Mosiah chapters 7-11

The story that Mormon tells in chapters 7-11 of Mosiah gets complicated. He uses some unique literary devices that the previous narrators had not used. These include embedded primary texts and flashbacks. Dr. Grant Hardy, Professor of History and Religious Studies at the University of North Carolina at Ashville had the following to say:

“The Book of Mormon, with its multiple records, plates, writers and editors, is anything but a naive, straightforward narrative. This makes it something of a puzzle. If Joseph Smith had intended to author a religious morality tale, either to gain converts or to make money, he could have written something much simpler. Latter-day Saints regard the integrated complexity of the text (especially in light of its oral dictation) as evidence of both its divine transmission and the contingencies of its origins as an actual historical record…The Book of Mormon’s use of embedded documents increases its verisimilitude, and though this was a literary device used in novels, it has also been one of the techniques by which historians have presented the past. Classical historians tended to focus more on speeches than documents, but both Thucydides and Josephus quote letters, and Ezra-Nehemiah includes memoirs, letters, royal decrees and archival materials. In fact, the book of Acts is something of a composited text, with stories, speeches, dialogues, and letters, but the unnamed narrator is much less of a presence than Mormon is in his history of the Nephites. ” (Grant Hardy, Understanding The Book of Mormon, A Reader’s Guide, pg. 121)

Why would Mormon use embedded documents? We don’t know. We have to guess at his motives. Grant Hardy continues:

“We get a chance to exercise our interpretive creativity and then test our hypotheses against close readings of the text at hand. In this way, we gradually construct a coherent picture of our narrator by observing how he handles his sources.”

Some possibilities come to mind. From Mormon’s perspective, the inclusion of letters, sermons, and other writings might give his readers a better sense of the past or more immediate access to events and personalities of long ago. Presenting their voices directly could add variety and drama to his account. Inserted documents could also increase the historical value of his work and give it more of an air of authenticity. Mormon simply may have admired the literary qualities of particular speeches and hesitated to substitute his own paraphrase for their original eloquence. Or perhaps he wanted to give his audience a chance to respond directly to the pleas and teaching of past prophets. And certainly such insertions slow down the narrative and give emphasis to particularly significant incidents. These sorts of motivations probably apply across the board .”(Hardy, pg. 123)

7:1-6 The expedition mentioned here is found in Omni 1:29-30. It sounds like the initial expedition was prior to King Mosiah2 becoming King.

Mosiah 7:1-6 also gives us some indication of Book of Mormon geography. “Go up to the land” can be either interpreted as a cardinal direction, like North, or can mean that Zarahemla was in a valley below (as in sea level) Nephi-Lehi.

7:3 It is odd that it was a native of Zarahemla (a Mulekite) that led the group as opposed to a descendant of Nephi and Lehi. Of course this begs the question, why would Mosiah2 choose a Zarahemlaite and not a Nephite to lead an expedition to the Nephite land? Was it for reasons of unity? Was Mosiah2 thinking that if a native of Zarahemla led the expedition, there would be less chance of the expedition staying in the land of Nephi-Lehi and more chance of them returning to Zarahemla?

7:5 “forty days” The Mormon pioneers averaged about 2.25 miles per day. Ammon was also leading a large group and so we might be able to use the average distance covered by the pioneers to estimate the distance between Zarahemla and Nephi-Lehi. 40 days X 2.25 miles/day = 90 miles. I realize Ammon’s group “wandered forty days.” None the less, this gives us a possible idea of the how large of a geographical area the Book of Mormon covers.

Mosiah 7:7 – Mosiah 22:31-14 We do not return to the primary narrative of Mosiah2 and his people until Mosiah 22:13-14 and Mosiah 24:35. The question must be asked, who is keeping the record at this point and how did it end up in the Large Plates? Remember that in Omni 25, Amaleki gives the small plates to King Benjamin so that both the small and large plates are held by Benjamin and his descendants (i.e. King Mosiah2). Mosiah2 is not on this third expedition to find the Land of Nephi. So, someone is writing down the history that is taking place when Ammon and King Limhi meet. This record must have then been re-copied into the large plates. Or, maybe not.

7:15 It is odd that this expedition that has come from Zarahemla and is lead by a native of Zarahemla is being called a Nephite expedition. It adds to the claim that a Nephite was not necessarily a distinct race, but rather a cultural or religious identity. It also shows that despite having no contact with each other for at least a generation, both groups spoke the same language. This perhaps shows that the natives of Zarahemla now spoke the language of the Nephites.

7:17 Is this the temple that Nephi built?

