AUTHORING THE OLD TESTAMENT: GENISIS-DEUTERONOMY – A BOOK REVIEW

by Michael Barker

I’m not sure when I first learned of the documentary hypothesis, but I do remember when I first heard that Dr. David Bokovoy was working on a book that would introduce the documentary hypothesis to an LDS audience. It was during a Mormon Matters podcast episode in October of 2013. I was immediately fascinated and anxious to get my hands on a copy. For those that have never heard of the documentary hypothesis, the hypothesis holds that the Bible comes from the writings of different scribal schools. Eventually all these documents were weaved together, by an unknown redactor, into a what we now have.

I had many questions regarding the hypotheses as it presents some unique problems for a traditional-believing Mormon. A few of my questions were:

-

What does this say regarding the Book of Abraham?

- What does this say regarding the Book of Moses?

- What does this say regarding Joseph Smith’s claim to be a translator and restorer of ancient scripture?

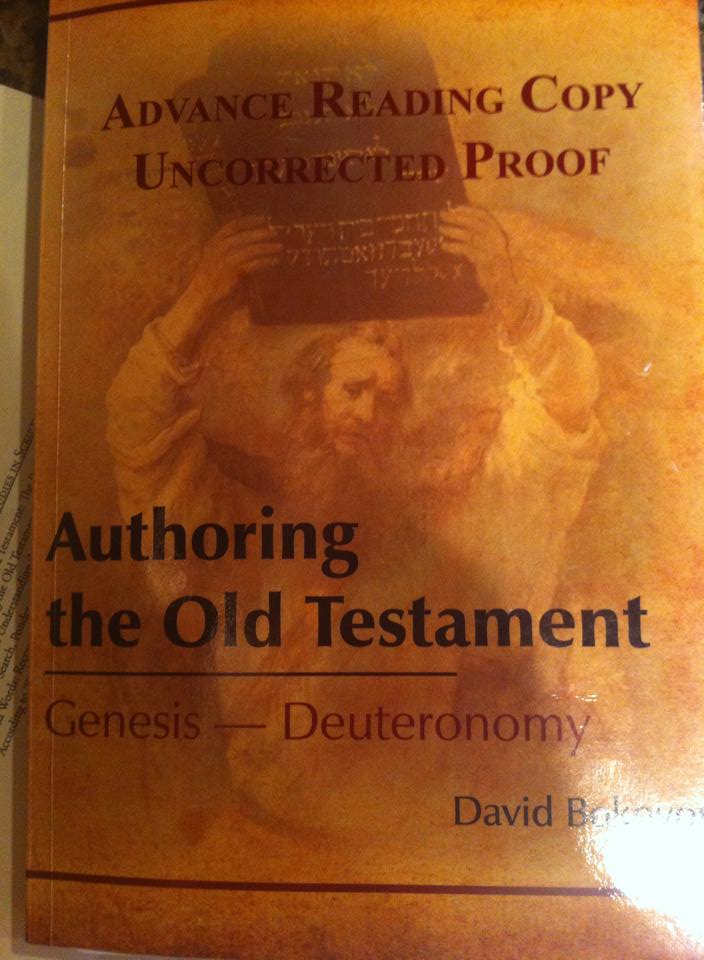

I was very excited when Kofford Books sent me an advance reading copy of Bokovoy’s book. I had listened to him on enough podcasts to safely assume that his approach to teaching this information would most likely be easily understood. So, enough of my dribble. To quote Nacho Libre, “Let’s get down to the nitty gritty!”

As you already ascertained, I am not a scholar. I am a run of the mill Mormon and that’s okay. This book was written for people like me. Up to now, the book reviews I have read of Bokovoy’s, Authoring the Old Testament, have been by those who are already well versed regarding the ins and outs of the documentary hypothesis. So, I hope this review will be more for the average Mormon reader.

In his introduction, Bokovoy sets out what he hopes readers will come away with:

“It is my sincere hope that this study will help confirm that within Mormonism, spirituality and critical thinking are not only not mutually exclusive paradigm, they are a united undertaking” (Bokovoy, pg X).

CHAPTER ONE – WHAT DOES IT MEAN TO READ THE BIBLE CRITICALLY?

Chapter one introduces the audience to the idea of reading the Bible critically. Bokovoy does this by inviting the reader to take a closer look at Genesis, chapters one and two. As he points out, there are two different creation narratives here. By using these two narratives, he shows how the two chapters provide a different view of God and of creation. He points out that Joseph Smith was a critical reader of the Bible. That is, he noticed the inconsistencies within the text. Joseph’s approach to these inconsistencies, however, was radically different than what prior interpreters had done:

“…when biblical texts like Genesis 1 and 2 appeared to contradict each other, qualified professional interpreters (such as scribes, rabbis, or priests) would reinterpret the plain meaning of words for their respective communities in a way that made the Bible conform with both itself and the interpreter’s particular religious preference. The Prophet Joseph Smith did not accept this type of interpretive approach. Instead, Joseph turned to what he identified as revelation and scribal errors to explain what he perceived as problems in the text”(Bokovoy, pg. 5)

Bokovoy then moves on to talk about the view that Moses was the author of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible; this is a view that almost no scholar of the Hebrew Bible accepts. Bokovoy dismantles the idea of Mosaic authorship of the Pentateuch with precision. He does so by going through a long list of inconsistencies of which I was completely ignorant, such as differences in law collections. The interesting thing that was as he did this, he pointed out how the Book of Mormon’s view of Israelite worship was actually consistent with modern scholarship. That is, the Book of Mormon presents Lehi as offering sacrifice at places outside of Jerusalem, as opposed to central place of worship. Using a scholarly approach to the Bible also gives us a window into Joseph Smith’s mind as an interpreter and redactor of the Bible:

“Theological changes [in the Old Testament] underscore the fact that those persons most responsible for maintaining the orthography of the texts tampered with their wording so as to preserve the religious dignity of these documents according to contemporary theological tastes”(Bokovoy, pg 16, quoting Michael Fishbane).

