Since starting The Queens’ Tea in 2012, tea has become a way of life, and increasingly, a philosophy for Michael and me. For those who say that they don’t like tea, we say, “There’s a tea for everyone.” For those who think only of old ladies in white gloves who sip tea from floral teacups we say, “Tea is the original social media.” And for those are on the fence about why we think tea can promote social justice, we say, “Tea is a vessel for a story.” Tea invigorates without inebriating and has been used for centuries across cultures for many purposes. For us, tea creates a connection to the earth and to people.

Many of us grew up in a Mormon culture that declared tea detrimental to health. Nothing could be further from the truth, and it takes some time to unlearn bad information, and relearn correct information. For example, antioxidants and polyphenols burst through green tea. According to the Harvard Medical School, “Tea’s health benefits are largely due to its high content of flavonoids — plant-derived compounds that are antioxidants. Green tea is the best food source of a group called catechins. In test tubes, catechins are more powerful than vitamins C and E in halting oxidative damage to cells and appear to have other disease-fighting properties. Studies have found an association between consuming green tea and a reduced risk for several cancers, including, skin, breast, lung, colon, esophageal, and bladder. Additional benefits for regular consumers of green and black teas include a reduced risk for heart disease. The antioxidants in green, black, and oolong teas can help block the oxidation of LDL (bad) cholesterol, increase HDL (good) cholesterol and improve artery function.” It’s not a stretch co call tea an elixir of health. Tea has been a part of all cultures (including Mormon culture!) for thousands of years.

If you know absolutely nothing about the world’s favorite drink, that’s ok! This post will help you get the basics so you can start exploring in depth the rich history and variety of tea.

What is Tea?

Tea comes from the plant known as Camellia sinensis, a shrub native to Asia.  Today, these plants are grown primarily on huge farms, where soil conditions, humidity, and elevation are all essential components to successful growing. Green, black, white, and oolong teas all come from the species Camellia sinensis, although there are a variety of cultivars, i.e., strains of the species. Once the leaves are harvested, the specific steps used to process the leaves determine the type of tea they will become. Processing steps may vary significantly from country to country, and even region to region and farm to farm. For example, a traditional Chinese method for producing green tea involves baking the leaves briefly in metal pans. (This stops oxidation of the leaf from occurring.) In contrast, the traditional Japanese style for green tea production involves steaming the leaves, rather than baking them, as a means to heat the leaves and prevent them from being oxidized. The baking and the steaming result in substantially different flavor profiles from one another. Part of the fun of tea is exploring the surprising varieties of flavor that result from these alternative methods of preparing the same leaf.

Today, these plants are grown primarily on huge farms, where soil conditions, humidity, and elevation are all essential components to successful growing. Green, black, white, and oolong teas all come from the species Camellia sinensis, although there are a variety of cultivars, i.e., strains of the species. Once the leaves are harvested, the specific steps used to process the leaves determine the type of tea they will become. Processing steps may vary significantly from country to country, and even region to region and farm to farm. For example, a traditional Chinese method for producing green tea involves baking the leaves briefly in metal pans. (This stops oxidation of the leaf from occurring.) In contrast, the traditional Japanese style for green tea production involves steaming the leaves, rather than baking them, as a means to heat the leaves and prevent them from being oxidized. The baking and the steaming result in substantially different flavor profiles from one another. Part of the fun of tea is exploring the surprising varieties of flavor that result from these alternative methods of preparing the same leaf.

How Does a Leaf become Tea?

It all begins on the top of the tea plant with the bud (the freshest growth) and the two leaves next to it. The freshest and most expensive teas use only the bud of the plant, harvested in early spring, and usually picked by hand. It’s a labor-intensive process with a small yield. Most commercial teas are harvested in the spring (first flush), summer (second flush) and fall (third flush) and modern technology and consumer demand requires that tea be harvested and processed with machines. For example, our first day working on a tea farm in Japan, six of us harvested nearly a half-ton of leaves!

