MOSIAH 1-3 “Eternally Indebted to Your Heavenly Father”

The above picture is the Wilford Wood fragments as observed on 30 September 1991, at the beginning of the conservation of the fragments. At the time no one knew what these fragments contained, but it turned out that a large portion of them were from the original manuscript of the Book of Mormon.

Beginning with The Words of Mormon, we are introduced to the second major narrator/historian of the Book of Mormon – Mormon himself. Since he is writing almost a thousand years after some of the events and re-recording what has taken place, we would expect his interpretation of events to be different than Nephi’s.

Grant Hardy notes:

“With that in mind, we have to constantly ask, why would Mormon include that? What might he have omitted? Is there any significance in the way he arranges events or tells particular stories? And who is Mormon anyway? After all, it is Mormon’s mind that will dominate the majority of the rest of the text.

“We come to know Mormon only gradually. He interjects his commentary or interpretation every so often. But it is not until the end of the text that we really get to know who Mormon really is. Mormon does not spend nearly as much time on his own life as he does on earlier prophets. His autobiography consists of just seven chapters. Mormon’s narrative style is distinct from Nephi’s. Stories and sermons are set within a thick historical framework and strict chronology. He offers very little scriptural exegesis (unlike Nephi). He seems to have little interest in House of Israel connections or messiah theology. The word messiah occurs 23 times in Nephi’s writings but only twice in Mormon’s (and never Moroni’s).

“Mormon is more attuned to narrative theology, that is , in showing how theological points are manifest or illustrated in particular events, and his fascination with prophecy is not so much reading himself into past revelations as using prophecies and their fulfillments to persuade his readers that God is directing history.

“The most striking difference between Nephi and Mormon is how much Mormon sees himself as a historian, with a responsibility to tell the story of his civilization comprehensively and accurately. It may have been that Nephi’s first version of his life story was equally concerned with the details of political and social change, but what we see in First and Second Nephi is as much meditation as memoir.

“Mormon believes that history, fairly and objectively written, will provide an adequate demonstration of God’s providence and design. Yet that does not stop him from adding specific moral commentary or shaping narrative into aesthetically pleasing patterns when the facts themselves do not quite covey his points. Nephi and Mormon, by contrast, give less weight to history than they do to visions of the distant future (in the case of the former) or the witness of the Spirit (in the latter).

“Mormon’s character is most clearly revealed as he tries to negotiate the divergent demands of being an accurate record keeper, a literary artist, and a moral guide. Having seen the destruction of the Nephites, Mormon knows that the primary readership for his abridged version of Nephite history would consist of Gentiles and descendants of the Lamanites in the latter days. This is in contrast to Nephi who is not quite sure whom he is addressing until the last chapter of Second Nephi, which might be surprising if one considers Joseph Smith Jr. the author of the Book of Mormon. Since Smith dictated the little book of Mormon (the book right before Ether) before 1 and 2 Nephi, the lost awareness of an audience would indicate strongly imagined narrators.” (Grant Hardy, Understanding The Book of Mormon, A Reader’s Guide; pgs 91-97)

Manuscript evidence suggests that the first two chapters of the Book of Mosiah were among the 116 pages lost by Martin Harris and that what is currently Mosiah chapter 1 was originally the third chapter in the book. This is perhaps why there is no summary headnote at the beginning of Mosiah.

Mosiah 1:2, 4 “taught in all the language of his fathers” What was the language? Hebrew? Aramaic? Here it seems to allude to some form of Egyptian. Were the Plates of Brass written in “reformed Egyptian”? And if so, did prophet/historians of the Book of Mormon use the Plates of Brass as a template for their history?

Mosiah 1:5 “traditions of their fathers” Belief in the correct traditions of the Nephites seems to have been the most important criteria in deciding who was or was not a Nephite. Apparently this acceptance of tradition was of more significance than actual lineage (Alma 3:11).

Mosiah 1:8 “and many more things did King Benjamin teach his sons, which are not written in this book” This shows Mormon is a deliberate, conscientious editor.

Mosiah 1:18 “to go up to the temple” This is a different temple than the one mentioned in 2 Nephi 5:16 . The first being built in the Land of Nephi. The one spoken of in the Book of Mosiah is in the land of Zarahemla.

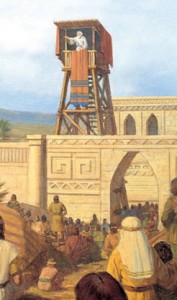

Mosiah 2:7 “he caused a tower to be erected” Does archeology give us any concept of what the tower might have looked like? In the Valley of Guatemala, there is a sprawling ancient city called Kaminaljuyu (“hills of the dead”). Here we find

One of the Earthen Mounds/Pyramids at Tres Zapotes, Mexico (Olmec). Probably more representative of Benjamin’s tower

enormous mounds found to date in part from B.C. times; although its most important remains are dated more towards the end of Book of Mormon times. Could the tower have been more like an earthen hill?