At the end of chapter one, and the end of all the chapters, Bokovoy has a short conclusion. This is very helpful as it is sometimes hard to see the forest through the trees of scholarship. In just a few paragraphs, Bokovoy is able to concisely and easily condense a chapter’s worth of scholarship. In the last paragraph of chapter one’s conclusion, he states:

“When combined with the historical anachronisms (including Moses’ death) that appear throughout the Pentateuch, it seems likely that these books were written by various individual long after the Prophet Moses. If we are going to make sense of these issues, we must follow the lead of Joseph Smith and the earlier European rationalists who influenced his world-view and begin and intellectual journey that takes the contradictions between these texts seriously”(Bokovoy, pg. 16).

CHAPTER TWO – WHAT? DIFFERENT SOURCES FOR THE PENTATEUCH?

Chapter two starts off by giving a great definition of the term, Higher Criticism and the historical critical method. Bokovoy defines thee as such:

“[Higher Criticism] refers to an attempt to explain the types of inconsistencies in the Bible we have witnessed so far by identifying original independent textual sources. Higher Criticism is an important part of what scholars today refer to as the historical-critical method, which refers to an approach to biblical interpretation that seeks to read the texts ‘historically,’ meaning in accordance with its original historic setting, and ‘critically,’ meaning independent from any contemporary theological perspective or agenda. As an expression, ‘Historical Criticism’ is the label that we often use today for mainline biblical scholarship that has been done for roughly the past two centuries”(Bokovoy, pg. 17).

With this clear definition, Bokovoy then goes on to explain what it is, and gives two wonderful examples of how the Documentary Hypothesis works. The easiest example for an LDS audience to grasp uses the Book of Mormon as an analogy. The Book of Mormon claims to be an ancient text that was produced by different scribes – Lehi, Nephi, Mormon, etc. Mormon, the redactor of all these scribal records, edits or compiled all the different documentary accounts into a single narrative. “This is precisely what the evidence suggests happened in terms of the development of the Pentateuch. At some point in time, Israelite scribes produced separate versions of their history (many of which covered the same events), and these documentary sources were eventually brought together by an editor that scholars refer to as a redactor,” explains Bokovoy.

To further add clarification that there were different scribal schools that provided the narratives of the Pentateuch, Bokovoy does something quite interesting. He takes the three chapters of Genesis that deal with the Noahtic story and separates the different sources by using bold font. In so doing, he is able to clearly show where the different scribal schools influenced the text and it really engages the reader.

Bokovoy is clearly able to make strong arguments for the documentary hypothesis, not only based on the creation narratives and the Noahtic story. He actually provides four strong arguments for this hypothesis. They are the inconsistencies in:

-

The creation narrative

- the Noahtic narrative

- the Mosaic Laws

- the story of Joseph being sold into Egypt.

CHAPTER THREE – HOW DO WE IDENTIFY THE SOURCES?

From here, Bokovoy moves on to how scholars identify the different source. In his opening paragraph of chapter 3, Bokovoy points out some of the challenges that the Documentary Hypothesis presents when he states, “It is much easier to identify the separate sources than it is to actually use the documents to recreate a textual history.” I appreciated his candor and transparency in pointing out this short coming.

Bokovoy first tackles the Priestly Source (P) which he believes was written in response to the Babylonian destruction of the Jerusalem temple in 586 BC and the Judean exile. While taking us through some unique aspects of the P Source, he clarifies something for me which I have been confused about. What the heck do scholars mean when the speak of the “prehistory’? You’ll have to pick up the book to see what he says about that.

Next, he tackles the Holiness School (H). This one I was excited to read about, as I had not read about this before. As I was reading the difference between the P and the H Sources, I was very intrigued because four years ago, while studying the Hebrew Bible, I started to make note of how often the word holy was used. I must admit I became a little confused between the differences of the P and H Sources as they sounded very similar, but Bokovoy offers this clarification:

“The difference between the P and the H is subtle but can nevertheless by identified. The Priestly Torah focuses upon priestly ordinances designed to maintain holiness through ritual activity. In contrast, the Holiness School shows a greater concern with how holiness, as a state of being, relates to humans, places, objects, times, and ultimately God himself…holiness is achieved primarily through moral behavior rather than ritual” (Bokovoy, pg. 49).

Next, we move on to the Yawistic Source (J). Bokovoy situates the J Source sometime seventh century BC. This would place the final J Source right around the time of Nephi and Lehi. Some of the unique characteristics of the J Source are:

- Southern Kingdom (Judah) is prominent

- More interested in how things began

- Yahweh has court or assembly

- The God of the J Source is anthropomorphic

Regarding the latter, Bokovoy does a great job of distinguishing the J Source’s view of an anthropomorphic God and that of Mormonism’s anthropomorphic God.

