A dear friend, who I will call Jim, of my (former?) partner, and I, after the LDS church’s response to the decision of the U.S. Supreme Court on same-sex marriage and then the response to the decision by the Boy Scouts of America to allow inclusion of gay scouting leaders, sent a message to me, saying, among other things:

“You are now my life’s great mystery. Why you would break [your partner’s] heart and give up your manhood for this horrible, wretched, hateful crowd mystifies me. They have no respect for you or me or any gay person whatsoever. They make that clear at every juncture. Why can’t you just let go? It couldn’t be clearer that the Mormons don’t want gay people.”

How do you answer someone who loves you, and has for twenty years, and as an agnostic who was raised in a mainline Protestant faith, struggles to comprehend what could cause anyone to — in his view — give up everything in order to be part of a church hostile to gay people? Here is my attempt.

Dear Jim,

You and I were both raised in Christian religions with strong views about right and wrong, the nature of God, and the purpose of life. Since then, we have both been exposed to a much broader range of spiritual thinking, and have seen good and evil in the world, firsthand as well as at the distance of history.

I am certain neither of us sees the world the same way we did when we were eight, or fifteen, or even twenty-five. At the most basic level, as we have learned, had our perceptions challenged and stretched, experienced hard times and glorious times, we have had to synthesize our views of reality with our hopes and fears for a distant future and to come up with some kind of unifying theory of personal meaning.

That was what I meant when we were talking a few weeks ago and I said each of us chooses what we will believe and then, as we go along, we generally find things that will reinforce our choice, and also from time to time to challenge it, and so we keep refining and deepening what it is we have chosen to believe. Another name for that choice to believe is faith, which could be defined as trusting in something you cannot explicitly prove. (Paul, in his letter to the Hebrews said, “faith is the substance of things hoped for, the evidence of things not seen.”) In that sense, you and I both have faith, but our faith has different objects.

So, let me try to explain my faith.

I was raised in what I would call a devout Mormon family. My parents had strong faith in Jesus Christ, in the idea that God can and will continue to speak to His children, that He has once again called prophets and authorized them to administer ordinances necessary for salvation (such as baptism) and to speak in His name.

In my mid-twenties I could not see a place for a gay man in Mormondom, so I left. In so doing, some of my former beliefs, my faith, seemed no longer to apply and some beliefs just became dormant. At various times, I attended different churches and did some amount of study on world religions, but it seemed to me that simply trying to be a good person — one who was honest, kind, charitable, tried to avoid hurting others, and who might leave a small corner of the world a better place than he had found it — was a sufficient faith to embrace and follow.

In those years, I also comprehended faith in equal dignity based on my experience as a gay citizen of America in the bewildering early days of AIDS, as an employee of large corporations, as a neighbor in a community. I have faith that one skin color is not better than another, one gender is not superior, one sexual orientation of itself is not inherently right (or righteous).

And then, despite a very happy life, notwithstanding being incredibly fortunate in a career, being able to enjoy many of life’s satisfactions, and above all, the privilege of loving and being loved by an intelligent, gentle, warm-hearted man, I felt there must be more to life. As Langston Hughes wrote:

The ivory gods,

And the ebony gods,

And the gods of diamond and jade,

Sit silently on their temple shelves

While the people

Are afraid.

Yet the ivory gods,

And the ebony gods,

And the gods of diamond-jade,

Are only silly puppet gods

That the people themselves

Have made.(“Gods” by Langston Hughes)