Mosiah 2:9-14 Here we get Mormon’s first insertion of a primary source into his narrative. What was Mormon’s purpose in doing so? Mormon’s insertion of the speech, verbatim, is most likely because of its significance as a founding, or even canonical document.

Why does King Benjamin recount his achievements? One possibility is that he was comparing himself to other kings that the people of Zarahemla knew of. This would not include Zarahemla, as he is never called a king in the Book of Mormon. Could Benjamin have been comparing himself to other kings of Mesoamerican city-states?

Is King Benjamin possibly trying to unite the combined peoples of the Nephites and Mulekites? Perhaps it is an attempt to unify his people along religious lines at a time when political tensions would have been high. In the peveious generataion, Benjamin’s father, King Mosiah, had led a group of Nephites to the land of Zarahemla. It has been suggested that there were Mulekites who still resented their loss of status and a transfer of power; endeavoring to keep it firmly in Nephite hands would have been a delicate political maneuver. John Tvedtness proposses that the “king-men” that we read of later in Alma 15, may have been disgruntled Mulekite scions (descendants) ( John Tvedtness, Warfare in the Book of Mormon; 298-299).

Mosiah 2:7 What language would King Benjamin have used when speaking? Remember that the majority of his congregation were the people of Zarahemla, not Nephi. Furthermore their language was corrupted and “the people of Mosiah, could [not] understand them” (Omni 18). What kind of tensions, if any, might this cause for Benjamin’s people?

Mosiah 2:10,11 “I of myself am [not] more than a mortal man. But I am like as yourselves” Understanding Mesoamerican culture helps us to put these verses into a context. The kings with which the people would have been very familiar would have been viewed as divine kings. Maya kings were considered to be divine. Here King Benjamin might be responding to the concept of divine kingship. He is reinforcing his humanity to his subjects.

Mosiah 2:38; 3:27; Mormon 9:5 “unquenchable fire” In Mormon 9:5 Moroni seems to be referring back to King Benjamin’s speech.

Mosiah 2:36, 37; Alma 34:35-36 “unholy temples” Compare Amulek’s warning to King Benjamin’s speech. This either shows the importance of Benjamin’s speech to later Nephites/Mulekites or the verbal parallels might be best explained as due to the common language and phrasing of Joseph Smith (either as translator or author).

Mosiah 3:3-10 Here we get one of the clearest prophesies of the Messiah.

Mosiah 3:11, 3 Nephi 6:18 “who have ignorantly sinned” In 3 Nephi 6:18 Mormon is relying upon the readers recalling the words of the angel that King Benjamin reported in his speech. We may wonder whether Mormon (or Joseph Smith) could have reasonably expected readers to notice this verbal parallel, but these are the only two instances of the phrase “ignorantly sin(ned)” in the entire Book of Mormon, so it seems like a conscious allusion. The impression it leaves is of Mormon as a careful editor, in full control of his sources, who is able to make sweeping connections over hundreds of years.

Thanks. Very insightful and thought provoking.

Hey Chris. Good to hear from you. Thanks for swinging by and giving us a peep. I miss your Gospel Doctrine lessons.

Mike

With respect to the tower mentioned in chapter 2 verse 7, we can’t immediately discredit the use of a wooden tower as depicted in the painting due to archaeological challenges. A wood structure rots and decays, often leaving no evidence of it’s existence. Stone on the other hand can survive through the centuries. The lack of wood structures doesn’t prove they didn’t use them, it merely doesn’t prove that they did use them. Even many of the stone structures remaining in the Mayan ruins have evidence of wood that has long since disintegrated. It’s not really that important, but these were just a few of my thoughts about the tower. I can envision a wooden structure being built on top of the earthen mounds that you mentioned.

I like the idea of Mormon including King Benjamin’s speech verbatim for a possible canonical document. This chapter is one of the greatest chapters in scripture that helps us to understand our relationship with other human beings. I love how clearly he helps us to see every human being as our brother and sister, and most importantly as our equal.

Momon tells us the people pitched their tents with the opening toward the temple so they could hear the words spoken by the king. I don’t know how the temple was constructed, but thought perhaps a raised structure was added to the outside of the temple. If the temple had an outter wall, it seems a platform could have been added to what already existed to easily create a high perch.