I work up close and personal with disability every day. When people found I was going into child neurology their first question was often, “why?” I often hear about how it’s too sad or too depressing.

Fellow physicians struggle with the fact that there often isn’t anything we can do to fix many disorders of the brain such as severe cerebral palsy or neurodegenerative disease, to name a few. Most physicians are by nature fixers and have little patience for the unfixable. Child Neurology is a little different that way. While certainly there is much more we can treat than most people realize, we do have to be comfortable with the cases that all we can do is work to make a child as comfortable and as functional as possible. At times that comfort and functionality seems very small. There is a part of human nature that makes us shrink from the deformed and debilitated. We all have that voice in our head that’s instinctively says, “eeww.” Becoming a physician for these patients involves experiencing this feeling, acknowledging it and then somehow moving beyond.

These children are blaring reminders of our limitations, of failure. Many physicians and residents I have met feel the means used to maintain their health are cruel, unnatural and a waste of resources. As a medical student I had occasion to run into a Mother who had adopted 4 or 5 children with extreme brain injury with very little function, requiring feeding through a tube in the stomach and breathing through a tube in the neck because of inability to swallow or hold the throat open. They were nonverbal and there was reason to doubt they were conscious of much at all. The Neurosurgeon referred to this woman as the patron saint of lost causes. It was puzzling to try and understand exactly what made her do the things she did to the point of it dominating and defining her life.

More than once I have heard disgust tinge the voices of other residents in talking about such individuals. On one occasion there was a patient in the ER for his 5th or 6th episode of pneumonia, a common occurrence in patients who can’t swallow. It tends to become more and more frequent in these patients leading inexorably to their passing away as if circling the drain. We treat infection after infection to try to delay the inevitable. As one resident physician came to see the patient once again for admission to the hospital, they just blurted out in disgust to their mother “What are you getting out of this!?”

I think Bono of U2 fame had an insight, inspired by the case of a child written off similarly, but who’s mother never gave up on him. He later gained movement with the aid of a new medication, a so-called miracle drug, enough to communicate with the outside world for the first time and give us a glimpse of his inner world. He even published a book of poetry. In the song, Miracle Drug from the album How to Dismantle an Atomic Bomb, Bono writes from the mother’s perspective-

I want a trip inside your head

Spend the day there…

To hear the things you haven’t said

And see what you might see

I wanna hear you when you call

Do you feel anything at all?

I wanna see your thoughts take shape

And walk right out

Freedom has a scent

Like the top of a new born baby’s head

I am you and you are mine

Love makes no sense of space

And time…will disappear

Love and logic keep us clear

Reason is on our side, love…

The songs are in your eyes

I see them when you smile

I’ve had enough of romantic love

I’d give it up, yeah, I’d give it up

For a miracle, a miracle drug, a miracle drug

God I need your help tonight

Beneath the noise

Below the din

I hear your voice

It’s whispering

In science and in medicine

“I was a stranger

You took me in”

The truth is we really can’t know what is in the minds of these patients unable to communicate and bound in a broken shell of a body and brain. I think in some cases it really is quite limited, but in the case of the boy above, our common assumptions turn out to be wrong.

What is left for these parents and patients if we physicians turn away from them because of our discomfort? Who will be left to help bear their burdens, to guide them through the maze of their care? it is this question that gives me a glimpse into the motives of one who would adopt and care for so many so broken. I now realize I am not so different from the lost causes’ patron saint. The parents of my patients are some of the most courageous people I have ever met. My patients, even some of the most debilitated, can find such joy and gratitude in the smallest of gifts. They return a smile anytime they are met with one. More than one person like surprise poet above, with body broken but faculties surprisingly intact, has noted that we the “abled” often far overestimate their suffering. With good care they can be quite comfortable. The parents that give this care are angels of mercy and their service often takes over their life. Who am I to call into question a sacrifice like that?

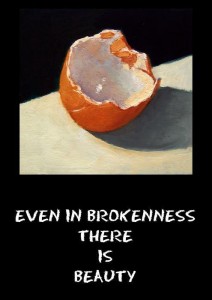

Much of the discomfort we feel seeing them is inborn in us. Evolutionarily, we reject the broken specimens for the benefit of our species in a brutal world that demands survival of the fittest. This is the natural man. We are built to reject imperfection and see only limitation. When we recognize this, we may move past it to see something wonderful beyond it- beauty in brokenness.

