“THE WORD IS IN CHRIST UNTO SALVATION”

Were Alma and Amulek Kierkegaardian Existentialist?

Alma’s Discourse to the Poor among the Zoramites: Alma 32:1-33:23

Two links that I highly recommend that will help inform your studies of this lesson:

Mormon Stories Engaging Gospel Doctrine Class podcast click here

KC Kern’s Rational Faiths post that looks at the development of Alma’s faith click here

Some Success Among the Poor: Alma 32:1-6

32:3 I find it odd that Mormon would even call what the Zoramites were doing “worship[ing] God”

Alma2 Speaks of Humility and Belief: Alma 32:7-20

Alma 32:8-33:23 May have been been either reported verbatim or significantly edited or even reconstructed by Mormon. (Grant Hardy, Understanding the Book of Mormon, A Reader’s Guide, pg. 105)

32:16 “…blessed is he that believeth in the word of God…without being brought to know the word, or even compelled to know, before they believe…” Within the LDS culture, I am concerned that the emphasis on “knowing”, is done so to the detriment of “belief” and “faith”?

Questions are good. Doubt is not the opposite of faith, but absolute, antiseptic certainty is the opposite of faith. (Phillip Barlow, professor and holder of the Leonard J. Arrington Chair of Mormon History and Culture at Utah State University, Mormon Matters podcast; episode 73, “And the survey Says…!” 1:08)

32:17 What is the difference between asking for a sign and asking for an answer from God?

Alma2 Describes an Experiment in Faith: Alma 32:21-43

32:24 “…judge you only according to that which is true..” Of what “truth” is Alma speaking?

32:28 “Faith is like a little seed: If planted it will grow.” (Faith, Children’s Songbook, pg. 96) Sorry to tell you, that’s not what Alma taught. The seed is “the word”.

32:28, 35 In these two verses, Alma uses the words “true” and “real” in non-traditional ways. What does he mean with the way in which he uses these two words?

32:33, 40, 42 “…and your faith is dormant…looking forward with an eye of faith…because of your faith…” Are these two different types of faith? One gets you to “perfect knowledge” the other “nourishes” that knowledge? “Dormant” suggest the that the faith is still there, but not active; interesting I think. “looking forward with an eye of faith” would suggest that despite “your knowledge [being] perfect” (vs.34) faith is still required.

you to “perfect knowledge” the other “nourishes” that knowledge? “Dormant” suggest the that the faith is still there, but not active; interesting I think. “looking forward with an eye of faith” would suggest that despite “your knowledge [being] perfect” (vs.34) faith is still required.

32:43 “…ye shall reap the rewards of your faith, and your diligence, and patience,….” No mention of knowledge here.

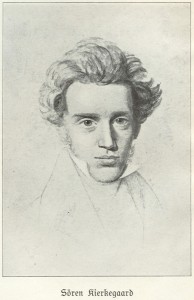

The existentialist philosopher, Soren Kierkegaard, the existentialist philosopher, rejected the need to point to evidence for God. For Kierkegaard, a person’s need for objective proofs of God is a clear sign that the person’s faith is lost. To strive to place a rational foundation under your faith removes the demand for inwardly grappling with the paradox of living religiously. Kierkegaard was also dismissive of a trend towards using historical evidence to prove Jesus’s validity. He believed that these attempts demean faith and have a common goal: relieving the task of taking responsibility for your faith and placing it on something external, like reason and intellectual analysis (Christopher Panza, PhD & Gregory Gale, MA, Existentialism for Dummies, pg. 230).

Was Alma a Kierkegaardian existentialist?