The Elohist Source (E) was interesting to read about as I wanted to learn the distinguishing factors between it and the P source; they both sounded very similar to me. Bokovoy points out that, “E is the most challenging source to identify in the Pentateuch” (pg. 55). While reading, I came across a very confusing sentence that I could not understand no matter how much I read it:

“Some scholars have argued that the editor primarily chose to include portions of E in the creation of the Pentateuch when E featured stories that a parallel version did not exist J, such as the story of Abraham” (page 55).

E is very ethnocentric; much like the Book of Mormon. That is, “if a story is not specifically an ‘Israelite’ account, then it was simply not worth telling”(pg. 55). It is in this portion of the book that Bokovoy shows his talent of using comfortable parallels in the Mormon narrative to explain a complicated concept such as we find in footnote 25 of page 55. In so doing, he is able to bring down possible reactionary defenses that some LDS readers may have to the Documentary Hypothesis. Now some distinguishing factors of E:

- Focuses on the Northern Kingdom (J &P) focus on the Southern Kingdom

- Focuses on the prophetic leadership of four of Israel’s ancestors; Abraham, Jacob, Joseph, and Moses.

- God reveals His will by means of dreams or vision rather than direct appearances

- Frequent references to Angels. This puts Elohim at even a greater distance than what we find in P

- Probably written in the Northern Kingdom around the ninth century BC; making it older than J or P.

- In the E Source, God reveals His name (Jehovah) to Moses three chapters earlier than the P source. The fact that God reveals His name as Jehovah in two different places points to the idea that there are two sources in play.

Bokovoy then goes on to give a short and concise historical survey of Mormonism’s tradition of referring to God the Father as Elohim and Jehovah as His premortal son. At this point of the book, I would have enjoyed a deep dive into the names, Elohim and Jehovah. How are these two names different from eachother? When is Elohim plural vs. singular? When is El used as opposed to Elohim? What theological benefit do Mormons get from making such a hard-line distinction between Elohim and Jehovah?

Bokovoy then takes us on to the Deuteronomic Source (D). This souce also interested me a great deal as I had very little concept of how it came into play with the Pentateuch. Some distinguishing factors of the D Source that Bokoovy points out:

- Israel is holy because they are chosen by God. This as opposed to P (holy though ritual) and H (holy through obedience).

- Comes from an Israelite scribal school from the Northern Kingdom

- Lacks any formal references to the Southern Davidic dynasty

- Heavy emphasis on prophecy (see Deuteronomy 18:15-22)

- The Holy Mountain of God is Mt. Horeb (the north authors) as opposed to Mt. Sinai (southern authors).

- Deuteronomists started their Israelite history prior to the Northern Kindom’s fall to Assyria in 772 BC.

- Importance of central worship, ie the Jerusalem temple. Which is weird if you think about it because the Deuteronomists emphasize the Northern kingdom.

- Emphasis on the ONE. One God. One acceptable temple. One chosen people of God to serve as His one covenant people.

- The Shema is found in the D Source

- God is less corporal than even the P Source and provides the D Source’s justification for the prohibition against idolotry (see Deuteronomy 4:15-16)

- It is God’s name (not body) that dwells in the temple. This is in contrast to the P source where God’s glory (God’s kavod, which scholars typically see as physical/corporal (but less corporal still than J)) dwells in the temple (See Numbers 14:10)

I found the connections that Bokovoy made between Deuteronomist exiles to the Southern kingdom, Hezikiah’s and Josiah’s reforms super fascinating. Loved it.

Now, one thing that can easily be missed by the non-scholar, like myself, is the forest through the trees. I can get easily overwhelmed by the neat details, that I forget how different ideas compare to eachother. It appears that Bokovoy know this, as he provides a wonderful table on page seventy-one which provides a clear summary of distinguishing characteristics between the different sources.

CHAPTER FOUR – DATING THE SOURCES

Chapter four starts off by addressing the argument that the logic behind the Documentay Hypothesis is ciruclar. That is, it assumes what it is trying to prove. An expample woud be, “since J perfers to use the divine name, Jehova, source critics simply identify a literary section where Yaweh appears as J.” Bokovy counters this criticism by saying:

“The truth is however, that the identification of these unique sources constitutes a secondary, rather than a primary feature of the analysis”(pg. 73)

At this point, Bokovoy introduces the reader to the term, diachronic analysis, which is “the study of the manner in which language evolves over time”(pg. 77). This is an important concept, as much of the dating for the different sources has to do with how the Hebrew language changed over time. Bokovoy compares the differences in the Hebrew language by comparing how different modern English is to the English found in Beowulf. By separating the different Pentateuchal texts according to their narratives, a diachronic analysis can help determine the historical relationship of the sources to one another. Here, Bokovoy cites the work of scholar Richard Elliott Friedman to show us what a diachronic analysis can reveal:

-

The Hebrew of J and E comes from the earliest stage of biblical Hebrew

- The Hebrew of P comes from a later stage of language

- The Hebrew of the Deuteronomistic texts comes rom a still later stage of the language

- P comes from an earlier stage of Hebrew than the Hebrew of the Book of Ezekiel (which derives from the time of the Babylonian exile).

