His behavior, a stark contrast to the seemingly singular antagonist Nathan.

By the end of Ex Machina, I was left feeling rather unsettled. The series of events that led to the demise of Nathan and grim fate that most likely awaited Caleb felt like an injustice had occurred in the film universe.

“This couldn’t possibly happen to a good person, the supposed hero of the story,” I thought.

I felt a sort of attachment to Caleb, as I imagine many did (based off of the various ‘what the bleep just happened’ posts online). In film, literature, culture and religion, we often attach ourselves to the benevolent characters in any given narrative. Even the anti-hero, whose deeds generally counter traditional standards of benevolence, has a level of goodness some can identify with (in the messiness that can be a part of our own being.) In Ex Machina, Caleb’s supposed status throughout the film is one that stems from goodness and we want to root for that. By the end, we realize, perhaps he wasn’t so good after all. For me, that was one of the more chilling aspects of the film. Maybe, in the image we project, we are not as good as we think we are.

Before I watched the film, the question of “goodness” manifested itself in various ways in my Christian Ethics course last semester. What does it mean to be a good person? What virtues are required to attain a certain level of goodness? I, like Caleb, had to take a step back to reflect; more so on those things in my life and my relationships with other people and the work I hope to do in my own ministry. How do justice, courage, temperance, prudence; supplemented by the theological virtues of faith, hope and love, operate in my life? The example of goodness for the Christian theist is of course more often than not Jesus the Christ. Being Christ-like seems to be the 11th commandment in our duty to our fellow human beings. Within this, we find a theology of goodness, a reflection of care for the Creation as God cares for us. As a living theology, it counteracts others based in death and destruction. On the surface, one who engages with this theology can believe they are good on the principle of following Christ alone. At the same time, in trying to project the image of being good, we can find ourselves forgetting to do good. It is the difference between, as David Brooks describes in his work The Road to Character, Adam I and Adam II; a split between the internal and external values, respectively, that define our character. For me, social justice activism, and the theology that can accompany it, are not immune to the question of character.

Are our theologies based in the care of the Creation or are they destructive? Do we rely on forgiveness in the form of cheap grace? Is our kindness marred by personal gain?

These of course, are questions one can only answer for themselves.

Throughout Ex Machina, the audience is led to believe that Caleb is a good person. In a more thorough examination of the film, one finds that it is more likely that Caleb and Nathan are two points at the opposite ends of a destructive spectrum, making the question of “are you a good person” and his response even more disturbing. In a theology of goodness, there is value in pausing and reflecting on those actions versus projections. Our being is full of messiness and contradictions by which, as a professor of mine once explained, can be confronted through transparency. But once the question is raised, will we be able to sit with the answer?

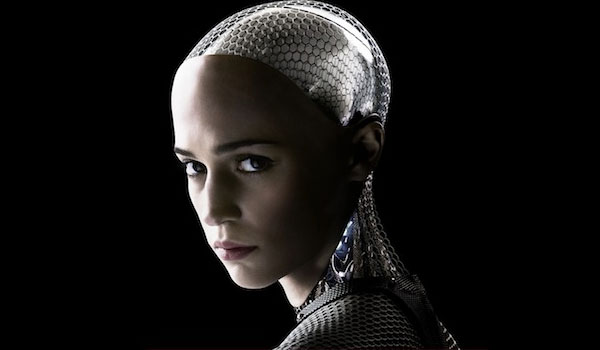

[1] Image from Ex Machina, retrieved from Google

Wow. I never looked at the movie through that lens.

When I saw it (in the theater, so it’s been a while), during the scene where he’s watching Ava put on her full skin, I remember thinking “we shouldn’t be seeing this.” It was her moment, and he shouldn’t have been watching- and our identification with Caleb made us peeping toms with him. My initial reading of the film was more along the lines of destructive masculinity, where Nathan and Caleb are two different kinds of man, but neither sees Ava as fully a person (and while Nathan’s masculinity is more monstrous and doesn’t try to justify itself with goodness, Caleb really believes that he is seeing her as a person). As the film finished, I realized that if the movie had been from Ava’s perspective, Caleb would have seemed kind of creepy from the beginning, but by sticking us with Caleb throughout, we have to realize it on our own.

I watched this film so recently, and am grateful for your thoughtful perspective. Thank you!