Jared Anderson

© 2012

Jewish Scriptures

Creation

Our word-saturated world renders it difficult for us to conceptualize the level of orality and lack of literacy that prevailed in antiquity. Only a small percentage of the population could read or write (basically scribes, those whose job it was to do so) and works were not written down without compelling reasons. This context must inform our reconstruction of the formation of the books that make up the Hebrew Bible. The complexity of composition defies simple points on a timeline. Imagine the following analogy: A professor puts together a book using class notes that his teacher took while in graduate school, in a class from yet another professor. This book goes through multiple editions, then is translated from German to English, after which it is revised by still another author. Who wrote this book? Which form is the official one? Our little example might span decades, but the books of the Hebrew Bible were composed, edited, augmented, and reshaped over centuries, sometimes over a thousand years. Books that were completed after the exile likely preserve traditions hundreds of years older. The dual tensions of composition in antiquity were to preserve as much as possible, but to innovate and update as necessary. With those caveats in mind, I will touch on a few points of the Bible’s formation.

Two poems of victory, the “Song of Deborah” preserved in Judges 5 and the “Song of Moses” in Exodus 15, give us our oldest parts of the Jewish Scriptures. The archaic Hebrew of these songs and other features indicate that these go back to the formative period of Israelite history, around 1200-1000 BCE.

Solomon’s reign (960-920 BCE) is a likely time for some earlier traditions to be put into writing for the first time. The bureaucracy he established and the efforts to build up his kingdom would have required scribes and records, and his ties to Egypt (he married the Pharaoh’s daughter) would have provided a means for him to do so. Some of the earliest psalms come from this period, and possibly some legal and narrative material now in the Pentateuch.

Though other books contain earlier traditions, Amos claims the status of the oldest book in the Bible, written in the early- to mid-eighth century BCE (788-750), followed by Hosea. Prophetic pronouncements mark an important stage in the formation of the Bible–by claiming divine authority for their words, the prophets marked their pronouncements as authoritative “thus says Yahweh.” These oracles would have been written down later by disciples. The statement “two years before the earthquake” (Amos 1:1) suggests that this earthquake was seen as fulfilling Amos’ predictions of judgment, which motivated people to write down his oracles. Hosea and Amos both preached in the North.

The impending destruction of the Northern Kingdom could have motivated scribes and priests to put their traditions in writing. After the destruction of Israel, many would have fled south to Judah, introducing the Southern Kingdom to the writings of the North. Isaiah was an influential prophet in Judea; his ministry covered a span of over forty years (about 740-698 BCE) in the context of regional wars that led to the destruction of the Northern Kingdom Israel. Given his status, it is likely that his oracles were written down during his lifetime and worked into the book that bears his name by later followers.

Another development important to the idea of scripture involved the attribution of laws to God. Taking ancient Near Eastern laws similar to the code of Hammurabi and then adding “Yahweh says” was an innovation that increased the authority of those laws. Josiah’s reforms in 622 BCE also marked a key point in the development of the Bible. The Deuteronomist may have embellished the event, but Josiah placing himself and his people under the authority of the “Book of the Law” found in the temple was a large step towards the status of sacred authoritative text.

Zephaniah preached a message of loyalty to Yahweh during the reign of Josiah (640-609 BCE); Nahum interprets the fall of Nineveh in 612 BCE to demonstrate Yahweh’s control over history, and Habakkuk prophesied immediately before the first Babylonian deportation of 597 BCE. An early version of the Deuteronomistic History was likely composed during Josiah’s reign, and the Bible makes mention of multiple sources now lost to us, such as the Annals of the Kings of Israel (see 1 Kings 15-16).

These developments lead us to the great literary activity of the Babylonian exile, where a large portion of the Hebrew Bible was composed or edited in only half a century. Ezekiel was composed in Babylon at the beginning of the exile. Though Jeremiah was active just before and in the beginning of the exile, his book was likely compiled during and shortly after the exile. We are fortunate to have an unusually clear understanding of this book. We know that Jeremiah was commanded to write down his oracles and deliver them to the king (chapter 36). Chapters 1-25 seem to parallel this early form of Jeremiah, which was dictated to Baruch his scribe. We have found bullae likely belonging to Baruch and have the signature and even fingerprint of one of the biblical authors. Thus an early form of Jeremiah existed in about 604 BCE (King Jehoiakim burned the scroll delivered to him, but Jeremiah redictated the material to Baruch). It is rare that we can discern the composition of a biblical book in such detail. Other parts of Jeremiah, such as duplicate passages and material organized by catch-words, suggest a long process of editing after Jeremiah’s lifetime.