- All of these many sources come from a sstage of Hebrew knows as Classical or “Standard” Biblical Hebrew, which is earlier than the Hebrew of post-exilic, Persian period (known as Late Biblical Hebrew).

With all of this, there are still some things that still confuse me.

- What the heck is “Biblical Hebrew” exactly?

- Page seventy seven states, “…late historical books in the Old Testament, like Esther and portions of Daniel, were written in Aramaic instead of Hebrew.” Three pages later, Bokovoy states, “..the linguistic evidence behind the biblical sources show no signs whatsoever that the biblical sources could have been original written in a language other than Hebrew.” Huh?

CHAPTER 5 – MESOPOTAMIAN INFLUENCE

My immediate question is, “Why couldn’t the Hebrews have influenced the Mesopotamians instead of the other way around?” Well, it turns out that Bokovoy answers that question directly:

-

No historical reason to believe that the Mesopotamian scribes would have adopted Israelite sources.

- Israel and Judea were controlled by Mesopotamian empires throughout history

- Israelite scribes were trained in Akkadian (the language in which the Mesopotamian sources were written).

- The Bible adapts the Laws of Hammurabi and Vassal Treaties

- The Mesopotamian texts predate the period in which the biblical sources were written.

- Based upon the Bible’s own internal chronology, it is impossible for any of the Hebrew sources to have existed prior to the mid-second millennium BC, when the Hebrew nation originated through Abraham

- If Abraham somehow brought with him written sources from Ur that later scribes drew upon, those hypothetical sources would have been Mesopotamian.

Well, he answered that question soundly. Regarding number 6, I would have liked to seen an example of “internal chronology.”

From here, Bokovoy brings some fantastic insights to the Hebrew word tehom (deep) and the Akkadian word, Tiamat (the sea monster that the Babylonian God, Marduk, fights in the myth Enuma Elish). Also, Bokovoy’s insights regarding the divine council, the idea that Yahweh is working with pre-existent material with creation (not ex nihilo), and the way he ties it all into the Enuma Elish myth was super fantastic. Loved it, and I think that even the more traditional-believing Mormons would find these insights helpful.

One of the questions I use to have with the Adam and Eve story was, what is the purpose of the story? I mean, Adam and Eve could obviously make choices before eating the fruit; they are able to name animals before eating the fruit. They were obviously sentient beings. So what kind of knowledge does the fruit bring? Bokovoy makes a strong argument that it is sexual awareness. The J source uses eating as a euphemism. Bokovoy points out this isn’t the only part in the Bible where such a euphemism is used:

For the way of an adulteress:

she eats, and wipes her mouth

and says, “I have done nothing wrong” (Proverbs 30:20)

Is there something different about human’s sexual awareness? I mean cats and dogs copulate too. J does see human sexual behaviour as different. “For J, humans possessed an advanced knowledge of sex unlike the animals, but very much like the gods” (pg. 107).

Bokovoy then makes his way through the parallels seen in Genesis and the Sumerian King Lists, Mesopotamian flood myths, and the Tower of Babel, Covenant Codes of Hammurabi (the discussion of Apodictic and Casuistic Laws was fascinating), Deuteronomy as Assyrian Vassal Treaty, Sargon of Akkad and Moses.

There was one confusing part for me in the above listing. Regarding the Noahtic story, Bokovoy states:

“Humanity is evil, constantly seeking to usurp the boundary Yahweh sought to maintain between gods and humans. However, following the flood and sacrifice that ‘feeds’ Yahweh through smell, he changes in the course of the story. Yahweh comes to terms with humanity’s nature (see Genesis 8:21).

P shares the same Mesopotamian themes, however, it invokes them differently. In P, God created humans and commanded them to only eat plants (see Genesis 1:9). However, humanity proves unable to rule and have dominion as the ‘image’ of God; and the overpopulation and not enough food, the earth became filled with violence (Genesis 6:11). In P, God sends the flood to eradicate this problem. Without the sacrifice that we find in both J and Mesopotamian tradition, P’s resolution to the flood story simply involves God changing his stipulation that humans could not eat meat (Genesis 9:3)” (pg. 112).

How does allowing humans to eat meat take care of the problem? Is it that humans can now eat meat and so they don’t get so hungry and violent anymore?

Regarding the Assyrian Vassal treaty, Bokovoy makes a wonderful connection between it, covenantal devotion, and the Book of Mormon; you’ll have to read about it, sorry.

CHAPTER SIX – READING THE PENTATEUCH CRITICALLY AS A LATTER-DAY SAINT

In the opening paragraph to this chapter, Bokovoy gets right to the heart of the problem of Historical Criticism as it pertains to Mormonism. He provides a quick view into how he is going to resolve the problem:

“A critical analysis, however need not be interpreted as antithetical to religiosity. It only presents problems for certain religious paradigms that run against such an approach” (pg. 123)

As he negotiates through the problems that critical analysis can provide, Bokovoy uses the Prophet, Joseph Smith as our guide:

“The fact that Joseph Smith went to scholars to gain knowledge concerning the scriptures shows that he believed that revelation was no the only way to read scripture” (pg. 126)

Later Bokovoy provides another gym of a quote that could really put at ease those that are uncomfortable with some of the conclusions that the Documentary Hypothesis can make:

“The Christian world accepts the Bible as the word of God. Most have no idea of how it came to us. I have just completed reading a newly published book by a renowned scholar. It is apparent from information which he gives that the various books of the Bible were brought together in what appears to have been an unsystematic fashion. In some cases, the writings were not produced until long after the events they describe. One is led to ask, ‘Is the Bible true? Is it really the word of God?’ We reply it is , insofar as it is translated correctly. The hand of the Lord was in its making” (pg. 131, quoting Gordon B. Hinkley, “The Great Things Which God Has Revealed,” Ensign, May 2005, 81).