After the harvest, the leaves are allowed to wither. This step is where there artistry of tea production begins. Like any specialty craft only experience and practice are the ways to know when the leaves are “done” withering. Talented tea farmers know by sight and smell when it’s time to begin the next step.  The Japanese tea farmer we worked with stayed up all night with the tea leaves, checking in on them hourly to perceive by scent and sight when they were “just right” to move on to the next step of production.

The Japanese tea farmer we worked with stayed up all night with the tea leaves, checking in on them hourly to perceive by scent and sight when they were “just right” to move on to the next step of production.

After withering, the leaves are rolled. The rolling process breaks down the cellular wall of the leaf to expose the enzymes they contain and exposes the leaf to the ambient air, which begins oxidation. Rolling can be done by hand but machines mostly do the rolling today. The length and force of the roll and the oxidation that follows decides the final result in the cup.

Oxidation is an important step that governs the quality of the tea. There are many variations in the oxidation process. For example, some tea leaves are not allowed to oxidize at all. These leaves become white or green tea. In contrast, black teas are fully oxidized. Oolong teas are somewhere in between no oxidation and full oxidation. Think of it like a sliced apple that’s been sitting on the counter for over an hour. You start to notice the edges of the apple changing to a darker color, and the longer it sits out, the darker it gets. Leaf oxidation is the same concept.

After oxidation, the leaves are fired, or dried. Firing stops the oxidation process once the desired level has been reached. The leaves must be heated to a temperature that will destroy the heat-sensitive enzymes that cause oxidation. The firing (or drying-out process) happens in large drying machines that expose the leaves to an average temperature of 194 degrees F for about 20 minutes, although a variety of factors determine how long the firing actually takes. Like the withering stage, firing is also a stage that demands great expertise of the tea maker. The leaves will become moldy if too much moisture remains, but will be flavorless if over dried since the leaves won’t be soluble enough to infuse in hot water. After firing, the leaves retain about 5-6% water.

On the left, a freshly picked tea leaf. In the center the leaf has been rolled and fully oxidized, and on the right, the tea leaf after drying.

After all that, you have a tea leaf!

What are the Different Types of Tea?

The varieties of tea are endless. For now, we will focus on the major categories bought and sold in the west: white, green, black, oolong, pu er, and herbal teas.

Keep in mind that all teas can be scented or flavored. Historically teas have been scented with flowers (in the case of a jasmine green tea) or with smoke. Teas can be flavored with oils like bergamot (a citrus from Italy), which results in Earl Grey tea. Those methods of flavoring are still in use today, although artificial flavoring is also used. Artificial flavors are not the end of the world, but we try to avoid them.

White Tea

There are two main types of white tea. The first is Silver Needles that is made from the downy, fresh bud picked in the early spring that is allowed to wither and dry. This tea infuses a delicate, soft flavor when steeped. Historically, Silver Needles tea was such a luxury good that it was available only to the Emperor, but I’m a working-class peasant and I prefer something more full-bodied. The second variety of white tea is called Pai Mu Tan (sometimes transliterated at Bai Mu Dan). It is a white tea harvested in late spring or early summer. The bud and the two adjacent leaves are plucked. When steeped the leaves infuse a soft yellow-green color and nutty flavor. White teas have become popular for use in cosmetics, which has driven the cost of white teas up around the globe.

Green Tea

Green tea originated in China 4,000 years ago, making it one of the oldest drinks in the world. Buddhist Monks from China who liked the stimulant effects of green tea during meditation introduced green tea and Buddhism to Japan in the eighth century. Today China, Japan and a number of other Asian countries produce green tea and the varieties are nearly infinite. For example, Dragonwell is a yellow-green flat leaf from the Zhejiang Province that infuses a golden pale color and has a touch of bitterness and acidity to the taste.

Gunpowder comes from the same region but the leaf is rolled into very small, shiny pellets that vary in color from pale to dark green. This tea leaf is often blended with mint. Gunpowder is shunned by the Chinese and is sold primarily an export to the west where it is widely consumed.

