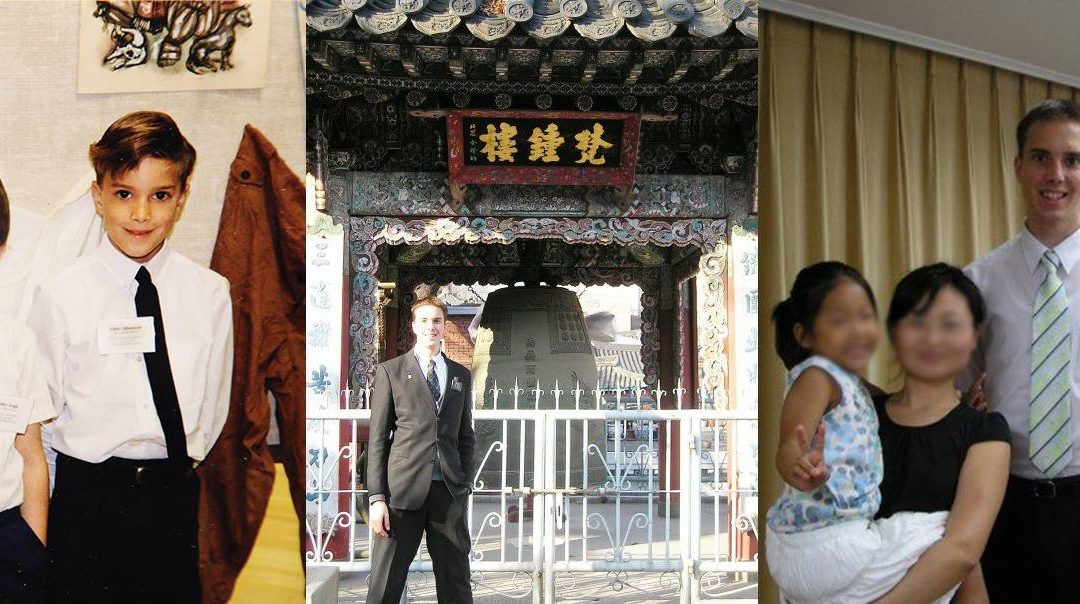

Last week, Josh and Lolly Weed announced their plans to divorce. Their names rose to Mormon fame when, in 2012, they “came-out” as a mixed-orientation couple: A faithful Mormon heterosexual woman married to a faithful homosexual man. Not only did it work, they said, but they were also incredibly happy. This is all that many members of the Mormon faithful needed to hear to justify the words said and actions taken by the leadership of their church concerning LGBT people.

When the Weeds “came-out,” I was still just beginning to navigate my way after painfully coming to terms with my own non-ordinary orientation. Having lived through the “Prop 8” era while at BYU and in the midst of high tensions between the Mormon church and the LGBT community, I knew all too well how their story would be weaponized against those like myself who decided that they had to honor who they were at their core, regardless of what it might cost them.

Josh Weed was held up as a standard for the righteous gay Mormon man. If he could do it, then it showed that the expectations set by the LDS Church could be justified. To be fair to Josh, he never intended for his story to be used this way. But for members of the Mormon church who are looking for a defense for their church’s position, stories like these are exactly the antidote to the discomfort they might feel about it.

One of the hardest parts about coming out was that most members of my Mormon community simply could not awknowledge my experience. In hindsight, I have some compassion now for their situation. I think that for them, acknowledging the reality of my experience would challenge the stability of their own belief structure. It raised too many questions that they couldn’t bare to ask. So rather than listen, they turned away. Despite the 25 years I was devoted to Mormonism, suddenly I was an enemy- and just as I was finally feeling hope for life again. It made me angry.

After some years, I slowly came to terms with the fact that I had to let go of Mormonism. The community I grew up in simply wasn’t capable of holding me in it any longer, and being angry about that or trying to change it wasn’t productive for my own well-being.

I’ve had to accept the rifts caused in the wake of Mormonism’s inability to acknowledge my experience. I had to learn how to accept that my old community viewed the void in the church left by people like me as acceptable collateral damage. I had to learn that it wasn’t my duty to convince them to find the moral courage to stand up in the face of the wrong that was being done in the name of God by their own leaders. In short, I had to choose to go my own way.

Being forcibly pushed out of the structure Mormonism provides is no cake-walk. But I must admit that, again in hindsight, it is probably the best thing that ever happened to me. I wonder if I would have ever faced the abyss of the magnificent unknown if my world hadn’t collapsed around me. It was the start of a really beautiful life that continues to surprise and delight me. One of those surprises is that there is nothing I can ever do to sever completely my tie to my Mormon heritage. It is part of my being. And this is why I write today.

I wanted to highlight some of the parts of the Josh Weed’s blog post that hit home for me. I’ll add some of my own commentary along the way. I also encourage my LDS friends and family to read it themselves with an open heart, seeking understanding.

“You see, LGBTQ people aren’t ‘the world’—we aren’t outsiders that the Mormon Church needs to protect itself from. We are you.”

Josh and his wife are both therapists, and so with the rise of their name recognition within Mormonism, they had lots of experience with the LDS LGBT population. When I first came out, I started to blog about my experience and my inbox was soon inundated from emails from LDS LGBT people from all over the world pouring out their pain and asking for advice and help. It was overwhelming for me. I had thought that I was the only one.

“They would come and sit down with me, and they would tell me their stories. These were good people, former pastors, youth leaders, relief society presidents, missionaries, bishops, Elder’s Quorum presidents, and they were . . . there’s no other way to say this. They were dying. They were dying before my eyes. This is what the church’s current stance does to LGBTQIA people. It actually kills them.”