Isn’t’ that an amazing and confirming quote? I have to share one more wonderful quote before moving on to chapter 7:

“In a nutshell, here is my view of the Bible as a Jew: The bible is a sourcebook that I – within my community – make into a textbook. I do so by selecting, re-evaluating, and interpreting the texts that I call sacred” (pg. 132, quoting Marc Zvi Brettler, How to Read the Bible, 280).

CHAPTERS SEVEN THROUGH NINE – HIGHER CRITICISM AND THE BOOK OF MOSES, THE BOOK OF ABRAHAM AND THE BOOK OF MORMON

Beginning with chapter seven, Bokovoy begins to tackle some of the unique problems that the Documentary Hypothesis poses for scripture that is unique to the LDS tradition. These next chapters is where the gold is. I will honor Bokovoy’s request by not spilling the beans as far as his conclusions go:

“I recognize that some readers will no doubt feel tempted to start with the concluding chapters that focus on the implications of Higher Criticism for the Book of Moses, the Book of Abraham, and the Book of Mormon. I hope that my reader will avoid this temptation and instead choose to approach this book like he or she would a detective novel. I believe that it is essential that the reader first understand the ‘case’ before skipping ahead to learn the ending” (pg. xii, footnote 2).

I will say this, I appreciated Bokovoy’s candor in exploring the problems that our unique LDS scripture has with regards to the Documentary hypothesis. He brings up issues that I was aware of, some that I wasn’t aware of, and one in particular that I’ve seen as a problem, but have never seen addressed until reading this book. Bokovoy, to his credit, never ends these chapters on a sour note. He ends each chapter with some unique connections between these books and the ancient Near Eastern World, ways to nuance one’s approach to scripture, and then short summary conclusions. Each of these three chapters essentially follow as follows:

-

Problem

- Possible Solution

- Ancient Near Eastern connection

- Conclusion

Okay, I’ll give you a little pearl he provides just to tease you:

“Historicity is never the construct that defines scripture as scripture” (pg. 171).

MY CONCLUSIONS

I loved this book and you should buy it. Not super articulate, but it’s true. David Bokovoy has converted me to the ways of Higher Criticism.

Let me end with his closing thought in his concluding chapter:

“Historical Criticism allows Latter-day Saints to make informed judgments about the Bible’s current meaning and significance (or insignificance) in their lives. From this angle, Historical Criticism is a spiritual quest. It is a quest for truth”

Amen.

I love David Bokovoy’s stuff. When I go to Education Week at BYU, he’s the class that is a must attend. I hope they let him teach this year.

I don’t want to praise the man too much, but he’s one of only a handful of scholarly bright lights we have left in the Church. The rest of the Religion faculty at BYU are CES know-nothings that parrot the party line and have no scholarly background at all.

Thanks for the review. As I would read anything by Bokovoy, I’m looking forward to his book.

“The rest of the Religion faculty at BYU are CES know-nothings that parrot the party line and have no scholarly background at all.”

As one who has taken classes from and worked as a research and teaching assistant with a number of different religion professors at BYU, I can assure you that this egregious statement is categorically false. Believe what you want about religious education at BYU, but to assert that the faculty of the College of Religious Education are “CES know-nothings” with “no scholarly background at all” is as shockingly ignorant as it is bigoted. I dare you to check out the CVs of David Seely, Dana Pike, Thomas Wayment, Eric Huntsman, Richard Holzapfel, Robert Bennett, Alex Baugh, Lincoln Blumell, Mark Wright, Shon Hopkin, Jeffrey Chadwick, Matthew Grey, Brian Hauglid, Andrew Hedges, Paul Hoskisson, Michael McKay, Kerry Muhlestein, Andrew Skinner, and Dan Belnap, to name a few, and then assert that they’re “CES know-nothings” with “no scholarly background at all.”

Yes,a few of the names you mentioned are in the handful of scholars that I spoke of, but the vast majority are still know-nothings parroting the party line. Yes, most of the Religion department people have degrees, but they are degrees in education,and social sciences or what have you, but are not scholars in ancient history or religion. They are CES people….hello? No scholars allowed in that bunch. When the Education Week schedule comes out, look at the degrees of the people who are teaching! PhDs in education for crying out loud! Like I said…there are just a handful of people who are actual scholars and know anything.

“Yes, most of the Religion department people have degrees, but they are degrees in education,and social sciences or what have you”

And what’s wrong with that, exactly? People with PhDs in education or sociology can’t teach Church history or the scriptures?

You also do realize that one of the purposes of the Religious Education department is to train and prepare those poor “know-nothing” saps wanting to pursue a career in teaching with Seminaries and Institute, thus necessitating a need within the department for those with professional degrees in things like education, right?