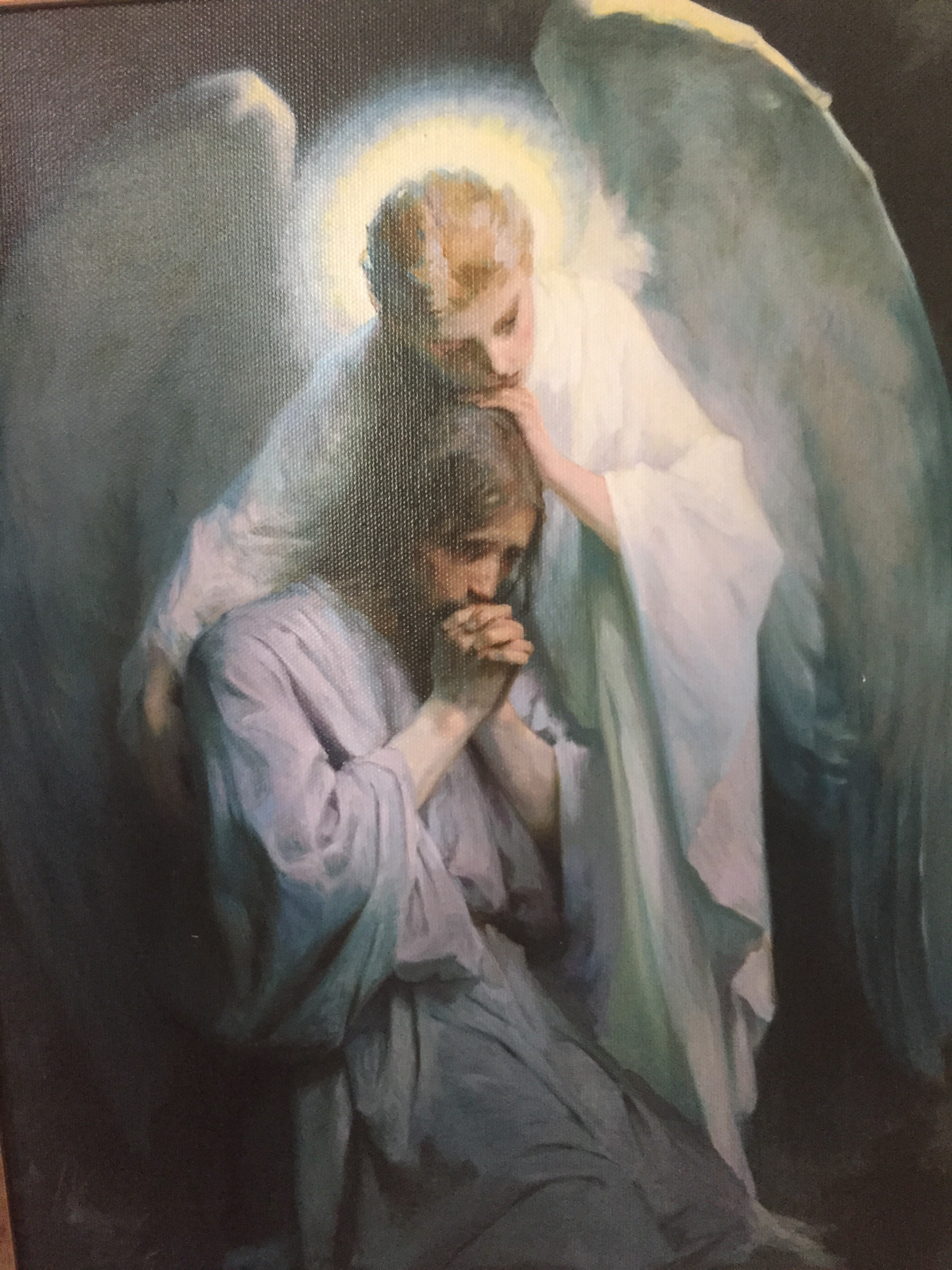

So for me, the “more” couldn’t be more of my own thinking, more philosophy, more good works, or more kindness, and prayer had to be more than meditation, it had to be access to the source, for direction, for guidance. And that is what I found in the faith of my childhood, not because it was familiar, like comfort food for the soul, not because it is the uniting bond of my family (although it is) but because unlike the dogmas I had absorbed along the way, there I found at least some of the answers to new questions arising from my life journey. In The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, Jesus Christ became very real to me. Not the diminishing platitudes: Master teacher, great prophet, authority of a universal moral code. But the only begotten Son of our Father, the only perfect man, who voluntarily atoned in the Garden of Gethsemane and on the cross for all sin and suffering that had occurred or ever would occur in the world.

“Which suffering caused myself, even God, the greatest of all, to tremble because of pain, and to bleed at every pore, and to suffer both body and spirit—and would that I might not drink the bitter cup, and shrink—

“Nevertheless, glory be to the Father, and I partook and finished my preparations unto the children of men”(Doctrine and Covenants 19:18-19)

To the center of my being, I know this is true. I know the only response I can possibly provide to His offering on my behalf is to do all that I can to make my life, the person I become, reflect the depth of my gratitude and love. To me, some of the most profound words of poetry to be found are those we sing in the hymn, “How Great Thou Art”:

“And when I think, that God, His Son not sparing;

Sent Him to die, I scarce can take it in;

That on the Cross, my burden gladly bearing,

He bled and died to take away my sin.