Alma2 Quotes Zenos on Prayer: Alma 33:1-11

Although Mormon, as the narrator, never inserts scriptural passages, he does recount how Abinadi recited the Ten commandments and Isaiah 53 (Mosiah 13-14), how Alma2 quoted Zenos and Zenock (two extra-biblical Hebrew prophets) in his sermon to the Zoramites at Antionum (Alma 33), and how Jesus quoted Isaiah, Micah, and Malachi (3 Nephi 20-22, 24-25) (Hardy, pg. 299, note 5)

33:1 “…desiring to know whether they should believe in one God…” In the previous chapter it was “the word” that is to be planted (Alma 32:28). In The Gospel of John, “the Word” (logos) is the Son of God. Are Alma and Mormon suggesting that our faith should initially be in God? And that when our “knowledge is perfect in that thing” “That thing” is God?

33:2 How does Alma, referring back to the idea that God can be worshipped anywhere, answer the Zoramites’ question? Is the answer found in the prayer of Zenos when he refers to the “Son” of God, suggesting that there is a God the Father and a God the Son (vs. 11, 14, 16, 18)?

Alma2Quotes Other Prophets Who Have Spoken of Christ: Alma 33:12-23

33:19 “Behold, he was spoken of by Moses…” Perhaps this is a reference to Moses 1:32-33; 5:7-9; 8:24.

33:12-23 The basic message being taught here is exercising faith unto repentance and being forgiven through Jesus Christ’s sacrificial atonement. The basic message was taught by King Benjamin (Mosiah 3:16-33), Abinadi (Mosiah 15:1-9; 16:1-15, Alma1 (Mosiah 18:7-16), and earlier by Alma2 (Mosiah 27:23-31; Alma 5:14-32; 12:22-27).

33:15, 16 Zenos and Zenock were Old World prophets whose writings had been preserved in the Brass Plates; compare 3 Nephi 10:15-17 with 1 Nephi 19:10-12. One wonders if there was additional information about these men included in the lost 116 pages. Apparently the two prophets were ancestors of Lehi (3 Nephi 10:16), which may explain how their words got into the Brass Plates. The collection was a lineage record of some sort, complete with genealogies (1 Nephi 5:14-16) (Hardy, pg. 312, note 20)

33:20 “Now the reason they would not look is because they did not believe that it would heal them.” Compare to 1 Nephi 17:41; Numbers 21:6-9.

33:23 “…plant this word…” This strongly suggests that the seed is Jesus Christ.

[This is the end of Alma2‘s Discourse to the Poor Among the Zoramites: Alma 32:1-33:23]

Amulek’s Discourse to the Poor among the Zoramites: Alma 34:1-41

Amulek Explains the Plan of Redemption: Alma 34:1-16

34:1-16 The basic message being taught here is exercising faith unto repentance and being forgiven through Jesus Christ’s sacrificial atonement. The basic message was taught by King Benjamin (Mosiah 3:16-33), Abinadi (Mosiah 15:1-9; 16:1-15, Alma1 (Mosiah 18:7-16), and earlier by Alma2 (Mosiah 27:23-31; Alma 5:14-32; 12:22-27; 33:12-23)

34:2 compare with Alma 30:59; 31:1

34:6 “…the word is in Christ…” Aha! We have answered our question. Mormon, Alma, and Amulek now make a clear connection between “The Logos” (The Word) and Jesus Christ being the logos.

34:6, 8 “…my brother has proved unto you…I do know…” Would a more correct word be, instead of “proof”, be “evidence”? And, are there different kinds of knowledge and truths?

Now for a little more existential philosophy:

When someone says, “The moon circles the earth,” he makes a claim about objective reality or about what things are. What makes the sentence true is objective reality itself. Is the situation in the objective world just like the sentence says it is? In other words, does the moon really circle the earth? If it does, the sentence is true; it if doesn’t, it’s false.

Note, however, that this way of talking about truth seems to deal exclusively with objects. or with what things are. For most inquiries, this kind of truth, dealing with what things are – or what the existentialist philosopher, Soren Kierkegaard calls objective truth – is perfectly appropriate. Most of the time, you want to know whether “the tornado is heading this way is big” or whether “the water is boiling.” In these cases, all you want to know is whether the sentences you’re using map onto the world around you.