“but are not scholars in ancient history or religion.”

Rubbish. In addition to the names that I provided above, which constitutes nearly a third of the faculty, I could also include Kent P. Jackson, Kerry Hull, Ray Huntington, Frank Judd, Jared Ludlow, Robert L. Millett, Roger P. Minert, D. Kelly Ogden, Camille Olson, Gaye Strathearn, Kip Sperry, Mauro Properzi, and Fred E. Woods as those with degrees in history & related fields (remember, the College of Religious Education also teaches 19th century Mormon history and modern Church history in addition to ancient scripture), or religious studies.

Oh, and by the way, this doesn’t include professors who teach in the History department or the Asian and Near Eastern Languages department that have also contributed to Mormon scriptural or historical studies, like Donald W. Parry, Stephen D. Ricks, Daniel C. Peterson, James A. Toronto, Ed Stratford, J. Spencer Fluhman, Glenn Cooper, Grant Underwood, or the soon-to-retire William J. Hamblin.

“They are CES people….hello? No scholars allowed in that bunch.”

Does that include “CES people” like Bokovoy himself? More to the point, you do realize how bigoted and pompous you come across saying stuff like that, right? I happen to know personally people who teach in the Seminaries and Institute system that are very sharp, scholarly, and qualified to teach religion.

“Like I said…there are just a handful of people who are actual scholars and know anything.”

As opposed to you yourself, right Bruce? I’m sure your own academic credentials in history, Mormon history, ancient studies, and/or religious studies are just as if not more impressive than any of those wannabe clowns I’ve listed above.

For the record, I usually don’t like doing this kind of thing, but when people say ignorant and disparaging things about the department at BYU that I’ve worked for and have come to love, as well as the wonderful, smart, and qualified faculty members of said department that I’ve gotten to know, I have to speak up and say something.

Bruce, although Stephen has responded above, I would like to add a few more details to what he has said. I enjoyed your kind remarks in your first comment above, excluding the middle paragraph. Let’s take a quick look at your statements that those in the Religious Education department are “know-nothings”:

Based on your criteria above, that a “true scholar” in religious education has to have credentials in the field of scholarship they are teaching, out of the 68 members of the faculty listed on the BYU Religious Education department’s website, 35 of these hold PhDs in their respective fields of scholarship. Of the rest of the members 31 hold their PhDs in Education, Psychology, Marriage and Family Studies, Sociology, Law, Instructional Technology, etc. There are 2 left that I can find no information on about their specific education. This means that just barely over half the professors in the Religious Studies department, according to your standards, are qualified to teach in their positions (51.47%), where a little less than half (45.59%) are not fit to be in their positions, and leaving the 2 that at the moment I am unsure about.

Although 45.59% is a large portion of the over all group, the majority of professors in the Religious Education department are fit for their jobs according to your standards. This does not include any investigation into how much these respective scholars are actively engaging with their respective fields, but it does highlight the fact that the majority of professors in the department have received their training at accredited universities in their fields. I think that at least this fact requires you to recant your above statements, as I assume Stephen (and those in the Religious Education department) would appreciate you doing.

I know where you are coming from in making your statements. I study under David Bokovoy at the University of Utah, and, as much as I enjoyed attending BYU in the Summer of 2012 as a visiting student, I am fully aware of the need to improve the level of rigor that is required in those classes. I can strongly state that David Seely’s class on the first half of the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament was rigorous; it was one of the hardest classes I took bother Spring and Summer terms (and I took an accelerated first year Hebrew course the Summer term). I think your statement is based on a number of assumptions and requirements that we both share that I think does not extend to the Religious Education department at BYU. I will explain.

You and I (I assume, correct me if I am wrong) expect any college education having to do with Biblical or religious studies in general to be top notch, up to date with all rigorous scholarly discussions of Biblical/religious studies and to impart this much needed information on to the students in the classroom. Whether or not the information is accepted is not important, as long as the students are aware of the problems and issues of religion in their education they will be stronger in the world and better off in many ways. In this light, the scholars that are given jobs in departments that teach biblical studies/religion should have PhDs in their respective field so that (1) they are aware of the problems and issues, and can impart that knowledge accordingly, and (2) have experienced writing on, presenting on, and debating with other scholars in the field so that they are not working with their ideas and impressions by themselves or simply those likeminded as they are. Here are a few reasons why I do not think this applies fairly to the Religious Education department at BYU:

(1) The credits earned in the Religious Education department are only worth 2 credits and do not transfer to most other institutions. Brigham Young University itself implicitly recognizes these courses as specific to the “religious education” (in Mormonism, specifically) of each of its students. These classes are not made to transfer; they are made specifically for the religious heritage of the university.

(2) The department itself is titled “Religious Education.” I would not expect to impose harsh strictures on a department that ops for “Religious Education” rather than a more appropriately academic title “Religious Studies.” This is not to say the Religious Education department is academic or not; rather it highlights the fact that academia is not their focus. There is of course the “Religious Studies Center,” but that is not the topic of our discussion.