Then sings my soul, My Saviour God to Thee,

How great Thou Art, How great Thou Art!”(Carl Gustav Boberg, translated by Stuart K. Hine)

The Jewish writer Amy-Jill Levine calls the parables of the New Testament “short stories by Jesus”. I find two of them helpful in trying to convey what I have found:

The kingdom of heaven is like treasure hidden in a field. When a man found it, he hid it again, and then in his joy went and sold all that he had, and bought that field.

Again, the kingdom of heaven is like a merchant looking for fine pearls.

When he had found one of great value, he went away and sold everything he had and bought it.

(Matthew 13:44-46, NIV)

These two short parables teach the same lesson—the kingdom of heaven is of inestimable value. That kingdom where all will live again, where loved ones are reunited, where all knowledge is available, where perfect unity of hearts and minds is found, where poverty is not. The treasure and the pearl represent Jesus Christ and the salvation He offers. I can neither buy nor earn my way to that kingdom; rather, Jesus Christ has paid that price for all; to show my love and gratitude I am impelled to do all I can to become like Him.

Does that give you a glimpse of why for years I prayed that the person I love most in the world would also come to perceive what I had found? Over those years, as I traveled the path of feeling more and more drawn to the course of discipleship, I had assumed throughout this life I would be limited in the things I could do within this church because of the commitments I had made to my partner about our lives together. Because of his love for me, he said he would not stand in my way of becoming a member in good standing of this church. While I continue to hope and pray these two parts of my life can somehow be united, my partner’s love has made it possible for me to achieve at least one desire; my love for him means I daily plead with God for his happiness, wherever he may find it.

And so here we are: I am a member of a church that you see as horrible, wretched and hateful to gay people. And yet, I love my Latter-day Saint brothers and sisters for their eagerness to help one another and the wider world, I love them for their devotion to duty, I love them for their reverence for things sacred. As I love my gay brothers and sisters for their zest for life, I love their humor and sensitivity to others, I love their rainbow diversity and their optimism for a better tomorrow. I carry two passports; my heart holds North and South, and this war does not feel civil to me! I know as a church we can do better, we can be more expansive in our welcoming embrace and our loving acceptance. You said that it couldn’t be clearer that the Mormons don’t want gay people. But they need to want us, they need the courage we bring, they need our talent and loyalty. And we need the soul-stretching, the enlightening, we need our sights raised. I am far from perfect, but I can help in that effort simply by being a person with a North and South heart. I cannot stop loving either of my tribes. And I cannot stop praying they will learn to love each other. The path forward is not always clear, so by necessity as well as by choice, I walk in faith.

My purpose has not been to convince you, but I hope you might have some empathy for the depth of my feeling about this journey, and my sense that any price I may pay simply pales in comparison to the gift I have received.

With my love, and my deep gratitude for your friendship,

Tom

Thank you for your story. It is inspiring and encouraging, two things much needed in this discussion. Best Wishes…

I rarely comment, but thank you for sharing your experiences.

Tom, your faith is inspiring. Thank you!

Tom, thank you for your well-considered article. It is a courageous act to put so much intimate detail of your life in a blog post.

I wish you great happiness in your journey, and I’m deeply saddened that a man would feel the need to leave his loving and loved partner to achieve good standing with the church. Regrettably, this is why so many LGBT Mormons see no place for themselves in the church.

Again, I wish for you only the best.

I’m tired of waiting for a place at the table.

This was beautifully written and honestly made me cry a bit. Because of the beauty of the faith presented, but also because how sad it is. As a gay Mormon who has only in the past year come to terms with dating men and hoping to find a husband, this was a difficult story to hear.

I wish these kind of decisions weren’t so difficult to make, and that they didn’t, no matter what one’s choice of life direction, hurt so many people.

In the end we all choose our own path, and it’s never easy. I wish you and your former partner all the happiness you can find. I ache for you, because I often ache too.

Much love!

Thanks for an eloquent article. The reference to North and South reminded me of the Civil War, and the loyalty to conflicting institutions that ultimately drove humans to take each others lives. Challenging times lead to challenging decisions. May our devotion of the God of Truth and Love lead us to make these decisions for the right reasons; and seek continued understanding.

Thank you for sharing your feelings and your faith. As a bishop in the Mormon church it helps me better understand what others may be going through.