Japan produces Sencha, Matcha, Genmaicha, Bancha, and Hojicha. (“Cha” is the Japanese word for tea, hence mat-cha, sen-cha, genmai-cha, hoji-cha.) Sencha leaves look like tightly rolled cooked spinach. When steeped in hot water, the liquor becomes pale green and cloudy, with a smooth, slightly oily texture. It has an aroma similar to the sweetness of zucchini and spinach with a slight marine smell and taste. Matcha on the other hand, is a powder. It is made from Tencha leaves but instead of being rolled into a tight needle shape like Sencha, the entire leaf is ground into a fine powder that becomes a beautiful jade color. When brewed, Matcha is an intense dark green color with a muddy texture. Matcha is used in the tea ceremonies and can also be used for cooking.

Bancha translates as “common tea” and is harvested in the fall. The leaves are much more coarse than a Sencha due to the longer growing season.

Milk and sugar are not recommended for green or white teas.

Black Tea

Black teas are among the most widely consumed tea in the west. Black teas have more flavor and pack more of a caffeine punch than do white or green teas, plus most black teas in the west are served with milk or sugar. Black teas maintain their flavor longer and because of this, have historically been used as a trade good. Black teas are produced primarily in China, Sri Lanka and India, although Japan has been experimenting with black tea production on a small scale. Black tea is also produced in Indonesia and Africa.

From China we get black teas like Yunnan, Lapsang Souchong, and Keemun. Yunnan is grown in the Yunnan Province and is among the best black teas in China with many grades. The leaves are brown-black with a number of tawny buds depending on the grade that when brewed create a dark brown color with a taste of light astringency, but no bitterness, and a floral note.

The complete opposite of a Yunnan would be a Lapsang Souchong. The leaves that make Lapsang Souchong are withered over fires fueled by spruce or cedar, which gives the leaves a distinct aroma and taste much like a campfire. The leaves are large with the color of charcoal that when brewed infuse an amber color. The powerful, smoky aroma and flavor is unlike any other tea you’ve ever tried and likely will take some time to get used to. Finally, Keemun (also spelled Qimen) comes from the Anhui Province. These leaves are striking for their simplicity, almost black in color, tightly rolled, short and even, and slightly shiny. They infuse a dark copper color with a rich aroma. Keemun is used as the basis for a number of blends and scented teas. (For example, we use Keemun in our English Breakfast blend.)

Sri Lanka used to be known as Ceylon until 1972, so the teas produced there are still referred to as Ceylon teas. Sri Lanka produces black tea almost exclusively. Ceylon black tea is grown on numerous estates at various altitudes, so often you will see the distinction between “high grown” and “low grown” tea. Generally, Ceylon black tea has a crisp, spicy aroma that infuses a bronze or sometimes mahogany color. This is one of our favorite teas that we drink with a splash of milk.

Black teas from India will rock your world. In the mid-nineteenth century, Assam tea became extremely popular with the British. Assam teas (named after the region in which they are grown) are spicy, astringent, tannic and are able to support the addition of milk and sugar. Assam leaves are mostly used in blends. For example, English Breakfast tea is usually blended with Assam as the base. Most famously, Assam is used as the basis for Masala Chai, a black tea with Indian spices. (Chai translates as “tea” and Masala translates as “spicy.”) Chai spices include cinnamon, cardamom, ginger, black pepper, anise and cloves. Once steeped, sugar and milk are added to create a delicious drink that has become very popular in the west. We purchase our Masala Chai directly from an estate in India and we blend in a bit more ginger.

The Darjeeling region in India produces Darjeeling tea, a black tea with four harvest seasons: spring, summer, monsoon, and autumn. The finest grade Darjeeling teas (spring and summer) can fetch a high price and are exported around the world. The leaves are well formed and depending on the harvest season can be green with silver buds to a dark color. There is nothing better than a Darjeeling tea on a spring morning.