One of the greatest writers of the exile remains anonymous, as he took up the name of the prophet Isaiah. Historical indicators make clear that Deutero-Isaiah (40-56) was written toward the end of the exile. We know that the Deuteronomistic History was updated during the exile, and most scholars also date much of the Priestly material in the Pentateuch to the Exile, though the final form of “P” is postexilic.

If much was written during the exile, the postexilic period is when things really start to come together. We can date Haggai with pinpoint precision–he writes during the drought of 520 BCE. Zechariah was written around the same time, 518 BCE. The scholar Armin Lange suggested there was a Deuteronomistic redaction of Jeremiah that took up Jeremiah’s mantle to confront the Zion theology of Haggai and Zechariah, preserved most clearly in the “temple speech” of Jeremiah 7 (DtrJer likely expanded a speech by Jeremiah). Third Isaiah was also written sometime around the construction of the temple in 515 BCE. Jean-Louis Ska argued that the Pentateuch was largely composed in the postexilic period, that it is at this time that earlier disparate traditions were woven together to form a national narrative and ritualistic guidelines. The “book of the Law” that Ezekiel read was likely a Priestly form of the legal material in the Pentateuch.

As you can see in the timeline below, the books of Chronicles, Ezra, Nehemiah, Esther, Proverbs, Ecclesiastes, Ruth, and the Song of Songs are difficult to date, falling somewhere in the window of the fifth to the third centuries BCE. The book of Psalms has one of the longest histories of composition, with songs that date to the time of Solomon and with the final form of the book still in flux in the second century.

As we finish up the Hebrew Bible with Daniel, we are once again on rock-solid dating. Drawing upon older traditions as virtually all books did, the final form of Daniel was composed in the midst of the persecutions of Antiochus Epiphanes IV, in Jerusalem in about 165 BCE. Thus the Hebrew Bible was written during a period of over a thousand years.

Copying

As the Septuagint and Dead Sea Scrolls make clear, the boundaries between composition and copying of the scriptures remain fluid. Jeremiah provides an excellent example of this fluidity: the form of the book copied in the Septuagint is one-eighth shorter than the version we have in Hebrew and actually preserves an earlier edition of Jeremiah.

The books of the Bible, like all books, had to be copied by hand, a letter at a time. Thus on top of centuries of editing, the Bible endured further millennia of transcription before arriving at the manuscripts available to us today.

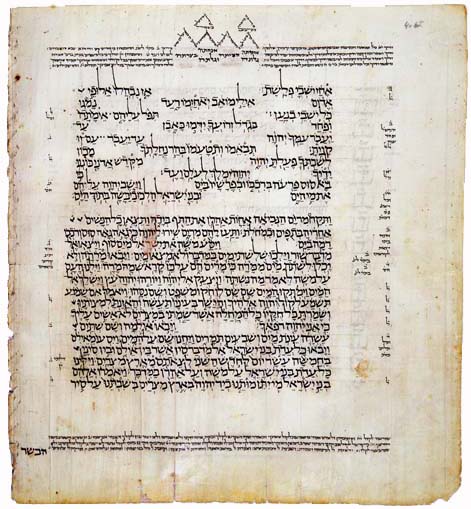

To the left is an image of our oldest witness of the Hebrew Bible, copied before many of the books of the Bible were written! It dates to the last quarter of the seventh century BCE (625-600) and contains the Priestly Blessing found in Numbers 6:24-26. Look carefully at the letters, which are an older form of Hebrew (the modern Hebrew alphabet is actually Aramaic or square script).

To the left is an image of our oldest witness of the Hebrew Bible, copied before many of the books of the Bible were written! It dates to the last quarter of the seventh century BCE (625-600) and contains the Priestly Blessing found in Numbers 6:24-26. Look carefully at the letters, which are an older form of Hebrew (the modern Hebrew alphabet is actually Aramaic or square script).

(Image source: The Israel Museum, Jerusalem)

In our discussion of the copying of the Jewish Scriptures, we will touch on three forms of the text of the Hebrew Bible: the Masoretic Text (MT), the Septuagint (the LXX), and the Samaritan Pentateuch (SP). By forms of the text, I mean that each of these versions has distinct readings and characters, words, or phrases that are in one form but not another.

