Several weeks ago, I read an essay by Margaret Toscano entitled “Is there a place for Heavenly Mother in Mormon theology?” [fn 1] After an insightful analysis of the institutions surrounding Mormon theology, she answers, “No.” To critique her conclusion, I recruited a Deseret Book novel by highly conservative white upper-class male Mormon author Chris Stewart, R-UT, wherein Heavenly Mother appears – albeit as silent, deeply respected, uniquely compassionate and concerned with her children’s wellbeing, and without institutional prestige [fn 2]. In this light, I suggested we reformulate Toscano’s question: “What is the place of Heavenly Mother in Mormon theology?” If Stewart’s book is any valid indication, She is the exemplar and mirror of the position of women in general in official LDS discourse and institutions. As ideal human women are described, even so She is; likewise, human women are to model their persons after Her. Instead of lamenting Heavenly Mother’s supposed lack of place, it would be better that we critique this image of her, with which many women cannot relate (though many others can). We are really asking if each individual woman has a place in Mormon theology.

Several weeks ago, I read an essay by Margaret Toscano entitled “Is there a place for Heavenly Mother in Mormon theology?” [fn 1] After an insightful analysis of the institutions surrounding Mormon theology, she answers, “No.” To critique her conclusion, I recruited a Deseret Book novel by highly conservative white upper-class male Mormon author Chris Stewart, R-UT, wherein Heavenly Mother appears – albeit as silent, deeply respected, uniquely compassionate and concerned with her children’s wellbeing, and without institutional prestige [fn 2]. In this light, I suggested we reformulate Toscano’s question: “What is the place of Heavenly Mother in Mormon theology?” If Stewart’s book is any valid indication, She is the exemplar and mirror of the position of women in general in official LDS discourse and institutions. As ideal human women are described, even so She is; likewise, human women are to model their persons after Her. Instead of lamenting Heavenly Mother’s supposed lack of place, it would be better that we critique this image of her, with which many women cannot relate (though many others can). We are really asking if each individual woman has a place in Mormon theology.

I think this question makes at least the presumption that the Deities we worship, our Heavenly Parents, are meant to model individually for individual humans how to lead individual lives in a gendered fashion: Heavenly Father as exemplar male, Heavenly Mother as exemplar female. In our Parents we see who we can and should become. All humans can and should conform to a single image in which they were made, the image of God or Goddess.

The assumption of God-as-model/mirror has, in other faith traditions, given rise to the richness of identity theologies, all of which ask the question: “What if God were like me?” While these theologies often provide beautiful meditations on the place of each human in the universe, I think Mormon theology holds several proposition that render them invalid save as thought experiments (albeit important ones). First, Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother are embodied beings with particular histories. Second, as embodied beings with particular histories ourselves and the ability to become Gods comparable to our Parents, nevertheless do we expect that even following our conformation (through Christ’s atonement) to principles of divine worthiness, we have personal differences that existed before our time on Earth and will persist hereafter [fn 3]. Just as affirming that all humans are gods in embryo, as Mormons do, does not explicate differences among humans, even so recognizing that Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother are fully realized Gods does not negate their potential eccentricities. If divinization and personal diversity are not mutually exclusive, we must confront the conclusion that, in expecting our Heavenly Father and Mother to be “all things for all people” or by metaphorizing them, we are very likely doing violence to their identities as unique individuals. By seeking a self-reflection in Their faces, we question Their existence as Others-than-us and absolve ourselves of the responsibility to love something to which we might not fully relate.

“What if God were like me?” While these theologies often provide beautiful meditations on the place of each human in the universe, I think Mormon theology holds several proposition that render them invalid save as thought experiments (albeit important ones). First, Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother are embodied beings with particular histories. Second, as embodied beings with particular histories ourselves and the ability to become Gods comparable to our Parents, nevertheless do we expect that even following our conformation (through Christ’s atonement) to principles of divine worthiness, we have personal differences that existed before our time on Earth and will persist hereafter [fn 3]. Just as affirming that all humans are gods in embryo, as Mormons do, does not explicate differences among humans, even so recognizing that Heavenly Father and Heavenly Mother are fully realized Gods does not negate their potential eccentricities. If divinization and personal diversity are not mutually exclusive, we must confront the conclusion that, in expecting our Heavenly Father and Mother to be “all things for all people” or by metaphorizing them, we are very likely doing violence to their identities as unique individuals. By seeking a self-reflection in Their faces, we question Their existence as Others-than-us and absolve ourselves of the responsibility to love something to which we might not fully relate.

