What I Learned From Fighting

When I was a kindergartner, there was a tough kid in my class named Tavaris. We had beef. My family knew about Tavaris and often times the teachers did enough to keep us from verbally and physically accosting each other. My mom hated fighting, but she was not opposed to clapbacks. One day things got particularly bad after school. Tavaris brought his third grade big brother. This was not the first time we scrapped, but this time he was extra ruthless. They proceeded to wail on me with their backpacks for a bit before my mom and eighth grade big sister rolled up in our Ford Aerostar. They pulled the bigger kids off me, and my sister got a couple of good hits in before they ran off. That was the last time Tavaris and I fought.

This is how five year old me learned conflict. Running away, taking deep breaths, tattling to authority, turning the other cheek, and even talking with those who would otherwise hurt me often saved me from harm. But when these things do not solve your problem, you are left with one option: fight.

I later learned that, when it comes to fighting, there are different ways third parties can participate. One can step in to either break it up or throw blows of their own. Then there are those on the sidelines who shout words of encouragement or whip out their phones like “WORLDSTAAAAAR”. Some see the conflict and simply walk away, afraid that getting involved might lead to harm. My least favorite participants are those who watch, only to offer consolation after the fact. They talk about what a jerk that guy is and offer other generic words of consolation. When this happens to me, all I can think is “Why did you let that happen to me then? We could’ve taken him! Where were you?” I was never bold enough to ask this question directly, but I imagine the answer would be something like “Well, I didn’t want to get hurt,” “It’s not my fight,” or perhaps, “I thought someone else would.” The coward in me understands, but the humanist in me is livid. How can we be so insensitive to the injustices happening to people around us?

Here is how I gauge whether or not it is acceptable to stay out of a conflict: if what is happening to someone else is more reprehensible than what could happen to you and that individual by intervening, you are morally obligated to act.

With that, let me again bring up what is happening currently with the LDS church and homosexuals. In a previous post, I quoted scripture, academia, and our leaders to challenge the notions that a. the scriptures condemn homosexuality as we presently understand it and b. we have to take the brethren at their word about homosexuality. Here, my object is to show that inaction regarding these policies is more harmful than action.

Weak Allies

I have taken to forums to see if I could find anyone else with the likeminded desire for change in church policies. I found several. Like me, they perceive the policy as an injustice. However, I am troubled that people agree that these policies are unjust, but when presented with the idea of fighting the policy, almost nobody wants to act. The excuses are predictable: “Fighting won’t change anything” says one. “I don’t want to get excommunicated,” says another. “It’s easier to just walk away if you don’t agree,” “It’s better to just comfort those affected by the policy,” “I don’t want to be ostracized by my family and friends.” The list goes on. I will not say I do not understand these concerns, but the source of these concerns is the same: selfishness.

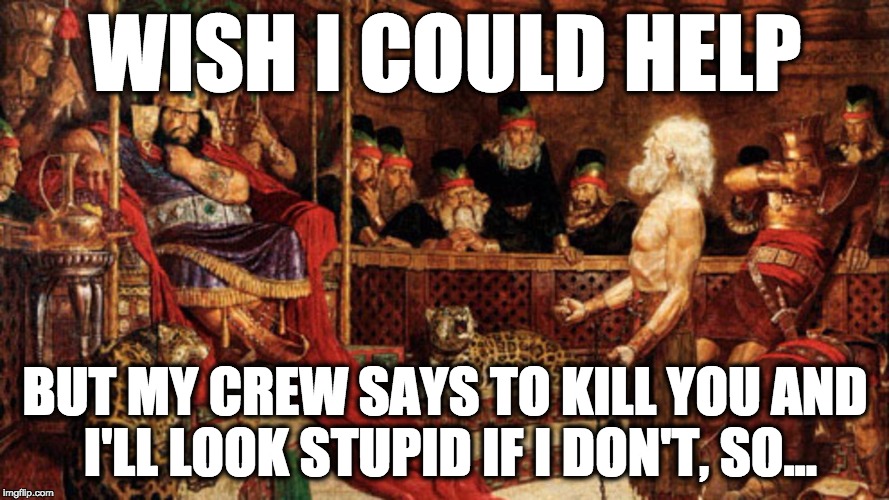

There are LGBTQ Mormons out there who are dispossessed, depressed, and killing themselves as a result of the academically, scripturally, and morally disputable policies affecting them. Yet, because we fear the comparatively small consequences that MIGHT ensue for doing something about it, we are willing to let people suffer and even die. Real talk, brothers and sisters, we have to do better. We have covenanted to do better. King Noah and Herod Antipas – these men let prophets die to save face! Are we not better than them?

No More Excuses

If you are afraid you will not make a difference, consider this: Book of Mormon prophet Abinadi had no earthly authority and converted one soul during his mission, but that one convert baptized many and would later beget one of the greatest prophets in Book of Mormon history. Also remember, Rosa Parks wasn’t a leader or even the first black woman to refuse giving up her seat on a segregated bus, yet she was a catalyst.