They were dying. I saw this so clearly in my own outreach. I had experienced it myself and survived it. But to read those emails pouring in from people around the world who had no one else to reach out to speak about the depths of their pain was too much. How could the church, MY church, do this? How could good people not see the evil being done right in front of their eyes while they echoed “amen?” This cut me.

As I’ve grown in my understanding, I’ve developed language for expressing what it is like to grow up gay in the Mormon church. It has allowed me to speak about that experience in increasingly better terms and which demonstrate why the claim that “the church’s current stance…actually kills them” is not simply an exaggeration.

Did you know that an infant left untouched will die, even if all its other needs are provided for? In Romania, orphanages were severely overcrowded after the fall of communism. The result was that, except for providing basic needs- limited staff could not nurture, hold, and provide loving touch for the children. Otherwise healthy kids died in the absence of that nurturing. There is an innate need we have a the core of our being that absolutely needs that sort of human attachment.

I think intimacy is a vital form of human expression. It is the only way by which we can express certain layers of our being. When a person is not allowed express that or receive that, those parts of them calcify. If neglected to too long, that calcification spreads. Reading Josh Weed’s words brought back a flood of memories and, for the first time, I realized that I knew what it felt like to be slowly calcified inside.

Starting in high school, I began to flinch when people would touch me. It became more pronounced in college where a friend actually confronted me about it. “Why do you flinch whenever someone touches you!?” It wasn’t something I controlled. My body just pulled away instinctually. I was calcifying. As the years passed I felt more and more empty and isolated from my own being. I was dying. It got to the point where the only thing that I found comfort in was imagining how I could end my life in vivid detail. This is what “being faithful” looks like for an LGBT person.

Lolly, Josh’s wife said this:

“If it were just about sex, we could handle it. We would be willing, and were willing, to sacrifice that. People can live without sex. [I asked my mom] what it would be like if she had to marry her best female friend, Joyce, whom she loves dearly. I asked if it would be as fulfilling as her love for my dad because she also loves Joyce. She said, ‘No, it would be different because I don’t love Joyce in that way.’ To which I said, ‘But you do love her and you could live a nice life. But, would it compare to your life with Dad?’ She said ‘no.’ Then I asked if the difference in a life with Joyce and a life with Dad was just about sexuality. Would the only difference in a relationship with Dad and a relationship with Joyce be between having sex with a man versus having sex with a woman? The answer was clearly no. That is because she is not romantically attached to her best friend. And that is what human beings need to be healthy. All of us. Romantic attachment.”

I have to be honest about the toll my faith in Mormonism took on me. Trying to build a sense of self-worth after at least 15 years of receiving messages and feeling, very acutely, that there was something vile and ugly about me that I apparently had no ability to get rid of is not a simple task. Especially having to build that alone, with no model or structure, without the support of a community… and even in the face of it’s opposition. I am still healing. I’m still working on decalcifying those parts of me that I locked away- almost 8 years later.

I don’t share that so that you feel sorry for me. As I said, I can only be grateful now for the life I’ve grown into. I share it because I think it is important for my LDS friends and family to fully understand the impact the church has on the lives of LGBT people. Just consider how much energy and time and life is wasted in efforts to deny or fix sexual orientation and of all the time and energy later spent to heal the trauma of that experience! Think of the lives we literally lose to that unnecessary suffering!

Utah, the place where Mormon culture permeates the population most fully, leads the country in teen suicide- and it is growing at alarming rates. Last year, there were 44. That represents about 3,000 years of human life- gone. I’m not implying that they were all LGBT. But LGBT kids are at much higher risk for suicide, homelessness, and marginalization than their peers, and I simply want to draw attention to the fact that, suicide or not- the years wasted to unnecessary suffering add up. It’s a lot of human potential to regard as an acceptable level of collateral damage. It’s hard to understand how any decent person could shrug shoulders at that.

For so many years, all I could see about my orientation was that it was vile. Like Josh, it never even occurred to me that it could be something beautiful. I came out simply because I knew that if I kept it locked up much longer, I would die… not because I had any level of confidence that embracing my orientation would produce better results.

“How could an aberration be beautiful?”

“Blue eyes, he pointed out, were an aberration form the norm. Dark eyes were the biological default in humans, and blue eyes were an aberration, a genetic defect even. Yet some consider them to be very beautiful. Then he moved on to the second example. ‘Josh, there’s beauty in variation. So much of what we find beautiful is variation! Like, look at the Grand Canyon. People travel for thousands and thousands of miles to see the Grand Canyon and its majestic beauty. And what makes it so beautiful? It’s an aberration. It is a variation of the norm. And we love it.’”

This is what I hope Mormons would understand: By not embracing us… by putting borders around how much of ourselves we are allowed to be, the Church’s position on LGBT issues makes it so that we cannot embrace ourselves. And if we are to ever love ourselves and be able to see God in us, we are forced to leave. Not only does this make the Church less vibrant, it blows out the light in too many beautiful souls for far too long. It is a sin.

LGBT people in the church have been at the receiving end of all kinds of vile attacks by LDS leadership, however well intentioned they are. It’s past time it sees the beam in its own eye and wake up to the indisputable fact that all is seriously NOT well in Zion. The recent decision to boot Uchdorft out of the 1st Presidency (something that has rarely happened in the history of the modern church) should make Mormons uncomfortable. It seems to highlight the reality that change will not be coming from the top. Its up to you who are left in the pews to revitalize the church and create the change I have to believe you know is right in your heart.

We are you.

Powerful Jonathan. Thanks for taking the time to write this.

Thanks Jonathan, that was beautifully stated.

Excellent! And I agree with you. The change won’t come from the top.

Thank you Jonathan. I am determined to bring about change.

Thank you for sharing your experience and reflections.

I am saddened when I continually hear phrases and teachings that ignore your reality.