Masoretic Text

Most modern editions of the Jewish Scriptures are based on the extraordinary work of medieval scribes called the Masoretes. These families from about 600-1000 CE perfected a long tradition of meticulous copying of the biblical texts. The Masorah refers to the system of vowel signs, accent markings, and marginal notes to communicate how to read the consonantal text of the Hebrew Bible. (Hebrew does not have vowels, so markings are placed around the consonants. So “David” would be written “DVD,” with markings below and above to mark the “a” and “i” sounds.) The meticulous care of the Masoretes can be demonstrated by notes that indicate how many times a particular word or combination of words appears in the entire Hebrew Bible, which words only occur once, and even what the middle word is of each biblical book. Such measures ensured the accurate copying of the manuscripts. The Dead Sea Scrolls vindicate the work of the Masoretes in large part; manuscripts over a thousand years older than those annotated by the Masoretes are virtually identical to their later descendents (there are also DSS MSS, “Dead Sea Scrolls manuscripts,” that align with the LXX and SP).

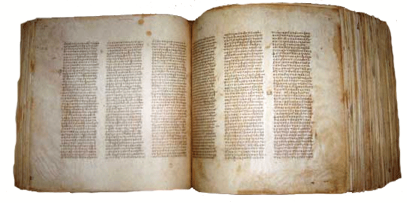

Below is an image of Leningradensis, the manuscript of the Hebrew Bible underlying most modern translations. It was copied in 1009 CE by Aaron ben Asher.

(Image source: Pekka Pitkänen’s Old Testament Studies Site)

Septuagint

The Septuagint (LXX) refers to the Greek translation of the Hebrew Bible made in the second and third centuries BCE. It has its own complex textual history, with many revisions, many of which brought the text closer to that of the Hebrew. The Septuagint is a valuable witness to the text of the Hebrew Bible, but first scholars need to penetrate the translation itself. The translation of some books is wooden to the point of being bad Greek; translators of other books felt free to update and change the text (Isaiah is an example). The Septuagint became the Old Testament of Christianity, so the most famous copies of the Septuagint are the great Christian bibles of the fourth century CE. Our oldest fragments from the LXX are among the Dead Sea Scrolls.

Samaritan Pentateuch

The Samaritans, the descendents of the scattered northern tribes and transplanted Assyrians, follow a religion close to but distinct from Judaism. Their worship centered on Mount Gerizim, near Shechem. They recognized only the Pentateuch as scripture. Copies of the Samaritan Pentateuch differ from the MT, and forms of this text have been found among the DSS (without the idiosyncrasies of the SP, such as the focus on Mt. Gerizim).

Dead Sea Scrolls

To say that the Dead Sea Scrolls are the most important find for our understanding of the text of the Hebrew Bible and Second Temple Judaism is not an exaggeration. The first scrolls were discovered by a Bedoin boy looking for his lost goat, and eventually about 900 manuscripts were brought to light, 200 of those containing biblical text. They also contain extra-canonical texts, commentaries, and fascinating works such as rewritten biblical books (the Temple Scroll is adapted from the Pentateuch, but put into first person from God’s own perspective!). These manuscripts date from the second and first centuries BCE, and therefore are over a thousand years older than our oldest previously known copies. One of our oldest scrolls, a fragment from Daniel (4QDanb), was copied within decades of when the book was written. These manuscripts attest to a time when the text of the Hebrew Bible was more fluid, though about 45 percent of them still align with the text preserved in the Masoretic tradition; about 3-4 percent match the Hebrew behind the Septuagint, and 6.5 percent with the Samaritan Pentateuch.

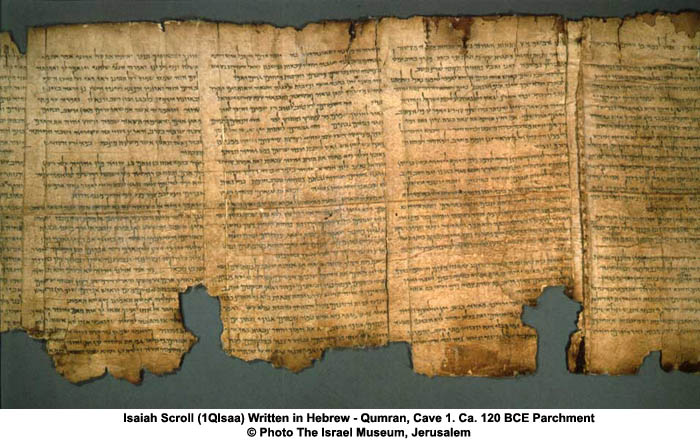

Below is a picture of the Great Isaiah Scroll, one of the best-preserved manuscripts among the scrolls, and dated to about 120 BCE.