We can thus see that our Heavenly Family might be more analogous to our earthly families than we may have ever thought. Interestingly, Mormons have for a long time recognized that acknowledging heavenly siblinghood implies no similarity between those siblings; while other Christians perplexedly balk at our assertion that Jesus and Satan are brothers, we point them to Cain and Abel. For examples of righteous difference, we can look to Nephi and Sam, Moses and Aaron, Ammon and Aaron.

We can thus see that our Heavenly Family might be more analogous to our earthly families than we may have ever thought. Interestingly, Mormons have for a long time recognized that acknowledging heavenly siblinghood implies no similarity between those siblings; while other Christians perplexedly balk at our assertion that Jesus and Satan are brothers, we point them to Cain and Abel. For examples of righteous difference, we can look to Nephi and Sam, Moses and Aaron, Ammon and Aaron.

This brings me to another Mormon proposition: that no one can attain godhood alone, but only as members of celestially successful couples. (Indeed, the requirement that humans be married in order to become gods is the very basis of a belief in Heavenly Mother!) Thus, perhaps we should not take the individual members of the Heavenly Couple as our models for men and women, but instead see the Heavenly Couple as a unit as a model for each earthly couple as a unit. It is the couple that is divine and godly; individuals are to an degree insufficient for exaltation. With this in mind, we should observe that even among heterosexual couples, there are a broad range of adaptations that help families to function within celestial guidelines. There is no single guide to marriage that can micromanage a family; everyone has to devise a system that works, wherein “fathers and mothers … help one another as equal partners” [fn 4]. Just as our sisters and brothers on Earth find different paths to celestial familyhood, our Heavenly Aunts and Uncles might have differing styles of Celestial Parenting.

All this is to say that perhaps the situation we experience on Earth, with a silent, implied Mother in Heaven, is not universal. It could simply be a matter of our particular embodied experience with particular Embodied Parents, just as each of us has his or her own set of earthly parents with their personal quirks and modes of living. Perhaps we see in this a matter of divine progression: having parented on an earth and been perfected in that sphere, the next step is to Parent from Heaven, learning along the way and adapting as needed. Moreover, perhaps the place of identity theologies is not so much to give us insight into our Father and Mother in Heaven, but rather into humans’ places and experiences as to-be Gods. If we are to believe in embodied Gods, we must change the way we conceive of divine modeling.

[1] Margaret Toscano, “Is there a Place for Heavenly Mother in Mormon Theology?,” in Discourses in Mormon Theology: Philosophical and Theological Possibilities, ed. James McLachlan and Loyd Ericson (Salt Lake Citys: Greg Kofford Books, 2007).

[2] Chris Stewart, The Brothers (Salt Lake City: Deseret Book, 2003).

[3] I realize that there are some Mormon that do not agree with this perspective of divinity and human divinization. However, I believe that it has roots in Mormon history, thought, and folk culture that make it a broadly accepted image; further, it is one that I hold dear, so I will use it.

[4] The Family: A Proclamation to the World.

____________________________________________

Need More Mother in Heaven?

Click here to read the ground breaking article he co-authored in BYU Studies entitled “A Mother There”

A Survey of Historical Teachings about Mother in Heaven”

Click here to listen to the Mormon Matters episode about the above article.

This just blew my mind:

I had never considered this before. We always put Father up as the being to be emulated, but I’d never considered that without Mother, He is incomplete. We should be emulating the Couple.

Wow.

You’re totally right, of course. But… wow. I’ve never heard that said so plainly before. Thank you!

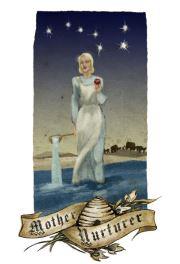

Where did the artwork for this post come from? I notice that the “Mother-Teacher” image has a Wiccan symbol in the background.

The artwork came from an issue of Sunstone, and I recommended them not because I endorse the issue (I have not read it) but because I enjoy the depictions of various roles Heavenly Mother could serve, as well as different physical appearances. The images can be found here: http://www.cafepress.com/shopsunstone/8708466.