In Mormon culture there is a lot of folklore attempting a theodicy to explain why these children exist. What are they getting out of mortality? It is tempting to dip into premortal existence for answers. It is very popular to suggest that these children were the noble and great ones, so far along they don’t need the “full” mortal experience.

We don’t know, We can’t know if there is any truth to claims of their premortal nobility, but one thing I am intensely aware of is that they grow, develop and learn just as we all do. While they may not be having my mortal experience or your mortal experience, it is undeniable that they are, in point of fact, having a mortal experience.

They often have a certain innocence I love, but that doesn’t mean they can’t learn, they can’t make mistakes, they can’t sin, or that they can’t repent. While these parents and those of us around them do struggle with the seeming injustice of it all, I think this folklore has a danger in that it can saccharinize disability. It trivializes their own purpose and meaning in this life. It leads to patronizing attitudes that stunt the personal growth of children with chronic disease. The fact is that they are here, fully mortal and fully human, and I believe it is for their own experience and good as with any of us.

Disabled children of all forms can end up with “vulnerable child syndrome” remaining forever an infant, never learning their own survival skills or moving beyond infancy and total dependency, not because of a lack of potential, but because of a lack of parental or societal capacity to imagine it at times. Parents have a deep set natural fear response triggered when a child is born that struggles, maybe even comes close to death at an early age. That fear can cause an inability to give the child any independence.

As Latter Day Saints, I believe our primary goal for the disabled has to be helping them grow, develop, gain agency and self sufficiency as much as humanly possible. I sincerely believe that they, like all of us, have a divine potential within. When I look at the difference in agency or ability between myself and them and then compare to the massive gulf between me and God, the difference seems small indeed. The fact is in all but the absolute most severe cases, they are progressing too, regardless of limitations.

We need to fight the inclination to lower expectations and never shut a door until we have to. Until we know what can or cannot happen, we should always ask ourselves “why not?” Why can’t this individual do whatever we would normally do? Why can’t they become a parent? Why can’t they date or socialize with the rest of us? Why can’t they live on their own and manage their own life? Furthermore, what can we do to help them? What can be done to enable them to commute, to shop, to navigate their way through education and vocation?

We need to fight the inclination to lower expectations and never shut a door until we have to. Until we know what can or cannot happen, we should always ask ourselves “why not?” Why can’t this individual do whatever we would normally do? Why can’t they become a parent? Why can’t they date or socialize with the rest of us? Why can’t they live on their own and manage their own life? Furthermore, what can we do to help them? What can be done to enable them to commute, to shop, to navigate their way through education and vocation?

These individuals are often capable of great contributions beyond our wildest expectations when they are allowed to. I imagine with joy one beautiful day when they, and we, will be resurrected, restored to a perfect frame. Until then we need to encourage their independence, growth and development. I believe the Zion Society will be one in which all of our weak, our infirm, will be given the tools they need to become one with us. It will be one in which we all support, lift up, and learn from each other. Disability can be minimized and independence maximized through technology, through planning, through minimizing stigma and through the assistance of others. If we have the will, we can start building that society now.

Beautiful post. As the mother of a son with Autism Spectrum Disorder, I greatly appreciate and agree with your points. When he was diagnosed, the projections were dismal indeed, even referring to him as clinically “mentally retarded.” We were aggressive about doing everything that we could, though, so that he could learn and grow as much as possible, to whatever extent that would be, and the strides he has made have been truly amazing. Just a couple months ago, his reading assessment scores (yes — that he even reads at all is a miracle in and of itself) matched those of his normally developing peers. We must never give up on these precious individuals or resign ourselves to some gloomy fate which is, in fact, unknown and unrealized until we have really given it our all.

Emily, sounds like he’s lucky to have you for a parent. That’s wonderful. Thanks for sharing.

I have to admit, when I first started reading this, I rolled my eyes a little. Oh great, another doctor theorizing on what it is like to have a child with disabilities. (My daughter is medically fragile, after being born at 23 weeks gestation).

But I loved this. “Much of the discomfort we feel seeing them is inborn in us. Evolutionarily, we reject the broken specimens for the benefit of our species in a brutal world that demands survival of the fittest. This is the natural man. We are built to reject imperfection and see only limitation. When we recognize this, we may move past it to see something wonderful beyond it- beauty in brokenness.”

Thank you for sharing.

AFKNICK,

You are absolutely right that mine is an experienced observed and not an experience lived. I would never consider my voice more valid that those who live with disability, even if I am one of those obnoxious doctors, full of myself. 😉

It is for that reason that I am so happy you of all people found something of value in the post. It means a lot to me.