Whether an objective truth exists doesn’t require any personal involvement on your part. Being detached from the situation doesn’t create a problem. For example, claiming that “water is boiling” is true can be verified by observing (in this case visually) whether the object (the water) referred to in the sentence really has those properties (boiling). If so, the statement is true. What would your involvement add? After all, if the water is boiling, that’s true independently of you. So the issues of you and your life and existence of objective truths about things are entirely separate from on another.

Most of the time, people want this separation to be the case. Think of science. Science is supposed to give you knowledge about the truths of the world that you live in. You don’t want those truths to depend on the existence of the scientists or on anyone in particular. If chemical XYZ is bad for your health, you want that to be a fact that’s independent of the personal existence of everyone. You want it to be a brute, impersonal truth you can count on.

But think this belief through for a moment. If one kind of truth pertains to the existence of objects, does another kind of truth pertain to the existence of subjects (subjective truth)? If so, truth can actually exist in a way that is completely independent of science. Because subjects are defined by how they exist, a notion of subjective truth would have to take the engagement of the person into question. As such, these truths wouldn’t be independent of you because their very existence would require your own deep involvement in the world.

Most people are positivists, which means that they accept one kind of truth- the kind that science prizes. If science can’t authenticate something, the positivists say, it’s not worth talking about because it’s just nonsense. The existentialists, however, reject positivism. Instead, they claim that the way that we talk actually reveals that we believe in another type of truth, which Kierkegaard called subjective truth. These truths relate to the kind of how (subjective) existence that human beings possess as living, engaging subjects. The existentialists think that when we say that we must dedicate our lives to truth, subjective truth is what we really mean.

To highlight the two different kinds of truth, it’s helpful to think about the different ways that you use the verb know . The connection between knowing and truths is a tight one; if you say that you know something, you mean that you’re in some way connected to the truth about that item. Different ways of knowing imply different types of truth. With this in mind, think about these two ways the verb is used:

- You claim that you know that God is X, Y, Z.

- You claim that you know God.

What’s the difference? In the first example, you know that God is this or that. Perhaps you know that God is good, or that God is all-powerful, or something of that sort. You’r claiming that some sentence like “God is X” is true because what it claims exists externally to you. If God is omniscient, for example, that’s truth independent of you and independent of whether you know it to be true.

How do you come to know these kinds of truths? The method is pretty straightforward. You look at the sentence and then you look at the object. You notice through distanced observation that they match. In the end, you, as a subject have nothing to do with whether the sentence is in fact true.

Now think about the second use of the verb know, which is very different from the first. When you say you know God, you’re not implying that you’re comparing sentences with objects and seeing whether they match. Instead, you’re claiming that you’re in a relationship with God, that you’re involved with God in some way. “Knowing God” in this sense has a meaning like “living life intimately with God as your co-pilot” or something very much like it. “Knowing God” means letting God inform the way that you live. Clearly, this kind of truth isn’t independent of you!

So what does truth mean in this second sense? Instead of comparing sentences to objects, subjective truth compares ways of coming at life with the existence itself. As Kierkegaard puts it “What is truth, but to live for an idea?” As such, for a subject to exist in the truth means to have a cause or ideal worth dying for and to passionately engage with life through it. When your ideal is worth dying for, and when you’re related to it in the right way, truth is embodied in the way that you live your life.

In fact it is the “subjective” truth and knowledge that give us meaning, not “objective” (scientific) truth. Living in truth means not being motivated to pursue that idea on the basis of objective evidence or proofs. In fact, Kierkegaard is adamant about one thing: The more you can prove the objective reality of your ideal, the less passion you attach to it, and the less it seems worth pursuing. As a result, the more assured you are about the objective truth of the ideal, the less subjective truth will be embodied by pursuing it. Similarly the more you pursue evidence for your ideal, the more it will appear that you lack passion about it.