7:18-32 Here we find Mormon quoting a primary source directly. That must mean there is something of importance being said. King Limhi’s speech follows more the way Nephi would speak in that he uses Hebrew scripture; King Benjamin did not. The fact that King Limhi uses the story of the Exodus leads one to believe that his people must of had a copy of the brass plates – at least in part. Or, he knows of the Exodus story because of Abinadi.

It must be remembered that by this time, the original Zeniff colony (of which King Limhi rules a part) has been divided into two groups. The larger population is led by King Limhi. The other group, the original Nephite church organized by King Noah’s former priest Alma1, was prospering in an independent settlement in the wilderness.

7:19 Most Bible scholars believe it was the smaller Reed Sea that was crossed, not the Red Sea. Are Mormons necessarily theologically tied to the idea that it was the Red Sea?

7:22 The origin of the agreement is found in Mosiah 19:15.

7:23 Barley is an anachronism. There is no evidence of Barley existing in Mesoamerica.

7:26 This is of course speaking of Abinadi whose story is told in Mosiah 11:20-17:20.

7:29-31 The sources of these quotes are unknown.

8:1 Who are “his people”? Lamanites? A combination of Lamanites and the left-behind Nephites? Just Nephites?

8:5 What is this obsession with keeping records?

8:6, 11 Why on Earth would King Limhi think that Ammon could translate?

8:9 What? More records?

8:10 Breast plates of metal is an anachronism.

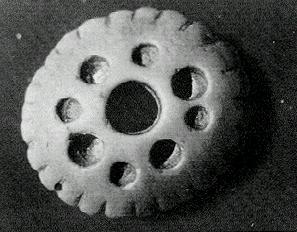

8:13 Dr. Michael D. Quinn says the following regarding the word “seer”:

“…the word ‘seer’ had particular significance within the magic world view. In his System of Magic; or, a History of the Black Art, Daniel Defoe wrote that in biblical times ‘they used to say when they wanted to enquire of God, that is to enquire about any thing difficult, come and let us go to the SEER, that is to the Magician, the wise Man, the Prophet, or what else you please call him.’ The best-known occult practitioner (magician) of the Elizabethan era was the Queen’s mathematician John Dee. He had a scryer (a person using a stone for divination) who was described in popular books as ‘Prophet or Seer to Dr. Dee.’ The earliest of these books recorded many spirit communications that Dee’s prophet-seer, Edward Kelley, revealed through his ‘Shew-stone‘ or ‘Holy-stone’. Francis Barrett wrote several pages about Dee and Kelley in his 1801 The Magus, the source for Joseph Smith’s Jupiter talisman (I have two copies of it, if anyone is interested in seeing it). As an 1839 book on witchcraft noted, Dee ‘firmly believed that by means of a small black stone with a shining surface, and cut in the form of a diamond, which he possessed, he could hold converse with the elementary spirits.’ Belief in elementary spirits would intersect with the subsequent visions of Joseph Smith as a divine seer.” (Dr. Michael D. Quinn, Early Mormonism and The Magic World View, 2nd edition, pg. 39,40)

Of course, Joseph Smith initially used one of his three “seer stones” for treasure digging, but later used one of them (probably the brown one) to translate the Book of Mormon and for receiving a few of the revelations in The Doctrine and Covenants.

8:14; Omni 20 The ability to interpret languages appears to be familial, as we know Mosiah1 did it with the large stone that was brought to him by the people of Zarahemla and now it seems King Mosiah2can do it too. Mosiah1of course translated the Jaredite record that was on a stone, not plates.

8:21 King Limhi is quoting Abinadi as found in Mosiah 17:17.

8:21-22 King Limhi is quoting his over-zealous grandfather’s record even before we read the record itself. Compare with Mosiah 9:3, 10.

The History of the People of Zeniff

Mosiah 9:1-21:27

This lengthy section is a historical digression that paraphrases the record read by Ammon in Mosiah 8:5. The account of Ammon and Limhi’s conversation about seers is resumed in Mosiah 21:28. It should be noted that only chapters 9 and 10 are related in the first-person narrative voice. Why would Mormon choose this way to tell the story?

Narratives that follow multiple characters often have to deal with the problem of how to clearly convey events that happened at about the same time in different locations. Here we see Mormon handling the problem through flashbacks. The history of the lost Nephite colony (the one Ammon finds and is ruled over by King Limhi) is told in a lengthy flash back that ends with a second account of the arrival of the searchers (Ammon), but will be told from the point of view of the colonists. At that point Mormon’s secondary narration returns not only to the main narrative sequence but even to the same conversation that had been interrupted thirteen chapters earlier.

