Black Pete and Early Mormonism

by

Mark Staker

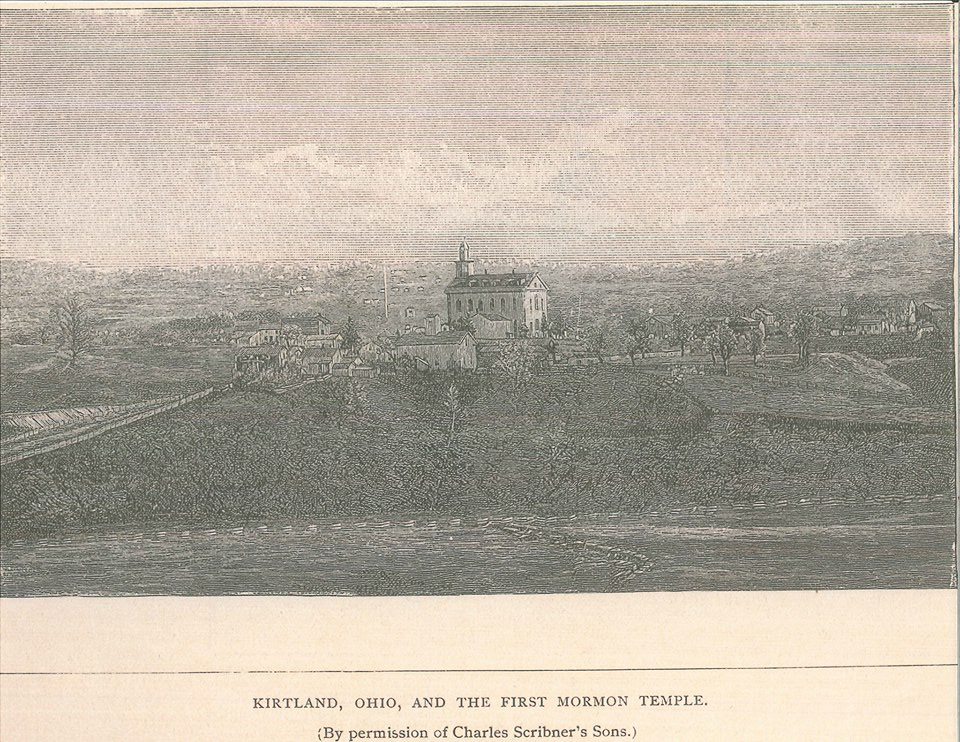

When Joseph Smith sent four missionaries to Missouri with copies of the newly printed Book of Mormon in October 1830, those missionaries went through Kirtland, Ohio. In Kirtland they found an African-American member of Sidney Rigdon’s reformed Baptist congregation who played a prominent role in the communal “Family” Rigdon’s followers had organized there. This man had been born into slavery as Peter Kerr, owned by John Kerr, a local iron worker in Fallowfield, Pennsylvania. But after Pennsylvania’s slaves gained their freedom, Peter moved to Ohio where he dropped his slave owner’s name and was simply known to his friends as Black Pete. Black Pete’s mother, Kino, had a Mandinka name and had likely shared her Muslim West African culture and heritage with her son as he grew up. Slave laws prohibited Black Pete from getting a formal education, therefore he was illiterate. Despite his lack of formal education, Black Pete had become influential in Rigdon’s reformed Baptist communal organization in northeastern Kirtland. He sometimes stayed at the home of N. K. and Ann Whitney, a local business family also connected to Rigdon’s reformed Baptist congregation.

When the missionaries arrived in Kirtland they baptized most of the members of the communal “Family” organization, including the Whitneys and Black Pete. The missionaries continued on to Missouri leaving few if any copies of the Book of Mormon behind and little instruction for the new members. As a result, the recent converts looked for leadership and direction from within their group. Observers claimed that Black Pete and his companions sought to act “as the Indians did when they were carried by the spirit.” This was done as they sought to understand the people of the Book of Mormon and imitate the lives of figures in that book.