It’s very interesting that you note the symbol used there. I didn’t know it was such, but the fact it was used doesn’t really surprise me; apparently, it signifies “the Goddess” in Wicca. Given that Wicca was originally known as “feminist spirituality” (a very presumptuous name, in my opinion), it probably represents the artist’s effort to incorporate a bit of the history of feminism and religion into the images.

Beyond that, though, it’s not an unusual symbol to use. Each of the images incorporates a different astronomical figure to emphasize, I’d suppose, the connection of Heavenly Mother with the cosmos, much as temple visitor’s centers have murals of space behind the Christus. Beyond that, the moon has often been connected with femininity due to its cycle of monthly changes.

Wonderful piece of writing, Michael. Thank you. I absoulutely love the LDS perspective of God and godhood. It’s one of the few places a woman can find a true image, albeit it hazy, of divine feminine. And your union of the father and mother as the formula for godhood is perfect. . . beyond that, and pertinent to some of the conversations going on around here: The power of God (priesthood) comes, not from half of this union, but from the combined union. Food for thought.

Also, the beautiful art is from a special issue of Sunstone Magazine. I actually own a print of the Mother-Teacher image. It’s more lovely in person. (Someone should probably credit the artist here too. Although I can’t remember her name.)

https://www.sunstonemagazine.com/guest-editors-foreword-the-power-of-the-goddess/

It looks like this might be the blog of one of the artists: http://galendara.blogspot.com/2012/04/bad-ass-women.html

I’m confused by the post. At first you sound like you’re going to try to critique the common image of HM as a silent and institutionally marginal divine symbol in Mormonism, but then you seem to end up merely justifying the status quo by suggesting that her silent and implied existence is a consequence of her own (eternal?) individualized idiosyncrasies?

I agree with you that there are problems with our conceptions of deity that make it difficult for them to effectively function as models for ever individual Mormon in all his/her particularities. But the notion that Mormonism’s divine symbols should not serve as exemplary models for out total gendered, individual, familial, and communal identities and experience is about as unMormon as you can get.

Furthermore, I think the suggestion that Heavenly Mother’s absence, silence, or marginalized existence is a product of her own personal quirks is unconvincing, reflects a lack of awareness of the larger (patriarchal) cultural context within which Mormonism took shape, and hardly approaches anything like a critique of Margaret Toscano’s much more persuasive analysis.

I don’t offer conclusions in this post besides that Mormons should be wary of seeing Heavenly Father as the model man and Heavenly Mother (as she is understood) as the model woman. I don’t seek to support the status quo. But I’m also wary of ascribing too much to HF and HM, and think we should critically consider our language and characterization of eternal gender.

Further, I am anything but unaware of the highly patriarchal culture in which these images of Heavenly Mother have taken shape. This article is not meant as a critique of Margaret Toscano save to question her conclusions that 1) there is absolutely no place for Heavenly Mother in Mormon theology at present (which I see as false) and 2) Heavenly Mother must be representative of divine womanhood and a model for all women.

Can we truly use HF and HM as gendered models, though? If we strive for exaltation, we must realize that individual gendered models will not get us there; it will be as bigendered couples that we arrive.

I’m confused by your assertion that “the notion that Mormonism’s divine symbols should not serve as exemplary models for out total gendered, individual, familial, and communal identities and experience is about as unMormon as you can get.” Are you saying that it’s a betrayal of Mormonism to view God as part of an exalted couple instead of as an exalted individual who happens to in a couple? I don’t see why. Must He be both? Must every husband mimic HF and every wife HM? If anything, that not only seems to reinscribe the status quo (barring future revelations on HM), but to enforce it as a norm upon all Mormon couples.

By offering the reading of the status quo as a personal quirk, I seek to offer no definitive theology. It’s a possibility that at once leaves room for future revelation on Heavenly Mother (which could change our image of Her) and frees Mormon wives and mothers from having to model themselves after an absent, silent heavenly exemplar (and single Mormon women, too!).

” If we strive for exaltation, we must realize that individual gendered models will not get us there; it will be as bigendered couples that we arrive.”

That’s somewhat of a stretch. I see no evidence in LDS theology that we arrive as bigendered couples. We arrive as individuals with an eternal gender identity (at least that is how it has been construed in traditional Mormon theology) who have been sealed together into a familial framework. In addition, holding up this final sealing process as exemplifying the whole of what it means to gain exaltation fails to account for the fact that all of the “essential” ordinances and principles followed to get to that point were as individuals. In other words, I think you’re selling the “individual” side of LDS theology short.