(3) Is it really possible to impose the idea that someone in Education, Psychology, Family development, etc. cannot teach a religious education course due to the department they received their PhD in? I don’t know if this is an entirely fair requirement to impose on those in the department. Although I see much of the curriculum in the department, from what I have heard through discussion with those who take many of the courses, as a sort of glorified seminary or institute curriculum (although not those classes I took; they were different), I would not expect every professor to be taken from the academy. A quick overview of the courses taught in the Church History and Doctrine section of the department will show that the courses do not require this (see http://saas.byu.edu/catalog/2011-2012ucat/departments/RelC/RelCCourses.php).

As much as I agree with your desire to have a more rigorous approach across the board in the Religious Education department (and a more careful selection of some of the professors, i.e. Alonzo Gaskill and his PhD from a non-accredited Theological Seminary that requires no language skills at all of their PhD candidates), I think that the expectations that you and I have in this regard are not in line with the raison d’être and mission of the Religious Education department. We cannot expect others to fall in line with our expectations just because we have them; there have to be real and meaningful reasons for others to meet our expectations. In this case, our expectations may not meet the needs of the department. We should probably focus our attention on discussing the other departments Stephen notes above.

Bruce, I’ll also add the information here on all of the faculty in the Religious Education department for your browsing needs. If we expect others to be thorough and informed, we should probably require the same of ourselves if we are to be taken seriously. 🙂 The section titles should not be taken too seriously; they are simply based on your “criteria” for scholars to be fit for their field:

Scholars

Terry Ball – BYU Master Ancient Near Eastern Studies (1990), PhD in Archeobotany, emphasis in Ancient Near East (1992)

Alex Baugh – Master’s in History (1986), PhD American History (1996)

Dan Belnap – MA and PhD in Northwest Semitics, University of Chicago (2007?)

Richard Bennett – PhD U.S Intellectual History, Wayne State University

Lincoln Blumell – M. St. Jewish Studies at Oxford (Christ Church), PhD Religious Studies (Early Christianity) at University of Toronto

Jeffrey Chadwick – MA International and Area Studies (Near Eastern Studies), PhD Archaeology and Anthropology (Archaeology of the Land of Israel) at U of U

Rachel Cope – MA American History at BYU, PhD American History (American Religious History and American Women’s History) at Syracuse University

Richard Cowan – PhD American History at Stanford University (1961)

Amy Easton-Flake – MA English at BYU, MA Women’s Studies at Brandeis, PhD American Literature (19th century Women’s literature and narrative theory) at Brandeis

Matthew Grey – MA Archaeology and History of Antiquity at Andrews University (2005), M. St. Jewish Studies at University of Oxford (2006), PhD Archaeology and the History of Ancient Judaism at University of NC Chapel Hill (2011)

Brian Hauglid – MA and PhD Arabic and Islamic Studies at U of U (1991 and 1998)

J. B. Haws – PhD American History (20th Century LDS History) at U of U

Andrew Hedges – MA Near Eastern Studies at BYU, PhD American History at University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign

Richard Holzapfel – MA at Hebrew Union College, PhD at University of California, Irvine

Shon Hopkin – MA Near Eastern Studies (Hebrew Bible) at BYU, PhD Hebrew Studies (Medieval Hebrew, Arabic, and Spanish Literature) at University of Texas at Austin

Paul Hoskisson – MA BYU(?), PhD Ancient Near Eastern Studies at Brandeis

Kerry Hull – PhD Linguistics and Mayan Something(?) at University of Texas, Austin

Eric Huntsman – MA Ancient History at University of Pennsylvania (1992), PhD Ancient History at University of Pennsylvania (1997)

Kent Jackson – MA and PhD Near Eastern Studies at University of Michigan

Frank Judd – PhD New Testament at University of NC Chapel Hill

Jared Ludlow – MA Biblical Hebrew at University of California Berkeley, PhD Near Eastern Religions at UC-Berkeley and Graduate Theological Union

Michael Mackay – MA World History, Culture, and History of Science and Medicine at University of York (England), PhD Cultural Theory, History of Science and Medicine and Print Culture at University of York (England)

Robert Millet – MS Psychology, PhD Religious Studies at Florida State University

Roger Minert – MA German Literature Ohio State University, PhD German Language History and Seccond Language Acquisition at Ohio State University

Kerry Muhlestein – MA Ancient Near Eastern Studies at BYU, PhD Egyptology at UCLA

Kelly Ogden – M. Ed. International Education, MA Hebrew Language and Historical Geography of the Bible, PhD Middle East Studies

Camille Olson – MA Ancient Near Eastern Studies, PhD Sociology of the Middle East

Dana Pike – PhD Hebrew Bible and Ancient Near Eastern Studies at University of Pennsylvania (1990)

Mauro Properzi – MA Theological Studies at Harvard Divinity School, M. Phil. Psychology and Religion at Cambridge University (Peterhouse), PhD The Study of Religion (Mormon Studies)

David Seely – MA Classics at BYU, A. M. Ancient and Biblical Studies at University of Michigan (1985), PhD Ancient and Biblical Studies at University of Michigan (1990)

Andrew Skinner – MA Jewish Studies at Illiff School of Theology, Th. M. Biblical Hebrew at Harvard, PhD Near Eastern and European History at University of Denver

Gaye Strathearn – MA Near Eastern Studies, PhD New Testament at Claremont Graduate University

Thomas Wayment – PhD New Testament Studies at Claremont Graduate University

Fred Woods – MS International Relations at BYU, PhD Middle East Studies (Hebrew Bible) at U of U

Mark Wright – MA Anthropology at UC Riverside (2004), PhD Anthropology (Mesoamerican Archaeology) at UC Riverside (2011)

“Non-Scholars”

Kenneth Alford – Master Computer Science (1988), PhD Computer Science (2000)

David Boone – Master’s American Western History (LDS Pioneer History) at BYU, PhD Educational Leadership (LDS Academics and Church Education) at BYU.