Thus lies the heart of one sense of paradox at the core of subjective truth. Living in the truth or with passion requires firmly embracing and committing to ideals that you keep in a state of uncertainty. Passion requires not knowing whether that ideal is objectively true. As Kierkegaard puts it, “Passion and the paradox fit each other perfectly.” Here, you see Kierkegaard’s attempt to link a dimension of truth to his requirement that a truly passionate life requires uncertainty and risk. Truth and passion require mystery. Kierkegaard thinks passion requires embracing the uncertainty of what you pursue. He thinks you must make the truth yours alone by appropriating it and allowing it to transform your identity and your life. Kierkegaard famously said, “Here is such a definition of truth: an objective uncertainty held fast in an appropriation process of the most passionate inwardness is the truth, the highest truth attainable by the individual.” (Christopher Panza, PhD and Gregory Gale, MA, Existentialism for Dummies, pg. 143-146)

In 1974, Thomas Nagel, a philosopher who studies the mind, posited an interesting thought experiment. What if, he wondered, you knew everything there was to know about the physical scientific facts involved when a bat uses echolocation? In such a scenario, he asked, would you know what it was like to use echolocation? Nagel’s answer is no – that the actual experience specific to bat life couldn’t be fully reduced to the sorts of facts that science collects, even if it had them all to study.

Think about it. If you agree with Nagel’s conclusion, it seems to suggest that what it’s like for you to exist, experience the world, or participate in life can’t be understood from the outside through scientific investigation (what Kierkegaard would call objective truth). Instead, because knowing what it’s like to be a bat would require being a bat, you have to take seriously the actual inside experiences of the human being. Knowing what it’s like to participate in human life requires looking at human life from the inside and seeing how it ticks on its own terms. (Panza, pg. 116)

Science can tell us how a bat hunts, but that tells us nothing of what it actually is like to be a bat; it give us no meaning. Similarly, science can tell us how hot it is outside by looking at a thermometer (objective truth); this also provides us with no meaning. Think of the following statements, “I know it is 99 degrees outside,” vs. “I know God.” The first is what the existentialist would call “objective truth/knowledge.” The latter is what would be called by the existentialist “subjective truth/knowledge.” The former (I know it is 99 degrees ) provides us with no meaning, while the latter (I know God) does.

34:13,14 The teaching found here was taught earlier by Nephi in 2 Nephi 25:24; Reiterated by Abinadi in Mosiah 13:27,18; by Alma in Alma 25:15,16; 30:3; and later by Mormon himself.

Amulek Urges the Zoramites to Pray: Alma 34:17-29

34:27 “…let your hearts be full, drawn in prayer unto him continually for your welfare…” I was having a discussion with a good Muslim friend of mine. By good, I mean – he is a good person and he is a good friend. We were discussing prayer. He asked me if I prayed at the beginning of each of my surgical cases. I told him no. He asked why. I told him because I did not want to pray vocally in front of everyone for I did not want to appear self-righteous and draw attention to myself. He said that I can say a silent prayer to God and no one would know.

34:28, 29 These verses remind me of James 1:27 “Pure religion and undefiled before God and the Father is this, To visit the fatherless and widows in their affliction and to keep himself unspotted from the world.” I worry when our dogma becomes so central to our religion that we forget what James said and what Amulek said: “I say unto you, if ye do not any of these things [giving to the poor] , behold, your prayer is vain, and availeth you nothing, and ye are hypocrites who do deny the faith.” I believe that we would be hypocrites because we are asking for help but not offering any.

Amulek Urges the Zoramites to Repent: Alma 34:30-41

34:34 “…for that same spirit which doth posses your bodies at the time that ye go out of this life, that same spirit will have power to posses your body in that eternal world.” I have recently started wondering if this teaching is unique to Mormonism or if other faith traditions also carry the same teaching.