Oolong Tea

Inaccurately referred to as “semi-fermented,” oolong teas are actually semi-oxidized.

China produces oolong teas, but some of the best oolongs come from Taiwan, where the leaves are oxidized from 60% to 70% depending on the region and the tradition. Because of such variation, there are literally hundreds of oolong teas on the market. Some are more floral and some have a more roasted flavor. During rolling the leaves can be crumpled, or more often, they are rolled into a tight twist or a ball. When steeped, the balls unfurl into a huge, beautiful leaf that demands to be admired.

Pu Er

Michael and I first tried Pu Er in a teahouse while we were lost in a hutong in Beijing. At first I did not care for it at all, in fact, I felt like I was somehow drinking my grandma’s musty basement, but over time, I’ve come to love it. Pu Er falls under the category of a Dark Tea and the word “fermentation” does apply. In a sense, Pu Er tea is like wine because the leaves are fermented and aged. The traditional method of production is a compressed green tea, which ferments naturally over a period of years. This process has been in existence in China for over three thousand years. The fermented tea could be compressed into cakes or bricks, which made them easy to transport. (PIC 18) The second method creates “Cooked” or Black Pu Er teas, a process that accelerates the fermentation process artificially. The leaves are a dark, deep brown and smell like mildewed moss. When steeped, the liquor is a dark, almost black color that reminds me of coffee. A Pu Er should age a minimum of five years in a Pu Er cave with strict requirements for temperature, humidity, etc. The oldest Pu Er I’ve tried was 40 years old. I don’t crave this tea every day, but when I do, nothing else will suffice.

Herbal Tea

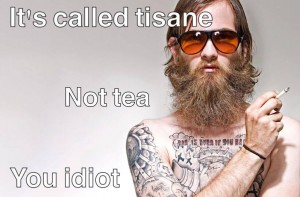

Anything can be steeped in hot water and probably has been since the dawn of time. Plants like rooibios, a woody shrub from South Africa, peppermint, ginger, chamomile etc can all be steeped in hot water. Very technically speaking, any herb steeped in hot water is properly called a tisane, not tea, but nobody speaks like that except really annoying hipsters. Again, technically speaking, anything that does not contain Camilla sinensis is not tea but everyone refers to it as “herbal tea.” When steeped, the Camilla sinensis releases caffeine, but herbs do not.

except really annoying hipsters. Again, technically speaking, anything that does not contain Camilla sinensis is not tea but everyone refers to it as “herbal tea.” When steeped, the Camilla sinensis releases caffeine, but herbs do not.

The canvas for many tisanes (or herbal teas) is rooibos, a woody shrub grown in South Africa. Translated as “red bush” it can be steeped and enjoyed by itself, or is often blended with herbs. For example, we make a blend called The Queen Bee, which is a blend of organic rooibos, organic lemongrass, and organic chamomile (with a few cornflower petals blended in for a pop of blue color). Similar to rooibos is a plant called honeybush. I’ve heard it described as “sweeter” than rooibos, but, personally, I can’t tell the difference. Under the tisane umbrella is Brigham (or Mormon tea) which is really Ephedra viridis, a species of Ephedra indigenous to the Western United States. It’s actually not bad, but it’s not my favorite either. In pioneer journals from the nineteenth century, people wrote that when they served this herbal tea at home they added lots of sugar and milk to cover the bitter taste. When I tried it, I didn’t think the taste was bitter at all, I found it rather pleasant, it’s just not my cup of tea, so to speak.

How to Steep a Perfect Cup of Tea

We often hear people say that they do not like tea, that they find tea bitter to the taste. This is another way of saying that the tea was improperly prepared. Tea leaves are more delicate than a coffee bean and they require just bit more TLC before they will wow you with their flavors and sweetness.