“I’m confused by your assertion that “the notion that Mormonism’s divine symbols should not serve as exemplary models for out total gendered, individual, familial, and communal identities and experience is about as unMormon as you can get.” Are you saying that it’s a betrayal of Mormonism to view God as part of an exalted couple instead of as an exalted individual who happens to in a couple?”

I’m saying that concepts of the divine in Mormonism have always been about modeling both individual and familial idealized behaviors and identities. When it comes right down to it, that’s what makes them meaningful and allows people to relate to them. To say that people should love something that they cannot fully relate to is an oxymoron.

What I’m asserting is not particularly novel or insightful. It’s just that this is how deities (most often) function phenomenalogically in cultures. This is reflected well in Mormonism in the very names by which we refer to our divine symbols, Heavenly Father, Heavenly Mother, the Son. We obviously don’t worship them or refer to them as the “Monad” or “Dyadic Couple”.

“Must every husband mimic HF and every wife HM? If anything, that not only seems to reinscribe the status quo (barring future revelations on HM), but to enforce it as a norm upon all Mormon couples.”

Mimic is perhaps not the right word, too strong of a word. In my view, as long as we retain anthropomorphic symbols for the divine, we should seek to allow HF and HM to exemplify our total gendered, individualized, and familial identities as experienced in the real world. This doesn’t reinscribe the status quo but actually indicates quite strongly that our symbols need to change to be relevant.

Thanks for clarifying what you were trying to do with this post. I glad that you leave room open for further revelation.

“I see no evidence in LDS theology that we arrive as bigendered couples. We arrive as individuals with an eternal gender identity (at least that is how it has been construed in traditional Mormon theology) who have been sealed together into a familial framework.”

I don’t see the difference. If a person cannot be divinized as an individual, s/he is divinized as a member of a couple; only couples can be divinized. And sure, all the other ordinances are individual (sort of; I would argue that certain language means the endowment is communal AND individual), but those are not sufficient for exaltation. Besides, we seldom have a problem with people underemphasizing individualist aspects of Mormonism; quite the contrary, to our detriment. If I sell individualist assumptions short, I do so to question frameworks of discourse that I think are too prevalent, too unquestioned, and often ignore fundamental parts of Mormonism (like the idea of Coupled Gods). I don’t mind selling the individual side short.

“To say that people should love something that they cannot fully relate to is an oxymoron.”

This reveals a fundamental difference in our ideologies. I see loving and understanding someone/thing whose experiences you have not (and could not have) lived to be the apex of spiritual attainment, the achievement of which is the essence of Godhood. Of course, it’s impossible as limited human beings; that is where Christ’s grace can, and must, help us.

“We obviously don’t worship them or refer to them as the ‘Monad’ or ‘Dyadic Couple’.”

Sure. I’m fine with saying that without being worthy of divinization as individuals, HF and HM could not have attained Divine Couplehood. But to what degree are they models? If they are models of gendered behavior, what is the essence of masculinity or femininity? Are there allowed to be different expressions of gender across divinities, or must each gender subscribe to a single essential image? Do we worship them as individuals because that’s how we have learned to relate to people in the post-Enlightenment world? Why not worship them as the Heavenly Couple (in addition to as individuals)? Is previous practice normative?

“In my view, as long as we retain anthropomorphic symbols for the divine, we should seek to allow HF and HM to exemplify our total gendered, individualized, and familial identities as experienced in the real world.”

“Gendered, individualized, and familial identities” do not exhaust the potentialities of identity in the “real world.” Which identities do we favor? How about historical, cultural, ethnic, national, communal, economic, class, institutional, contractual, racial, sexual identities? All these express a part -for some people, probably a much greater part- of our identities other than gender, family, or individuality, and seem to suggest that if HF/HM don’t share these, humans cannot relate to them. Are gender, family, and individual the sole characteristics where differences make it impossible to relate? Are all other identities merely phenomenological while gender, family, and individual identities are ontological? How much of this conception is tailored to our specific time and culture?

“This doesn’t reinscribe the status quo but actually indicates quite strongly that our symbols need to change to be relevant.”

In order to oppose the status quo of Mormon gendered modeling under your view, there needs to be revelation about Heavenly Mother. Under my proposal, we can question the status quo even without further revelation (which would, in truth, be still be welcome).

