By Sheldon Greaves, Ph.D.

One of the things that make the character of Abraham so interesting is when his behavior is a little less than ideal. Tradition and legends that grew up around him emphasize his generosity, his concern for the vulnerable and, perhaps most of all, his hospitality.

Hospitality was a very big deal not only in the Bible, but across the ancient world. Seeing to the needs of the stranger at your tent or at your gate was the one big test to see if someone was truly righteous or even civilized. If you showed hospitality, you were marked for divine favor. Flout those same institutions, and you could expect an ignominious end, a swift burial, and a watercolor epitaph. Or fire from heaven.

That’s why it should come as no surprise that when Abraham shows lavish hospitality to the messengers, it’s immediately followed by the news that Sarah will miraculously bear a son. But the same token, the violation of the norms of hospitality on the part of the men of Sodom is intended to explain why God turned the city into a smoking hole in the ground.

Canaanite Hospitality

But Abraham had his own difficulties with hospitality. It happens in the story found in Genesis 20 about when he and Sarah moved to Gerar. This story is a little out of place; Sarah is not old or, if she is, she’s still quite the looker; a real one-round knockout (The version of this story from the Genesis Apocryphon from the Dead Sea Scrolls goes into almost lurid detail about Sarah’s beauty, which makes sense considering that the document came from a community of celibate men).

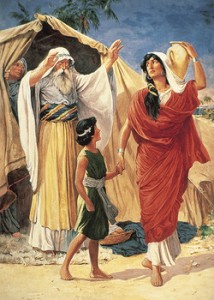

Abraham moves to Gerar with some unfounded assumptions in mind about the people there. They are Canaanites. He clearly thinks that they cannot be trusted to behave themselves, and fears that the local King Abimelech will decide he wants Sarah, and is willing to kill her husband to get her. So, Abraham instructs Sarah to say that she is Abraham’s sister. Technically, this is true; she was his half-sister. This way, if Abimelech wants Sarah, he need only make a deal with Abraham—presumably one he can’t refuse, but he’ll still be alive.

Abimelech takes Sarah into his household; Rank Hath Its Privilege. Things start to go downhill from there; suddenly all the women in the household have stopped having kids, and for some reason, the King can’t make it with Sarah. It just doesn’t happen.

Adultery is serious business, even for a king (See: David and Bathsheba). The King is also perilously close to violating the norms of hospitality, which is about the worst thing you can do; not only is he about to commit adultery, he is about to do so with the wife of what amounts to a guest in his land, which makes it even worse. This is cause for divine annihilation.

God warns the King in a dream that he’s messing with a married woman, and if he doesn’t give her back things will really get nasty. Horrified, the King does so. The King sends gifts, Abraham prays that God will take the bad mojo away, and Abimelech’s other wives start having kids again.

This is not Abraham’s finest moment. Let’s look at all the ways he’s messed up:

- He mischaracterizes the nature of the land, it’s people, and King

- He lies about the status of Sarah, at best hiding behind a technicality

- He puts Sarah is a decidedly awkward position

- Abimelech gains some power over Abraham because of his missteps

The King only does what kings do, but is sufficiently righteous that he enjoys God’s protection. God communicates with him directly, and tells the King in as many words that they are innocent.

There are several proposed “takeaway” points made by later interpreters, chief among which is the notion that the people God works through are not always the best of people, along with the implicit warning not to assume too much about other people’s motives and righteousness.

Tactical Gift-Giving

What’s really interesting about this little episode is the political resolution. Abimelech gives some serious gifts to Abraham. But since Abimelech is clearly the innocent and injured party, why is he coughing up all the loot?

Gift-giving in the ancient Near East was a rather complex political practice used to establish and regulate relationships. Now what happens next is a little off-topic, but it’s a fascinating peek into the world of the ancient Near East. Gift-giving was a way of establishing relationships. It was a form of bonding, but it could also be used in an aggressive way. Gifts were generally exchanged between equals as a way to establish a relationship.

To accept a gift is to accept certain obligations connected with it, starting with the requirement to reciprocate. If you don’t match the gift, you insult the giver, and you don’t do yourself any favors either.