Compare what Amulek says in Alma 34:35,36 with what King Benjamin says in Mosiah 2:36, 37. Amulek is using the language of King Benjamin to teach the dissident Zoramites.

34:35 “…and he doth seal you his…” I know it would be anachronistic to assume that the sealings we do in the temple have the mirror opposites in regards to Satan’s sealing as found in this scripture. Yet, I find this scripture to be particularly provocative when I think of it in that light.

An ominous contrast (to Alma 34:35) is with a section of King Benjamin’s speech, where he had promised the righteous that it would be Christ (rather than the devil, as Amulek’s admonition) who would “seal you his.” (Mosiah 5:15). Of course, we can perceive these kinds of repetitions, contrasts, and variations only because Mormon chose to insert Benjamin’s discourse into his history as an intact document. And if problems later appeared with “many of the rising generation that could not understand the words of King Benjamin, being little children at the time he spake unto his people” (Mosiah 4:26), a phrase that Mormon himself uses in recounting Alma’s preaching at Zarahemla (Alma 4:13), along with the “retaining a remission of sins” (Alma 4:14; Mosiah 4:12, 26) (Hardy, pg. 133)

34:36 compare with Mosiah 2:37; Alma 7:21

34:36 “…and he has also said that the righteous shall sit down in his kingdom, to go no more out, but their garments should be made white through the blood of the Lamb…” The origin of this quotation is uncertain, but Alma2 is quite fond of it. See Alma 5:24; 7:25; 29:17; 38:15. Cf 1 Nephi 12:10, 11. “Sit down …in the kingdom of God/heaven.” originates with Matthew 8:11 and Luke 13:29, but the phrase is not pervasive in the Book of Mormon; rather, it seems to have been a favorite of Alma’s. The exception would be what we find in Alma 34:36 in which the phrase comes from Alma’s companion, Amulek; Mormon uses the phrase in Helaman 3;30; and Jesus uses it in 3 Nephi 28:10.

[End of Amulek’s Discourse to the Poor among the Zoramites: Alma 34:1-41]

Repentant Zoramites Are Cast Out: Alma 35:1-9

35:2 gives the impression that Alma and Amulek were preaching to a mix crowd of both the poor and the “popular”. However Alma 32:5-7 gives the impression that the crowd consisted only of the poor.

Grant Hardy notes:

Occasionally there is tension between Mormon’s desire to tell an edifying story and his commitments to accuracy. He believes the facts of history will demonstrate moral principles, but the messy details of the past can get in the way of clear, unambiguous lessons. Embedded documents offer one way of avoiding inconvenient truths while at the same time fulfilling his obligations as a historian. They allow him to present a few significant particulars without having to comment upon them directly.

[In the previous chapters and in this chapter, we have sermons] by Alma and Amulek, with the result that many of the poorer Zoramites repent and are consequently expelled from the city. They make their way to the land of Jershon, where they are welcomed and given land (Alma 32:1-5; 35:1-7). The Zormaites are so angered by the hospitality of the Nephites in Jershon that they form an alliance with the Lamanites to attack them (the very scenario that Alma’s preaching was intended to prevent). Next we read that “thus commenced a war betwixt the Lamanites and the Nephites…and account will be given of their wars hereafter” (Alma 35:13; note that the combined Zoramite/Lamanite forces are now simply referred to as “Lamanites”).

Mormon quickly observes that Alma and his companions returned home to Zarahemla and that their new converts were forced to take up arms to defend themselves (35:13), and then he begins a rather lengthy digression: “Now Alma, being grieved for the iniquity of his people, yea for the wars, and the bloodsheds and the contentions which were among the people, and having been to declare the word…among all the people in every city…therefore, he caused that his sons should be gathered together, that he might give unto them every one his charge” (35:5-16). After seven chapters copied from Alma’s personal record – consisting of Alma’s eloquent speeches of counsel to his three sons – Mormon tells us that Alma and his sons went out to preach again, and then he brings us back to the war that had begun so many pages earlier (Alma 43:3,4; notice again that the conflict has been reduced to Nephites and Lamanites, further obscuring the cause of the invasion).