Black Pete became “a chief man” and “a revelator” among them. Although it is not known if he was ordained to the priesthood, he likely was since he and some of his associates believed they received commissions to preach the gospel during ecstatic religious experiences and went about the community preaching and baptizing. This group began to practice speaking in tongues, which some outsiders called “talking Injun.” This was likely a reflection of their attempt to apply the Book of Mormon as they understood it. They also developed other ecstatic religious expressions that were common within the slave religious tradition familiar to Black Pete and his mother Kino.

Outsiders who observed these events often wrote of Black Pete with derision and ridicule. Because these non-Mormons sought to use his race to attack his religion in general, their slanted view makes it difficult today to discern all of his contributions to the community. At the same time, members that knew him failed to mention Black Pete at all. This suggests he may have left the Mormon community and separated himself from them. We don’t know. When Joseph Smith arrived in Kirtland, he received additional revelations that helped provide direction to the new members in the area and corrected some of the things they had been doing. Although he met Black Pete, and apparently tried to receive a revelation on Black Pete’s behalf, the historical record suddenly falls silent in relation to this former slave. Black Pete does not appear in census records, or other primary sources in the area, and he may have died or moved away. His brief involvement with Mormonism, however, left a lasting legacy. Black Pete may well have been the first African American member of the Church, as well as the first member who came from a Muslim heritage. He was clearly the first African American to contribute in a substantive way to the development of Mormonism.

For more information on Black Pete in historical context, see Mark L. Staker, Hearken, O Ye People: The Historical Setting of Joseph Smith’s Ohio Revelations (Salt Lake City: Greg Kofford Books, 2009).

That is cool. I am going to order your book. Thanks for sharing this post and bringing your book to my attention. Can’t wait.

Mark, this is awesome information. I’ve read your book, but didn’t know you had found out Pete’s last name. Where did you find that?

Rick B., you ask a great question. I think I actually address the issue in greater detail in the book than in this short piece, but I’ve never tried to explain his name thoroughly. The name of a slave during that period is a complex issue because most slaves chose names for themselves that differed from those given by their owners. This appears to be the case for Black Pete. His owners, John and Rachel Kerr, initially recorded his name as Peter when the manumission laws required them to register all their “property,” and they also listed his mother’s African name at the same time, which I suspect was not the name they used for her. Slaves were typically known by their owner’s last names and so Black Pete’s last name would have been Kerr. John Kerr described him as “my negro man Jack or John or sometimes known by the name of Pete” in his will. This suggests he was known as Jack Kerr while still a slave. (Slaves were almost never addressed formally and so he would not have been called John, just like he was Pete and not Peter.) Because ownership was transferred in his owner’s will, Pete was forced to remain in slavery longer than the manumission laws would typically have allowed. I suspect there was no love lost between Black Pete and the Kerr family, and so when he was finally able to get to Ohio and become truly “free at last” it was natural that he did not want to use his owner’s last name. It was also natural that he would choose to use Peter, the name his mother (I believe) gave him rather than John (Jack), the name his owners used. His friends and associates in Ohio all refer to him as Black Pete which suggests that was his preferred name, as Jack Kerr was quickly abandoned. I served my mission in Holland where Black Pete is the name of the sidekick of Sinter Klaas, and I don’t particularly consider it a complementary name. But in this instance I chose to use that name for this early African American convert to Mormonism because it was his preferred name (for the reasons I’ve mentioned). His original owners, the Kerr family, and his later owners, the Carrell family, all end up in Ohio and family members are found in a number of settlements in northeastern Ohio. I suspect there may be records of Black Pete using one of their names as his last name. But I’ve never been able to find them. If someone can find those additional records, it will shed more light on Black Pete and his contributions to early Mormonism and will be a real contribution to history. I hope someone will take on the challenge.

Mark

What a fascinating post! I had never heard of him before today.