Canon

“Canon” (from a Greek word meaning “rule” or standard”) refers to an authoritative collection of texts; in this case, which books belong in the Bible and which are out? The path of the biblical books gaining the status of authoritative scripture can be outlined as follows:

- Law and prophets in the eighth century BCE

- Josiah’s Deuteronomy

- Law and prophets during the Babylonian Exile

- Until the Hellenistic religious reforms, biblical books gain increasing authority

- In Maccabean times, the concept of scripture evolves

- After 70 CE (the destruction of the Second Temple), numbers of scriptural books are given.

Now let’s unpack that.

Law and prophets in the eighth century BCE

We have touched upon the fact that from about the eighth century BCE, prophets claimed to speak the words of Yahweh, and laws were also attributed to God. This innovative claim of divine authority obviously increased the status of oracle and law. Prophetic pronouncements and divine law put into writing laid the foundation for scripture and would become some of the earliest sacred texts and collections.

Josiah’s Deuteronomy

Josiah based his religious reforms on an early form of part of Deuteronomy (the “D” source). As best we can tell, this text was written specifically for this reform, but it is significant that Josiah himself covenanted to follow its teachings and bound his people to do the same. Everyone and everything is subject to this law: “Keep these words … in your heart. Recite them to your children and talk about them when you are at home and when you are away, when you lie down and when you rise. Bind them as a sign on your hand, fix them as an emblem on your forehead and write them on the doorposts of your house and on your gates” (Deuteronomy 6:6-9). This is powerful rhetoric, and the official establishment of this text as a binding document of divine provenance represents an important step towards the biblical texts being viewed as scripture.

Law and prophets during the Babylonian exile

The destruction of Jerusalem and the temple turned Judean society upside down and placed them in the midst of the powerful and alluring Babylonian culture. The Jews needed a way to maintain their distinct cultural identity and traditions. Bereft of king, state, and temple, they turned to their texts—the law provided their cultural identity. They turned to their cultic traditions and prophetic pronouncements as the core of their religious observance, and these factors increased the status of these texts tremendously.

Until the Hellenistic religious reforms, biblical books gain increasing authority

The Persians authorized the laws of their subjects, and this seems to be what is going on in the book of Ezra. Ezra read a copy of the Torah, which was likely some form of the Priestly legal traditions in the Pentateuch. This was another step toward scripture. Until the second century, religious texts continued to gain greater authority.

In Maccabean times, the concept of scripture evolves

All the previous factors increased the authority of religious texts significantly, but it was in the crucible of the Hellenistic Religious Reforms of Antiochus Epiphanes IV that scripture emerged in its full form. This development meant that the authority is in the text, the book itself, rather than just the divine law or prophetic word. After 175 BCE, exegetical literature developed and there began to be quotations of and allusions to the biblical books, as Armin Lange illustrates. The first “canon” lists also develop during this time, such as in the prologue of Ben Sirach.

After 70 CE (the destruction of the Second Temple), numbers of scriptural books are given

After another cultural cataclysm, the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE, scripture gained even more importance and authority. At this point the text of the Hebrew Bible became fixed (we no longer see the variation evident in the DSS), and specific lists were given of which books belonged in the Bible and which did not. The Jewish historian Josephus mentioned a master copy of the Hebrew Bible in the temple, which suggests an official stand on canon (Antiquities 3:38, 5:61), and stated that twenty-two books were sacred (against Apion I:36-47):

- five of Moses: Genesis-Deuteronomy

- thirteen prophets: Joshua, Judges, Ruth, 1 Samuel-2 Kings, 1-2 Chronicles, Ezra-Nehemiah, Job, Esther, Isaiah, Jeremiah and Lamentations, Ezekiel, XII (Hosea-Malachi), and Dan

- four other books: Psalms, Proverbs, Song of Solomon, and Ecclesiastes

Rabbinic discussions debate the status of a few books here and there, such as Ecclesiastes and Esther, but the canon seems to have been mostly in place by the first century CE.

Of course, given that the Septuagint contains different books than the Hebrew Bible, and that different religious traditions adopted each of these, each community has needed to determine its own canon.

Information found in Jared’s post come from his online courses through the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. Anyone can take these courses. If you are interested, click here.

Jared,

The first few questions I have deal with the last post; Then I have some questions regarding this post. I figured it would be easier for you to deal with them all on the same post, as opposed to hopping around. Thanks for the links and the book recommendation. I am sure my wife will be excited about me buying yet another book; I will blame you.