“This reveals a fundamental difference in our ideologies. I see loving and understanding someone/thing whose experiences you have not (and could not have) lived to be the apex of spiritual attainment, the achievement of which is the essence of Godhood. Of course, it’s impossible as limited human beings; that is where Christ’s grace can, and must, help us.”

I didn’t say that we needed to be able to experience the same things to be able to love someone, just that we need a basis for relating to one another. For example, my children relate to me both an an individual and familial level. They don’t love me because they understand all that I know, but because we are all human and share a range of fundamental commonalities, one of which is our gendered experience of the real world.

“But to what degree are they models? If they are models of gendered behavior, what is the essence of masculinity or femininity?”

Don’t misunderstand me. I don’t think there is any silver bullet when it comes to developing a concept of the divine that would adequately serve people’s instinctual yearning to relate to a higher cosmic power envisioned in anthropomorphic form while at the same time be theologically impervious to any sort of criticism.

If I had my wish, I would rather that our divine symbols be flexible and not strictly essentialized or tightly drawn, allowing for individual LDS to make sense of the divine on their own terms and based on their own lived experience.

“Are there allowed to be different expressions of gender across divinities, or must each gender subscribe to a single essential image?”

Speculation about how gender may function in the heavens is unproductive in my opinion. This something we know nothing about. I think we need to focus on how divine symbols function on earth.

“Do we worship them as individuals because that’s how we have learned to relate to people in the post-Enlightenment world?”

I come from a perspective that has studied ancient Israelite and Near Eastern religion and deity-worship in depth and can definitely say that the practice of worshiping deities as individuals (as well as in groups of various kinds) has nothing to do with the Enlightenment whatsoever. It is as old as religion is itself. In monarchic Judah and Israel, Israelites worshiped a pantheon of deities that included a high god (Father/King), his wife (Mother/Queen), and their children. Each of these deities could be related to at an individual level; prayers and other forms of worship could be directed to Heavenly Father/El, to Heavenly Mother/Asherah, or to Yahweh. But they could also be conceptualized as a larger familial entity (such as the couple or larger pantheon) and worshiped as such

“Why not worship them as the Heavenly Couple (in addition to as individuals)? Is previous practice normative?”

I don’t see how envisioning the couple as divine and godly solves the problem of trying to create divine symbols that will be as inclusive as possible.

““Gendered, individualized, and familial identities” do not exhaust the potentialities of identity in the “real world.” Which identities do we favor? How about historical, cultural, ethnic, national, communal, economic, class, institutional, contractual, racial, sexual identities? All these express a part -for some people, probably a much greater part- of our identities other than gender, family, or individuality, and seem to suggest that if HF/HM don’t share these, humans cannot relate to them. Are gender, family, and individual the sole characteristics where differences make it impossible to relate? Are all other identities merely phenomenological while gender, family, and individual identities are ontological? How much of this conception is tailored to our specific time and culture?”

Like I said, I don’t think there is a perfect answer to the problems you raise. I think conceptions of the divine are cultural constructions and so I’m in favor of cultures adapting them to their needs and spiritual and intellectual sensitivities.

“Under my proposal, we can question the status quo even without further revelation”

Good luck with that! Many Latter-day Saint women are currently yearning for more knowledge about a Heavenly Mother and one of the primary reasons is to have a divine personage that they can fully relate to and try to embody in their lives.

I think this is a rather important article for a few reasons. First, it directly addresses that basically our doctrine on women included in exaltation at all comes from sort of imposing a notion of biological requirement on creation of souls. In order for there to be spirit children, there must be a mother, right? Because this is what biology teaches us. Yet, all the examples of creation that include Gods in the scriptures feature a system that is NOT at all bound by the usual biological requirements of creation: Adam and God created Eve, and the virgin Mary brings forth a son. So, if men and women in exaltation are *not* bound by biological requirements, does this mean

1. that there is no basis at all for the exaltation of women and we are really sublimated servants with no future and we might as well kill ourselves now because there is no escape from non-sentiousness and we might as well become worthless in luxury.

2. that biology never was the basis of our exalted community but in fact we are meant to combine as God created us– whatever manner God created us– so that we form equal partnerships with the souls we invest in, with Heaven as a great community of the exalted?

I don’t feel you understood my point at all.

Besides that, I wouldn’t necessarily reduce gender to reproductive capacity. There might indeed be things that distinguish the sexes/genders from each other, even if in this life we might have no idea what those are, really.