Sometimes, someone will offer a gift that is impossible for the receiver to repay. In this case, the receiver becomes bound and even subject to the giver until such time, if any, that they can reciprocate.

So Abraham gets his wife back, and the Royal Household regains its fertility. Fair trade. But the king gives an additional huge gift of livestock and slaves to Abraham, plus 1,000 pieces of silver (an enormous sum). Why is the innocent party paying all this money? And why does Abraham not reciprocate?

The silver is to secure a favor; Abimelech tells Sarah a bit sarcastically that the gift is for “your brother” who reciprocates by abandoning all claims against the King pertaining to Sarah. The second gift, which Abraham does not reciprocate, renders Abraham into a subject of Abimelech. It is tied to a promise exacted later from Abraham that he will in no wise do any more of this nonsense ever again. Thereafter, Abraham is quite docile with regard to the King, and does not push the boundaries beyond what is reasonable.

Cultural background like this makes a perplexing story into a fascinating window on the thrust and parry of politics and power from a distant time.

Sheldon Greaves, Ph.D. is the host of “Discovering the Old Testament,” a weekly podcast that examines the historical, cultural, linguistic, and archaeological background of the Old Testament. He is also an adjunct instructor at Stanford University where he is currently teaching a class on the Dead Sea Scrolls. Sheldon, along with his spouse Dr. Denise Greaves, is a Scholar-in-Residence at Christ Church Episcopal in Portola Valley, CA.

Listen to “Discovering the Old Testament” via http://www.lafkospress.com.

Why is this even posted here? The guy is a Scholar-in-Residence at Christ Church Episcopal in Portola Valley, so his work totally ignores the additional information in the PoGP about this, making his article irrelevant to Mormons.

This is a rude comment.

P.A., would you like to explain exactly how bringing in the Book of Abraham would have helped Sheldon’s piece? The narrative about Abimelech is not found in the Book of Abraham, and the closest the text gets to Sheldon’s work here would be Abraham 2:21-25, but stops short of Abraham actually doing anything that would pertain to Sheldon’s piece.

If you could offer a few thoughts on how he could improve, that would be appreciated. If you cannot provide any, I would suggest keeping your thoughts about Sheldon’s appointments to yourself. If more information that provides a better understanding of Genesis is irrelevant to Mormons then you are living a different Mormonism than I am, and am participating with different Mormons than I am.

Thank you for these insights. I am trying to understand this and the other essay about Abraham. But I find this fascinating, and I appreciate your work.

oh, I’m the same person who just posted. I don’t pretend to be a competent critic. I have wondered about these things when reading the scriptures in the past, however, so I appreciate it when someone who has extensive experience in such an area offers his/her expertise.

Thought-provoking. I’m sorry that I can’t really contribute much to any real discussion, but I can remember, even as a child, wondering why Abraham had to lie.

Understanding the culture of a time period or area is extremely important, I believe.

My bad, I mixed up Gen 12 and Gen 20, so the PoGP doesn’t actually help any with this event, not directly at least.

If he was discussing the events of Gen 12 I would say the same thing though. It isn’t a slight against him or his work, just recognition that he would have been working without some of the facts of the story available to Mormons, so his work would not have been so relevant. A valid position to take in such circumstances.

I would agree here, but I would be careful to double check things in the future. As well, bringing up Sheldon’s appointment at Christ Church has no relevance for the validity of the argument he is presenting. I would stay away from bringing that up in the future, not only with Sheldon, but with other individuals who share important information on the Bible.

Withholding information is not lying.

If you really can’t buy into that, then consider the fact that killing a person to save a life is perfectly OK. When then would telling a lie to save a life be wrong? If Anne Frank was hiding in your attic and the Nazi’s were asking you if you knew of any Jews in the area, would you rat her out or lie to the Nazis?

This is different. Abraham assumes, as Sheldon points out, that Abimelech would kill him. This does not mean that Abimelech would have killed him. This makes the analogy to WWII mute. Abraham does make a mistake because he assumes too much, rather than giving Abimelech the benefit of the doubt. He assumed that Canaanites were all wicked, and therefore made the mistake of assuming all individuals in a group were the exact same. We can learn a lot from that lesson in our world today.