1) It seems that the “J” source for the O.T. would account for the Mormon anthropormorphic God, and the other sources would account for the “orthodox/traditional” Christian view of God. Am I barking up the right tree?

2) When speaking of redaction, does that mean adding too, taking away from, and connecting different sources together?

3)You used the term “archaic” language when referring to some of the texts. Will you give an example that I would understand?

4)You spoke of one of the texts found in the Dead Sea Scrolls being 1/8 shorter than other texts. Will you be more explicit? Does it just leave out some of the writings that other manuscripts have?

5)You spoke of “historical indicators” when dating material. Will you provide an example?

6) When you speak of a text being “more fluid”, what does that mean exactly? It’s easier to change without people taking issue with the changes?

7) In the New Testament Gospels we find Jesus quoting Hebrew Scripture. Am I to understand that the Hebrew scripture had not been cannonized yet?

8) Later are you going to discuss why the King James translators relied on the Masoretic text as opposed to the LXX?

9) Please clarify what these mean: MSS (Masoretic Text?) DSS (Dead Sea Scrolls?) SP (Samaritan Pentateuch?)

10)Is it your view that the Northern Kindgom’s and Southern Kingdom’s literature developed independently from eachother and then came together later? Does this mean that the two were not related to eachother as the Old Testament teaches?

11)Why do scholars not take the Hebrew text at face value and assume it was written chronologically as we have it in the Bible? I am not sure if I asked that question right.

12) How do people who hold the Bible to be inerrant and infallible view what you have said in your post?

Mike

Ok, I am done with my grading so I can get to these questions!

Feel free to blame me for any book purchases. 🙂

1) You are in the right forest. My hunch is that there are differing tendencies in human nature when it comes to understanding or describing God—sometimes people want to stress that God is like us, other times they want to emphasize his transcendence. There are traditions within the Bible that back up both. So it isn’t a question of direct dependence but rather that these narratives are wrestling with the same issues about God that Mormonism and Orthodox Christianity are (though the hyperliteralism of Mormonism has its own intellectual history of course)

2) Redaction is a fancy word for editing. So all of the above.

3) When I said archaic I was referring to an older form of the Hebrew language. There are differences just as you can distinguish Chaucer from Shakespeare from modern authors. So sections like Exodus 15 and Judges 5 are closer to our old Ugaritic texts, just like middle English is closer to Old English.

4) The text is Jeremiah, and both the Septuagint (the Greek translation of the Jewish scriptures) and a manuscript among the Dead Sea Scrolls are both an eighth shorter than the standard Hebrew text (The Masoretic text, which is the official Jewish version, basis for all translations etc). It seems to represent an earlier literary edition of Jeremiah, and then the Hebrew edition has sections rearranged and content added.

5) I tell students to look at the details provided in the scriptures and ask “When am I? What historical period is presupposed?” I will give a few examples. Isaiah 45 refers to Cyrus as a Messiah, and Cyrus conquered Babylon in 539, issued a decree the Jews could return in 538, and the Jews returned in about 520. So Isaiah 40-55 had to be written in that window. Then Isaiah 56-66 presupposes that they are back in Judah but the temple hadn’t been finished yet, so those details put that section around 520. Haggai gives precise dates for his book so we can date it to the sixth through ninth months of 520 (1:1 “In the second year of King Darius, in the sixth month, on the first day of the month, the word of the Lord came by the prophet Haggai…”). The Book of Daniel can be dated with a high level of accuracy… it talks about an abomination in the temple and a large golden statue a king commanded them to worship, and Antiochus Epiphanes IV set up a statue in 167 BCE, so the book had to be written after that (at least the *final form* of the book which is an important distinction. Most books of the Bible have a long history of composition and draw on earlier traditions). Then Daniel 11 predicts the death of Antiochus, but gets it WRONG. Antiochus died in 165, therefore Daniel was finished between 167-165, probably in about 165. (the Book of Daniel pretends to be written in the 500s in Babylon but its actual historical context is quite clear).

6) Exactly. Views toward these texts changed over time. Before the end of the first century scribes felt entitled to change the text—there are multiple examples of the “rewritten Bible” genre among the Dead Sea Scrolls, including the Temple Scroll which retells the first books of the Bible from God’s perspective! So scribes felt they could update the books as much as they needed… it wasn’t until the temple was destroyed that one textual form seems to be seen as holy and unable to be changed.