Kent Brooks – Master’s Counseling, PhD Family Studies.

Guy Dorius – MA Education Administration, PhD Family Studies at BYU

Scott Esplin – M Ed. and PhD in Educational Leadership and Foundations at BYU

Brad Farnsworth – Master of Accountancy at BYU

Robert Freeman – BA (?), Law Degree at Western State University

Alonzo Gaskill – PhD Biblical Studies from non-accredited Trinity College of the Bible and Theological Seminary (no language classes or requirements for PhD)

Michael Goodman – MA Information Technology, PhD Marriage, Family, and Human Development

Tyler Griffin – MA and PhD in Instructional Technology

John Hilton, III – MA Education at Harvard, PhD Education at BYU

Stanley Johnson – PhD Education at BYU

Daniel Judd – MS Family Science at BYU, PhD Counseling Psychology at BYU

John Livingstone – MA Education, Guidance, and Counseling at University of Regina, PhD Education, Counseling, and Personal Services BYU

Craig Manscill – MA Sociology at BYU, PhD Sociology at BYU

W. Jeffrey Marsh – PhD Educational Leadership at BYU

Byron Merrill – J.D. at University of California

Barbara Morgan – MA Educational Leadership, PhD Instructional Psychology

Lloyd Newell – MA Communications at BYU, PhD Marriage, Family, and Human Development at BYU

Mark Ogletree – Master’s Mental Health Counseling and Educational Psychology, PhD Family and Human Development at Utah State University

Craig Ostler – PhD Family Studies at BYU

Todd Parker – M. Ed. and Ed. D. in Educational Psychology at BYU

Jennifer Platt – PhD Lifespan Developmental Psychology at Arizona State University

Matthew Richardson – M. Ed. Educational Leadership and Curriculum at BYU, PhD Educational Leadership at BYU

Kip Sperry – Graduate Degree(?) Library and Information Science

Anthony Sweat – M. Ed. (2005), PhD Curriculum and Instruction (2011) at Utah State University

Charles Swift – PhD Educational Leadership and Foundations at BYU

Brent Top – Master’s Instructional Media, PhD Instructional Science and Technology

David Whitchurch – M. Ed., PhD Educational Psychology at BYU

Keith Wilson – PhD Educational Administration

Mary-Jane Woodger – M. Ed. Utah State University (1997), Ed. D. Educational Leadership at BYU

Not Sure

Ray Huntington – PhD in Sociology: Middle East at Somewhere(?) (cannot find anything about where he received this)

Dennis Largey – No information on past education

Does no one here understand what it is to parrot the party line? You could have all the degrees in the world, but what good does all that knowledge do you if you just parrot what the CES dept allows you to teach?

Ask each and everyone of those people on your list if they live in FEAR of stepping over the line and actually teaching things differently than what is allowed. They will be the first to say independent thinking in NOT allowed at BYU much less teaching that independent thinking. People who don’t follow the party line get fired.

And yes, and let me be blunt so you don’t misunderstand…education degrees are crap when it comes to teaching ancient religious history.

Bruce,

I think you completely misunderstood what I said above. Did you read everything? I said that you and I share the same assumptions, and our conclusions are the same. I understand what you are saying, except maybe with David Seely. I was a visiting student (I am a student at the University of Utah studying Hebrew underneath David Bokovoy, like I mentioned above) at BYU in the summer of 2012 and Seely was very courteous and open to my comments/questions as we moved along through the Hebrew Bible/Old Testament. Not only did I bring a lot of alternative approaches to the Hebrew Bible that do not usually bring up in Sunday School or Seminary/Institute, I learned a whole lot from him in that same regard. Does David Seely fear stepping over the line in his classes? You would have to ask him, but I think he would say no. Again, he is only one of sixty-eight professors on staff.

Also, your last line contradicts what you earlier stated, and I would have to disagree with it anyway from an academic perspective. Your first complaint was against the fact that many (45%) of the professors have PhDs outside of ancient scripture, but now you are saying that “education degrees are crap when it comes to teaching ancient religious history.” If you are going to teach ancient religious history you had better have a degree, or no one will take you seriously. It is not so much that you have the degree, but what the individual does with that degree. As I also stated above, we could ask to what extent the individual scholars are actually involved in their fields outside of the LDS realm. For example, Jared Ludlow’s experience being on the Enoch Seminar, or David Seely finishing the Anchor Bible Commentary on Deuteronomy for his friend Moshe Weinfeld, or others. We would also want to ask what papers they have recently presented at conferences, and what scholars they work closely with that are non-Mormon and the projects they are doing together. These kinds of questions are important.

I would also add that I did make it clear above that what you and I would expect of the Religious Education department at BYU might not fit the purpose, or raison d’être, of the department. This is an important point that you have yet failed to recognize or comment on.