In other words, Mormon inserts Alma’s instructions to his sons in the middle of the Zoramite War, where it represents a significant break in the narrative. But, since the war itself takes place entirely within the eighteenth year, with no discernible impact from the new round of preaching, Mormon could have recounted the Zoramite affair from the beginning to the end and then added Alma’s document without upsetting the chronology at all. In fact, under this arrangement, Alma’s teachings would have concluded his term as record keeper (Alma 44:24) and would have led quite naturally into his last words and death (Alma 45), the place where we typically would expect final words of fatherly wisdom (as in 2 Nephi 1-4). The surprising placement seems designed to disrupt a smooth reading of the Zoramite story, which, taken as a whole, did not go so well. By the time readers get back to the war, they may have forgotten the rather awkward truth that Alma’s preaching to the Zoramites not only did not prevent hostilities but was itself a major catalyst for the fighting (upon his return to the main narrative, Mormon quickly adds additional factors; Alma 43:5-8). Yet all the facts are there, even if the sequence of causation is obscured. Technically, Mormon acquitted himself as an honest historian, but he has also managed to divert our attention from some awkward details. (Hardy, Reader’s Guide, 148-150)

In a foot-note Grant Hardy states: One possible connection is that when Alma addresses his youngest son, Corianton, he speaks at length of death, judgment, and resurrection – issues that the rebellious Corianton had been worried about. This discourse is particularly poignant given that Mormon has placed it at the beginning of the Zoramite War; before the year is out, a large number of young men are going to be dead (Alma 44:21-24) (Hardy, Reader’s Guide, pg. 305, note 51)

The Zoramites Ally Themselves with the Lamanites: Alma 35:10-15

35:13 “…and an account shall be given of their wars hereafter.” Grant Hardy calls this editorial interruption by Mormon an “editorial promise”. The promised account is given in Alma 43:3-44:24.

35:13

Unlike Nephi and Moroni, Mormon employs an explicit, a strict chronology, particularly after the end of the monarchy in 91 BC, when events are precisely dated according to “the X year of the reign of the judges” (though stories taking place in Lamanite territory have many fewer chronological markers e.g., Mosiah chs. 9-24 and Alma chs. 17-27). Almost every year is mentioned individually, even if Mormon does not give them equal coverage. Sometimes nothing of note seems to have happened and a year is passed by in a sentence or less. Often, however, the dates come in pairs as Mormon indicates both the beginning and ending of a particular year. These references can be separated by only a few verses, but frequently they are several chapters apart. (.g.g, 83BC, the eighteenth year of the reign of the judges, begins at Alma 35:13 and ends at 44:24). Most of the time, readers who are paying attention will know exactly when a particular incident took place, and there is a sense of momentum that builds when the year markers come faster as the narrative gets closer to Jesus’ appearance among the Nephites. (Hardy, Reader’s Guide, pg. 103)

There is, however, a discrepancy when we try to correlate the standard Western calendar with that of the Nephites. They counted six hundred years from the time Lehi left Jerusalem to the birth of Jesus (1 Nephi 10:4, 19:8; 2 Nephi 25:19; 3 Nephi 1:1), yet Lehi fled in the first year of the reign of Zedekiah (1 Nephi 1:4) or 597 BC, while Jesus was born no later than 4 BC. Latter-day Saints have dealt with this problem in several ways, including speculations that the Nephites used a shorter, lunar calendar. See John L. Sorenson, “Comments on Nephite Chronology,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 2,2 (1993): 207-11; and Randall P. Spackman, “The Jewish/Nephite Lunar Calendar,” Journal of Book of Mormon Studies 7, 1 (1998): 48-59. (Hardy, Reader’s Guide, pg. 297, foot note 15)

35:14 The two sons of Alma are Shiblon and Corianton. See Alma 31:7.