Water temperature is essential. If you’re steeping tea with boiling water, you’re doing it wrong! (People from England will disagree with me on this point, but they are doing what experts call “making a mistake.” I prefer to prepare tea from the methods and traditions of Asia, not Europe.) Boiling water scorches tea leaves, especially the more delicate green and white tea leaves making them bitter and frankly, for me, undrinkable. The way to avoid this is to use water heated just under a boil for greens, blacks, and oolongs, and even a bit cooler for white teas. If the water does reach a boil, give it a few mintues to cool down.

As important to water temperature is the steep time. Tea does not get “stronger” the longer it steeps. A longer steep time makes tea bitter. Steep times come down to preference and we generally prefer tea steeped for 2-3 minutes. As a general rule of thumb, the hotter the water, the less time it needs to steep.

The exception to everything I said above are herbal teas. Boil water and steep for as long as you like because you can’t oversteep an herbal tea.

We haven’t even touched upon the philosophical principles of Cha No Yu (meaning “the way of tea”) or the beautiful Japanese tea ceremonies, or the imperialist history and espionage of Robert Fortune and the British Empire, or the tea history of Mormon pioneers. However, I hope I’ve provided a thorough overview of tea history, tea production, and the wide assortment of teas. Remember, “There’s a tea for everyone!”

Happy Sipping!

Say it whatever you like about teas health benefits and how everyone else around the world sips it, it’s still against the Word of Wisdom for Mormon’s to consume no matter what it’s benefits. Your insights for non-tea drinkers into the world of tea leaves; growing it, the many varieties of it, the brewing, etc. while all very interesting may fall short of converting Mormons to become consumers of it. There are plenty of Non-Mormons that I’m sure enjoy your quality product and I wish you much success in selling to them.

Comment

Commuterdude,

Where in the Word of Wisdom found in Section 89 of the Doctrine and Covenants does it forbid drinking tea? In addition, where does the Lord state in Section 89 that the Word of Wisdom is to be obeyed by way of ¨commandment¨?

Good thing the Word of Wisdom us there to protect Mormons from Green tea while allowing room for energy drinks and diet Coke.

More green tea for this apostate and the rest of the world. Thanks for an interesting and informative article.

I’m Mormon and I regularly throw the Word of Wisdom out the window because I believe it is outdated and irrelevant. Tea is a wonderful thing! I’m also fond of a little wine now and then but I feel like I’m still abiding by staying away from coffee (don’t like it) and hard liquor. It’s just like the Pirates codes, “more like guidelines”.

Interesting comment. I too wonder why the poison of Coke was suggested to replace my afternoon cup of tea, which I use to give me a mild bit of energy and mental clarity to finish my work day. No sugar, no chemicals. I’m very confused at why soda and chocolate, which are just as addictive are even suggested. If we were to advocate for clean eating, unprocessed food, I’d understand that. But we don’t. The fact is a lot of people, Mormon or not, can’t afford to eat all that healthy all the time. Now there’s something to ponder; how do we make that happen.

Seth, I really appreciate your article. I learned a lot from this. Having good information helps people make better decisions, regardless of one’s religiosity.

I once had a stake president who argued in a gospel doctrine class that the Word of Wisdom ban on tea included herbal tea, but I’m pretty sure he just liked the sound of his own voice. No one took him seriously.

I loved this post! Thanks for the great info. I was introduced to tea drinking on my mission. I served in a mission where fresh herbal teas were served to guests regularly. In the beginning I disliked the tea and even though my mission president had given guidelines about what teas we could drink and still be in keeping with the word of wisdom, I always felt guilty. I experienced a lot of cognitive dissonance weighing my mission presidents guidelines against the guidelines I had learned growing up as a Utah Mormon. I struggled to feel like a worthy temple recommend holder while drinking all that tea. Over time I grew to love the teas we were served and gained a nuanced view of the word of wisdom. Upon returning to the states, I continued drinking herbal tea regularly. Because I lived in a strong Mormon culture, I received many a questioning eye from family and friends when I would steep a simple cup of tea. Telling family and friends that I started drinking tea on the mission with permission from the mission president didn't seem to help. I almost felt like I had to drink my tea in secret because even though it was just "herbal tea" it was still TEA and I was not avoiding the "very appearance of evil." I sure wish I would have known the word tisane back then! I could have told them it really wasn't tea at all, just tisane so I was okay! After researching the word of wisdom and considering health benefits, I don't have any problem drinking tisane or tea now. Hopefully this post will help the Mormon culture relax a bit and begin to appreciate tea. If not, at least it will arm returning tea-loving missionaries with a come back to the accusation that tea is tea and it's more important to avoid the appearance of evil. I can't wait to try a cup of The Queen's Tea next time I'm in Utah!