Zeniff is an interesting character. He resists easy categorization. He is basically decent, yet everything he attempts turns out disastrously. His morally indeterminate status, along with the self-reflection that leads him to write candidly about his mistakes and weaknesses, makes him one of the most intriguing personalities in the Book of Mormon.

9:1 Apparently, Zeniff was not the leader of the first expedition from Zarahemla to the Land of Nephi. Here we see Zeniff’s talents in espionage are undermined by a virtue – compassion.

9:5 It appears that a Lamanite King (King Laman) is ruling over the Nephites that were left when King Mosiah1 left the Land of Lehi-Nephi. Too bad we don’t have the record of those Nephites that were left behind by King Mosiah1.

9:4 Zeniff manages to combine time-honored scriptural themes with his own unique sensibilities. “Wilderness” is a reference back to Lehi.

9:5 The use of the word“again” seems to indicate that during the first unsuccessful attempt at claiming the land of Nephi, Zeniff had spoken with the Lamanites prior to the in-fighting breaking out.

9:9 This is an odd verse because we get the barley anachronism again, but then we get two types of food (presumably grains) that we know nothing about – neas and sheum.

First war with the Lamanites (Mosiah 9:10-10:5)

9:11 Why would King Laman begin “to grow uneasy”? In twelve years, there is no way that Zeniff’s people could have grown large enough to be a threat to the Lamanites. Could Zeniff’s people possibly have joined with the other Nephites that were left behind by Mosiah1?

9:18 “And God did hear our cries and did answer our prayers.” Compare that with 2 Nephi 4:23-24; Jacob 7:22. It appears that Zeniff is reliving sacred history.

9:19 Zeniff buried the dead Lamanites. This might show his concern for his enemies as individuals.

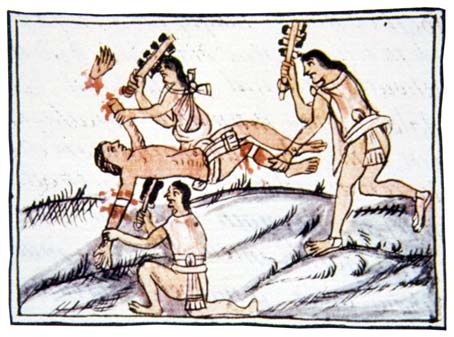

Second war with the Lamanites (Mosiah 10:6-22)

10:8 compare with 9:14 Lamanites are attacking from different sides.

10:10 Zeniff starts talking about the war and then stops. He doesn’t resume the details again until vs. 20 . This is a literary device that is known as suspension. Doing so allows the author to slip in something of importance while he has the readers at the edge of their seats. This is what Zeniff does. He explains the war from the Lamanite perspective!

10:12-18 Here we get further possible evidence that Lamanite was not so much a different race, but a different identity based upon beliefs. Zeniff’s narration is a little difficult to follow because he goes back and forth between what Lamanites believed happened and what Nephites believed happened in the foundational myths of their cultures.

10:19 This makes it sound like Zeniff’s digression from the narrative of the war was actually part of Zeniff’s exhortation to his men before going into battle.

10:20 compare with 9:19 Zeniff, after the second war, does not count the number of dead Lamanites. Does this perhaps indicate weariness on Zeniff’s part and dwindling idealism?

At this point it is reasonable to ask why Mormon chose to insert Zeniff’s memoir as an intact document? Was Mormon impressed by Zeniff’s example of faith dispite unexptected hardships, his devotion to his people, and his compassion for his enemies? Mormon undoubtedly identified with Zeniff’s predicament of trying to protect his outnumbered people from imminent destruction by the Lamanites, and Mormon could have wondered about the wisdom of the treaty he himself had negotiated – the only other treaty, besides Zeniff’s, mentioned in The Book of Mormon (Mormon 2:28; Mosiah 7:21; 9:2). Most likely Mormon slowed down and particularized his narrative at Zeniff’s founding of a colony because it was a pivotal moment in Nephite history. Although the colony eventually failed, Mormon knew that this settlement was the origin of both the Nephite Christian church and a line of prophets who would dominate the years leading up to the coming of Christ. These leaders include the two Almas, the two Helamans, and the two later Nephis.

11:1 Could Zeniff’s anxiety to see good in everyone and his faulty assessments of crucial situations, perhaps even as a father, have led to him being excessively lenient and long-suffering with his son Noah?

11:3-8 What is the precise identification of a ziff? It is uncertain. There is a related Hebrew word meaning “shining” and “to overlay or plate with metal.” These are some odd verses as many of the metals recorded here did not exist in Mesoamerica, but then we get this unknown “ziff”.