35:14

In a moment of crises that predated the Nephite Reformation (when he fought face-to-face with Amlici), Alma prayed that he might “be an instrument in [God’s] hands to save and preserve this people,” a request that was apparently granted (Alma 2:30-31). And then several years later, after he had preached to the Zoramites at Antionum alongside the sons of Mosiah, the entire party was described as having been “instruments in the hands of God of bringing many of the Zoramites to repentance.” (Alma 35:14) (Hardy, Reader’s Guide, pg. 309, note 30)

[ End of Alma2‘s Mission to the Zoramites: Alma 31:1-35:14]

Alma2‘s Testimony to His Sons: Alma 35:15-42:31

Introduction to Alma2‘s Testimony: Alma 35:15, 16

35:16 “…according to his own record.” Mormon is going to insert into his history the texts of three speeches that Alma directed toward each of his sons (Alma 36-42). Which Mormon tells us right off-the-bat, will be in Alma’s own voice.

Since Alma 36-42 are written in the first-person narrative style, it appears that Mormon2 has copied Alma2‘s own account directly into the text. (Grant Hardy, The Book of Mormon, A Reader’s Edition, foot note pg. 353)

Excellent quote by Phillip Barlow (32:16).

Phillip Barlow is a frickin’ genius. That quote has given me a lot of strength because it is so true! Kylan Rice also used it in his most recent post, “The Day Breaketh”.

http://rationalfaiths.com/the-day-breaketh-2/

Paul and I are going to the Sunstone Symposium this year. Brother Barlow is going to be one of the many presenters. I hope we get to attend his lecture.

I skimmed all of it, and closely read parts of it. A few things stuck out to me:

1. I have long held Alma as a ‘Kierkegaardian’ Existentialist. You should also check out the book of Ecclesiastes with that mindset, it’s pretty ace.

2. The section where you talk about different uses of the word ‘know’ is rather fascinating to me. As you go on to talk about how knowing something objectively doesn’t bring fulfillment/ knowing something subjectively does, it reminds me of the divide between the classic and the romantic. The classic pertaining to objective/detached knowledge, and the romantic clearly being its counterpart. The idea is quickly laid out in C.S Lewis’ short piece Meditations in a Tool Shed, and in much more depth in Robert Pirsig’s book Zen and the Art of Motorcycle Maintenance. If you’re hip to the jive, I’d definitely suggest checking out both pieces, they’re very quality. Although I would suggest C.S Lewis’ work first, as is a simpler description and explanation of what Pirsig talks about. 🙂

Maygan,

Yes I’m hip to the jive.

I’m not sure if you listened to the Mormon Sunday School podcast that I linked to or not. In the podcast, Kristine Haglund provided a perspective to the metaphor of the seed and it growing that spoke to me. Paraphrasing her, she essentially said: That a plant almost never grows linearly. It often grows to the side or meanders around. Sometimes the plant dies. When it dies, it fertilizes the soil and allows us to plant a new truth. Amazing insight I thought.

For me, faith is much more organic than how the present rhetoric usually is in church. We usually use Moroni 10:3-5 as a witch-hazel stick for diving truth; pray, and the truth of the issue will come. Alma and his metaphor of a seed and it growing seems to be more truth to life. Like I said, it is more organic and allows for more diversity of experience.

Great post, Mike. I like Kierkegaard the more I hear about him, and I’m glad to see “Existentialism for Dummies” finding its way in the discourse – especially in a religious/spiritual context. I would love to see more thought on the intersection between existentialism and religion, particularly as they occupy rather polar zones in my mind. This was an artful integration, though.

A few thoughts:

“Sorry to tell you, that’s not what Alma taught. The seed is “the word”.”

