Eternity, when put into proper perspective, is a most terrifying concept. As a child, my sister would occasionally suffer from late-night bouts of anxiety as her young, imaginative mind contemplated what we might refer to as “the eternities.”

“I don’t want to go to Heaven!” she would sob desperately, tears streaming down her face. “There’s nothing to do there! It sounds so boring! I don’t want to live forever!”

I’d be lying if I said I didn’t get a good chuckle out of all this at the time. I mean, of all things to be afraid of! It’s something that my family and I still gently tease her about to this day.

But reading A Short Stay in Hell by BYU professor Steven Peck, although not about Heaven per se, persuaded me that perhaps my sister was onto something. Indeed, in all the discussions I’ve seen about this fascinating novella, there is one adjective that never fails to come up: haunting.

Soren Johansson is a typical middle-aged Mormon man who, upon dying of brain cancer, finds the afterlife to be quite unlike what he was expecting. In a scene reminiscent of that one episode of South Park* wherein a large group of dead people is disappointed to find out that Mormonism was the correct religion, Soren finds himself consigned to Hell because, as it happens, the correct religion on Earth was Zoroastrianism, and (obviously) only Zoroastrians are eligible for Heaven.

The title of this book is ironic, because by our standards, Soren’s stay in Hell turns out to be anything but short. This is just one of several clever ways in which the author assists us in putting the concept of infinity – something our human minds are scarcely capable of grasping – into perspective. Rarely do we really consider what it might feel like to live forever. It is in some ways unfortunate that we are capable of using numerals to express extremely large numbers in a relatively condensed format, because by doing so we lose appreciation for their enormity. Consider this: no matter what finite span of time you can conceive of and no matter how large a number you can assign to it, it is dwarfed by eternity. If that isn’t a sobering thought, I suggest you give this book a read.

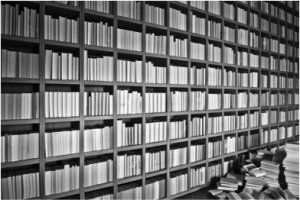

It turns out that there are several versions of Hell to which a damned soul might be sent, and Soren is assigned to one specially selected for him. This Hell’s setting is borrowed from a short story by Jorge Luis Borges called The Library of Babel. If you are familiar with the Library of Babel (I wasn’t), you will know that it is an enormous repository of books. In fact, enormous is an understatement: this library contains every single 410-page book that can possibly be written using standard characters. There is no requirement that the books make any kind of sense. Probability laws dictate that the vast majority of the library be comprised of complete and utter nonsense. Soren and many others who share his fate are placed in this library and told that they must stay there until they find the book that contains their own life story. Only once they accomplish this task will they be permitted to enter into Heaven.

Based on the above, you might assume this story is boring, but you’d be wrong – there is plenty to keep the reader hooked. I couldn’t put the book down. In fact, since it’s such a quick read, I read it twice.

Mormon readers will find certain themes that stand out as being particularly familiar (e.g. Hell is said to be “for your edification and wisdom,” and is temporary rather than eternal), but this is by no means simply a “Mormon book.” Rather, it deals with questions that reflexive thinkers of all stripes have pondered for as long as there has been such a thing as pondering. What gives our lives meaning? Is meaning dependent on something external of ourselves, or is it of our own making? Does certainty in an afterlife automatically confer meaning on our existence? Assuming you believe in an afterlife, what do you want it to be like? Is the idea of endless punishment consistent with the idea of a just God? Sometimes we Mormons talk and act as though we know a lot more about the afterlife than we really do, and Peck seems to be pushing back against that tendency. Perhaps we’re a little too cavalier in how we throw around terms like “eternal life.” Perhaps a bit more epistemic humility is in order. Perhaps many of our assumptions are just plain wrong.

But above all, what comes through most strongly is Peck’s vision of what it might mean to be in Hell. For Peck, Hell isn’t necessarily about being physically tortured or burned á la Dante’s Inferno (though physical pain does play a big role). Instead, we find a Hell that is about sameness, monotony, mundaneness. Eons and eons of it. It’s about near-endless corridors furnished with bland gray carpet, and shelves upon shelves of books containing mostly gibberish. There is no variation, no diversity. One of the first things Soren encounters in Hell are squeaky gray metallic folding chairs (anyone who has ever been late to Stake Conference knows what I’m talking about – the only thing missing from Hell’s decor is that prickly stuff they put on the walls in LDS chapel hallways). Also of note – Hell is full of other people, but they too are all the same. Intimate relationships are theoretically possible, but there is so little upon which to build them that it seems futile.

But above all, what comes through most strongly is Peck’s vision of what it might mean to be in Hell. For Peck, Hell isn’t necessarily about being physically tortured or burned á la Dante’s Inferno (though physical pain does play a big role). Instead, we find a Hell that is about sameness, monotony, mundaneness. Eons and eons of it. It’s about near-endless corridors furnished with bland gray carpet, and shelves upon shelves of books containing mostly gibberish. There is no variation, no diversity. One of the first things Soren encounters in Hell are squeaky gray metallic folding chairs (anyone who has ever been late to Stake Conference knows what I’m talking about – the only thing missing from Hell’s decor is that prickly stuff they put on the walls in LDS chapel hallways). Also of note – Hell is full of other people, but they too are all the same. Intimate relationships are theoretically possible, but there is so little upon which to build them that it seems futile.

In contrast to all this dreariness is an implicit invitation to reflect upon what Hell’s opposite might be. It was only as I considered this opposite angle that I found, masked by the monotony, an uplifting message about my own life and its value. So although I was haunted by this tale as it forced me to stare into the abyss of Hell, and, like my sister when she was a child, confront the possibility that eternity might not be all it’s cracked up to be, I was left with a feeling of deep appreciation for my own life and a renewed desire to make the most of it.

*In case you haven’t seen it, this scene occurs about 8:50 into the episode. Watch the rest at your own risk.

Thanks for the review. I will read this book! The real question: does it have 410 pages?

Great review. My husband had exactly the same childhood fears as your sister. At first I thought that was strange. Now I think he had much more respect for eternity than I did.