11:15 There is no archeological evidence of grapes or wine in Mesoamerica. Although they made an alcohol out of honey.

11:21 This prophecy is fulfilled in Mosiah 19:13-15, 25-28. Once again we get Mormon quoting a primary text.

2.25 miles/day? How could that be? The distance from Winter Quarters (Omaha Nebraska) to the Salt Lake Valley is roughly 1000 miles. This would take about 444 days at 2.25 mpd. Journal records for some of the first emigrants place the time of travel at about 122 days. This averages out to about 8.2 mpd. At that rate Ammon’s group could have traveled more like 328 miles in 40 days.

Jeff,

You have a good point. Here is where I got my information:

“Finally, by June 13, 1846, the first group of Mormons reached the Missouri River at Council Bluffs, Iowa. It had taken 120 days to cross 265 miles for an average of 2.25 miles a day. Some of these Mormons stayed in Council Bluffs, which was renamed Kanesville, while others crossed the Missouri and established Winter Quarters in present-day Omaha.” http://mojavedesert.net/mormon-pioneers/

I found the same numbers on other government web-sites as well. I googled “average distance traveled by Mormon pioneers”.

Here is what a different web-sight said that gave a number bigger than both of ours:

“Handcart company captains were men with leadership and trail experience. Each company included a few ox-drawn commissary and baggage wagons, at least one per twenty carts. Wagons or carts carried large public tents, one for every twenty people. A “Captain of Hundred” had charge of five tent groups. Five companies in 1856 and two in 1857 outfitted in Iowa City and needed a month to move 275 miles on existing roads over rolling prairie to Florence, averaging eight to nine miles per day. Passing through partly settled areas, they obtained some supplies along the way. After resting at Florence, these seven companies followed the Mormon Trail to Salt Lake City; on this stretch the first three companies spent an average of 65 days, covering 15.7 miles per day. Later companies leaving Florence needed an average of 84 days. By comparison, LDS wagon trains from Florence in 1861 needed 73 days to make the journey http://historytogo.utah.gov/utah_chapters/pioneers_and_cowboys/handcartcompanies.html

I am trying to make an argument for a “limited geography model” for the Book of Mormon. I think I have to build up a better argument.

mike

Another point to consider is that this group consisted of 16 strong men. They didn’t have any women or children with them and likely took just the bare essentials which would have allowed them to travel faster and further. But they weren’t traveling with a purpose, they were wandering. Which means they wouldn’t have been on a bee-line trail between the civilizations. Having said that, even if they traveled 400 miles, it still supports a more limited geography theory. It’s too far a stretch to claim that they truly populated all of North and Central America, from Panama up to New York. Were that the case we would go from a distance of hundreds of miles to thousands. It would take them years to cover that distance.

I apologize for shifting the subject: this post (and link: http://www.orbis-quintus.net/?p=3136) has nothing to do with the above topic. However, I think the link is interesting because it contains information about a people in Siberia who speak a language called Ket. This particular language is not connected linguistically to any other language in the surrounding region, but it has been shown to be related to the Na-Dene language family here in the Americas, therefore adding further evidence that Native American peoples most likely migrated– during and perhaps shortly after the last ice age– from eastern Asia to the Americas via the Bering Strait land bridge. Thus the origin of the present-day Native American peoples. Here is a related article http://www.scrippsnews.com/node/31329

Brent,

Super interesting. How did you happen upon this information? I wonder if a lingquist can decipher which language existed first? Did the Na-Dene come from the Ket, or vis-versa? I also wonder if there is any archeological evidence for people coming to the Americas from Asia and then crossing back over. I also would be interested in looking at DNA evidence that might tell us who descended from whom?

I came upon this story quite by accident in that I subscribe to a “Word-a -Day” vocabulary email and the story was located on the word-a-day’s web page. I have no answers to your questions regarding the linguistic ties between Ket and Na-Dene. I suppose linguistic migrations could have occurred in either direction,originally, or back and forth in both directions over time. Either way, the discovery seems to tie the two language groups together–even over a distance of thousands of miles.

I would assume that if or when physical migrations occurred between Asia and the Americas during the most recent ice age ( ten to 100,000 years ago), scant archaeological evidence would remain since the geographical makeup (ice sheets and glaciers) of Asia and the Americas would have been much different then. But then I’m neither an archaeologist, a climatologist, nor a geologist.

Dr. Michael Coe has written two excellent books on Mesoamaerica that I highly recommend for the mere fact that he does go into some detail about the archeological findings that appear shortly after the post-ice age migrations.

They are tilted, “Mexico” and “The Maya”

Thanks, I’ll check them out.