Excellent. I had never paid too much attention to the disparity between the primary teaching and the actual scripture, but this is a refreshing correction. It’s confusing to me to imagine faith “growing”. Though faith certainly exists as a relative spectrum, I think this is a rare either/or situation–we either have faith or we do not. I don’t think the “amount” or “size” of faith factors into the equation at all. Faith is important in itself. Certainly we inevitably obtain faith IN, say, diety or certain aspects of the gospel; however, the straight-up notion of faith, and just having some of it, is the real key to drawing closer to God in heaven.

“Are Alma and Mormon suggesting that our faith should initially be in God?”

Interesting. If that’s is the case, I don’t think most members of the church operate this way. This is an interesting article from a publication that I think you’d be interested in for its own sake:

http://www.firstthings.com/article/2012/01/mormonism-obsessed-with-christ

Mormonism is a startlingly Christ-“obsessed” faith. Huge emphasis is placed on “mediums” or “intercessors” – we see pangs and echoes of this all throughout the historical narratives of the church and its scriptures, and in the bedrock doctrine. The theme of translation, for instance, implies the need for a translator, or a medium between original text and final comprehension. I don’t think that most members have faith initially in GOD, but rather in Christ. Could be wrong though.

“Clearly, this kind of truth isn’t independent of you!”

I loved this passage, in which you discuss types of truth. I love the notion that “knowing God” isn’t having him figured out necessarily, or knowing that he exists at a certain set of coordinates in space. Rather, knowing God is an involvement with him. WE must be apart of the equation. If I’m a humanist, I’m a humanist in this sense: spirituality is about the individual. Truth – subjective truth – is an internal construction. Beautiful.

Thanks again, Mike. I had a few other points, but I’m out of time.

Kylan

Kylan,

As you know, I first became interested in existentialism because people were always using the word “existentialist”, but I had a gut feeling that they weren’t using the word correctly. It’s similar to how a medical assistant that use to work with would say everything was “proverbial”. I couldn’t find the definition forever because I was looking up the word “perverbial” – because that is how she was pronouncing it! Needless to say, she wasn’t using the word correctly, nor were most people using the word “existential” correctly.

To paraphrase a story I heard paraphrased: A young Christian man was asked why he was was studying existentialism in college. His answer, “I want to know what the enemy is thinking.” An unfortunate response I thought. Recognizing that most existentialists were/are atheists, there was still a lot of truth I found in the philosophy. “God is dead, and we have killed him.” I agree we as a western society have killed God. I also agree that a life devoid of God has no meaning and thus you would be required to find your own meaning. The existentialist rejection of “closed systems” as containing all truth is also very true. This leads to their warning of how many view science as being able to answer all questions; scientism as it is often called. The most powerful truths I found within the philosophy were what Kierkegaard taught about objective and subjective truths; that’s why I included it in my post. It speaks to me. It unpacks so many of the problems I see as hurdles with certain truth-claims of our faith.

Thanks for your thoughtful response Kylan; always expansive.

See you Friday!

Digging this post… and I haven’t even finished reading it yet!

Hi, Alma in the book of mormon declares that faith is a seed, and more over the test of faith is plant it, so is with any belief that we hold to be true, we must plant it or experience in living in our personal experience. Otherwise it could not grow, enlarge our souls or uplift us because all belief’s are static truths. truths that are static have no power to affect our lives if not lived. Then, these truths are dead, not alive. So Jesus Christ an authority on truth has stated, that if we are to have a faith of a seed of mustard, only then will it grow up to be liked unto eternal life. I feel that Christian thinking, even Mormon thinking could develop a stronger faith like purpose in its teaching to allow its members more experiences in true life to blossom with out codifing and embracing it through typical means. We need to always look for ways to perform unselfish service and live within our means and help others without motivation or noteriety. Becoming more faith conscious in purpose and ideas, leads to understanding and meaning and this leads to revealed God within, not without.

Thanks, (to Steven R. Covey) Proactive. thoughts about belief.

from me.

Winston,

Good points. Thanks!

Don’t be a stranger – be sure to swing by again.

Mike