7) The Jewish scriptures were not canonized in the form we have them yet. As I note in the NT section, Jesus refers to the “Law, Prophets, and Psalms” which would represent an earlier form of the Canon. The Law and Prophets were pretty set in Jesus’ time and there remained some debates about books in the section called the “Writings.” For example, at the end of the first century CE rabbis debated whether the book of Esther was scripture.

8) No, I don’t go that far in the history of translation, just up to canonization. The short answer was they were Protestants. 🙂 When Jerome translated the Bible into Latin, he mostly used the Greek Septuagint. The Greek Orthodox Church uses the Septuagint (as did most early Christians). But with the Protestant Reformation there was a big push to go back to the “pure originals” so translations began to draw from the Hebrew and Greek. William Tyndale, one of my heroes was killed in 1536 for translating the Bible from Hebrew and Greek into English—he was the first to do so. Does that answer your question?

9) Good guesses.

MSS: manuscripts (Masoretic Text is MT)

DSS: Dead Sea Scrolls

SP: Samaritan Pentateuch.

10) It is more complicated than that; there was a great deal of cultural (and thus literary) mixing not only between Israel and Judah but also with the wider cultures such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, Ugarit etc.

11) Because first, a close reading of the Bible gives plenty of indicators that we cannot take the chronology at face value (thinkers picked up on these hints very early, Spinoza comes to mind), and second, we can put together a plausible history of how the Bible came to be in its current order that makes more sense.

12) I imagine they would dismiss it. I find Biblical inerrancy untenable; my motivation to publish about the history of the Bible has to do with problematizing (in a productive way) the nature of scripture, revelation, etc.

Great questions!

Reading through your questions again underscored the fact these are questions that delight my professorial heart.

I answered the inerrancy question too quickly. Hard line inerrantists would be dismissive, but more middle-way and informed inerrantists would appeal to Provedance and say that God was overseeing that complicated process to ensure the Bible ended up as He wanted. Or say that the Bible was only perfect at an earlier form, usually the originals of the final form of the Biblical books. It gets problematic very quickly.

Jared,

Before I go on to ask you questions about your New Testament time-line. I have more questions regarding the answers you gave to my Old Testament questions.

1) Regarding the time line presented in the Old Testament. Are you arguing that the time-line provided by textual critics is more plausible than that provided by biblical inerrantists?

2) I have heard of the Daniel dating problem before. Cannot the argument be made regarding Antiochus’ death, that a later redactor re-wrote the prophecy wrong? Thus making an argument for Daniel 11 being written (originally) in the 500s?

3) Why would one regard the Old Testament as providing any historical reliability at all? How does it compare to other ancient texts/inscriptions? The reason for the question is that it seems that textual critics will rely on some dates (an example would be your example of Haggai 1:1) but then question other dates such as the dating of Daniel based upon “an obomination in the temple.” Cannot the latter be argued to be a prophecy and not necessarily contemporary with Antiocus Epiphanes IV? Of course this pre-supposes an omnipotent God.

My New Testament questions will follow the same line of skepticism. I appreciate you answering my questions. It is a rare opportunity for me. I believe Mormonism has the ability to look at these questions more critically than Protestants because of our view of “the Bible being the word of God as far as it is translated correctly.” However, I do get annoyed with my fellow parishoners when they too readily throw the Bible under the bus in an attempt to justify the necessity of the Book of Mormon.

mike

With all the complexities in how the bible was compiled, and the way in which the texts may have been interpreted and changed by multiple scribes, it’s pretty tempting to say, “what’s the value of studying a book with such a questionable history”. Or, “What value can be placed in teachings that may have been changed each time they were touched by a new scribe”. Or perhaps, “It’s an interesting book, but the content is man-made rather than divine. How would you respond?

These are very important questions m.rees, and address the theological connection of the intersection of divinity and history, of divine will and human agency. How much does God influence us? Does God override us?

I personally would not expect scripture to be anything but messy and human, but at the same time infused with inspiration and something nobler and transcendent.

At the same time, there is harmful material in the scriptures that we must be free to call it on. We must be able to apply ethical critique to the scriptures. I think God wants us to, saying in effect, “This is the best that people thousands of years ago could do; now I invite you to do better, take it to the next level.”

I find pragmatism or utilitarianism to be tremendously helpful in evaluating the value of scripture. Whatever their history, we can judge the ideas by their fruits, but the demonstrable benefits of the ideas contained therein.

That said, it is also helpful to understand the history in order to apply it to theological questions.