Ree thanks for your comment about your experience with tea. Do you know if Matcha fits the bill or if it is still from the “Green Tea” plant and so it is not “sanctioned”. As with everything it is important to go by the Spirit of the Law instead of the Letter of the Law. If you don’t have any experience with that then just comment on that. My wife and I enjoy a good berry chamomile tea on a winter day or with a sore through. I’m just looking for a better alternative to drinking Coke-Zero or other caffeine supplements.

Pork cuts for Jews coming up next?

The tea part of the word of wisdom never made sense to me until few months ago when I finally did a research and discovered the word “tisane”.

I remember being taught by the missionaries 20 yrs ago and they specifically mentioned “no black tea”.

Somebody in Sunday school said that green tea is also included in the no-no list.

For me it is a bit hard to know what tea to drink/not drink. I love green tea and I don’t think it’s agains the WoW.

I live in England now and have come across wonderful teas. I’ve also seen English breakfast tea at members homes. So yeah. I’m still confused.

I dislike the guilty feeling whenever I drink a delicious cup tea. I recently has jasmine infused orange pekoe and it’s the most delicious tea I’ve ever had but yet here I am thinking how many stars in heaven I might be missing.

What frustrates me about the WoW is that most members ignore the list of advice. Here I am avoiding meat sparingly but am concerned about my occasional tea drinking, but yet some members drink soda all day long with junk food but don’t ever drink tea or tisanes.

Since the WoW is also a physical law, who is really taking a better care of her body at the end of the day?

Hey Orange Pekoe, I like your comment. I am an active, temple recommend holding, member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints. I completely agree that it seems silly that so many people hold strictly to “what types of tea are allowed” and “what are not allowed” and then debauch themselves on candy, soda, meat, etc. etc. The thing is, just because someone makes mistakes in one field, does not mean they are not trying in another. Just because we sin, does not mean that we are not making an effort to be better. It can be an easy thing to miss, and I know that I judge people for it all the time, by accident. But let us let others take their time learning to become better, as we would hope they would let us. for now, I commend you on your insight into controlling your consumption in many areas and putting in sincere effort. Let’s hope everyone else follows suit, and that I can stick to my own New Years resolution for cutting back on candy 😉

Love this

Your information is amazing. it is going to take some time to absorb it all. Well done. I am a 60 yr old RS woman and interpret the tea thing to be as those that contain caffeine. I do believe the Lord put plants/herbs on the earth to nourish our bodies. I would like to open a tea shop in my little town in central UT. So I will study this more in depth. Thanks again. Are the Queen’s Teas your brand? If so I would like to know about them.

I’m so confused…but I loved your article. I am going to Japan this month and while I want to immerse myself in the Japanese ways while I am there, I am also worried about drinking tea (Word of Wisdom). Is it wrong of me to say I’ll drink it “if it’s a necessity” and then ask forgiveness later? ha ha!

Hi Mari, I guess this is a little late, but I have been to Japan and never found myself in a situation where it was rude to decline the wrong types. You should be fine, and people may even ask why, which is an amazing opportunity to share, and examine if you truly understand why you are obeying the word of wisdom.

OH no! Because Mormons eat candy it must be OK to throw the Word of Wisdom out the window. I decided it was “outdated” and I drink wine, but I keep the Word of Wisdom. Is everyone on here deluded?