More importantly, the marginalized do not forget how the privileged and empowered behave with regard to them. This is how things like 9/11, the conflict in Iraq, and Florence and Normandie happen. These things will likely continue to happen because on the other side of the coin, those with privilege tend to be very forgetful. These are they who called Baltimore and Ferguson protesters animals and terrorists; they who ask why there’s no white history month or W.E.T.; they who asked “why would anyone do this to us” after 9/11 and the Paris attacks; and they who thought invading Iraq was a good idea. They with privilege and minimal recollection of their history have brought upon this country, this world, and this church too much trouble with their apathy toward the marginalized and selective memory of the past. They cannot have the high ground again. If we can’t remember those who don’t share our privilege and help bear their burdens, it will haunt us in the future and the damage will take years to undo. Your effort to use your privilege to give the marginalized a voice matters, no matter how small.

If you are afraid of excommunication, you may be missing the mark. I am sure many of you would lay down your lives for those you love, for those you call brother and sister. If you would not lay down your church membership to save a life, there is a problem.

If you feel things will just get worse, I will admit that is very probable. Things typically get worse before they get better, especially when it comes to people. People do not seem to like change; our brains are designed to create and maintain efficiency with habits, routines, and traditions. The brain adamantly resists any attempts to change these, so expecting resistance is wise. Pushing through this process, however, can deliver an addict from dependence or a people from oppression. That hope makes the struggle worth it.

If you are inclined to walk away, reconsider. We need your strength. I do not know your mind and I do not know the depth of your conversion. Consequently, I may not have the right to ask that of you, but if your conversion goes beyond that of the people and the church as an organization, your stance on church policy should not be enough to overshadow your testimony of the restored gospel. For the sake of those who would accept the gospel, please stay. They will need you.

If you are concerned you will lose friends and the love of your family, you should reconsider the value of those relationships. Being lonely sucks, but you are being dishonest with yourself and with those you call family and friends. Frederick Douglass once said “I prefer to be true to myself even at the hazard of incurring the ridicule of others rather than to be false, and to incur my own abhorrence.” You cannot find happiness lying to others about who you are. That lie is certainly not worth your own abhorrence, let alone the lives of those you call brother and sister.

If you are of the opinion that mourning with those that mourn and comforting those that stand in need of comfort is adequate, I would like you to remember what my big sister did for me when I was in distress. When people bigger than me were hurting me, she did not stand by with baked goods and funeral potatoes to comfort me after I got hurt. She got in there and knocked some heads. If we would call ourselves allies, we must be more than just a shoulder to cry on.

If you feel we are asking too much too soon, I want you to consider this month (Black History Month) a couple of things about our nation’s history: In August of 1963, the same month as the march on Washington, Newsweek asked white folks what they thought about it. Nearly 70% of them thought Dr. King and those following him were asking too much. In 1962, Gallup asked white folks if they felt black kids were receiving equal educational opportunities. Ninety percent said yes. In the 1850s the word “Drapetomania” was coined by R. Samuel Cartwright to describe the mental condition of slaves who wanted to run away. Let that sink in. Wanting to be free of slavery was considered a mental illness. Every time in America’s history when the privileged thought things were fine, but the marginalized did not, guess who was right. Historically and statistically speaking, if you were to tell me that I am asking too much too soon, I should not believe you. Therefore, I will not feel guilt in agitation. I understand that there is an order in God’s kingdom, but there must also be justice. Order is not a victory without justice.

All this said, brothers and sisters, I must be clear that though I am proposing challenging a church instituted policy/revelation, we must aim to be civil in all our communication and action. When Nephi broke his bow, Lehi lost it for a moment and murmured against God. Nephi made a conscious decision to not complain and take initiative. After he did that which was in his power to do, he returned to his father and gave him another opportunity to operate in his prophetic calling. Though we also read that serious words were exchanged (2 Ne 16:24), it seems clear that he still respected the office and sustained the Prophet. We should endeavor to do the same.

Conclusion

At BYU, I had a choir teacher tell me and the rest of the singers that we were all there because we had talent. She then told us that for the rest of our lives, so long as we had our voices and were able, we have an obligation to sing in our ward choir. This talent we were given is how we glorify God and sustain our choir leaders. I felt she was right and would later learn that this a covenant all card-carrying Latter-day Saints take upon them – to use all that the Lord gives us, including our talents, to build God’s kingdom.

Brothers and sisters – you with voices, knowledge, influence, and with every other privilege, gift, and asset – you have a moral obligation to challenge the status quo. This is not the time to turn the other cheek, but to “bear one another’s burdens that they may be light” (Mosiah 18:8). Our LGBTQ brothers and sisters are outgunned and there are not enough of us coming to their aid. We will one day render an accounting of what we did with our gifts and inaction will condemn us. So speak where you will be heard, write where your words will be read, teach those who will learn, and lead those who will follow. It’s time, as Black Lives Matter leader Brittany Packnett put it, to move from being just allies to accomplices.

I applaud your call to action, Brother Jones. I sat on the sidelines once, morally mute, paralyzed by fear, while others spoke out against the prohibition against my Black brethren having the priesthood. I have found a way to work for change within the Church: becoming a conscientious objector. The Church-owned Deseret News recently endorsed conscientious objection as an acceptable tactic against morally unacceptable practices and policies. That should apply to morally unacceptable practices within the Church like "The Policy." I describe how to become a conscientious objector on my blog mormongrail.com I think I can make more of a difference as a member in good standing who finds ways to object to uninspired practices.

I've been speaking out as best I can. I am definitely the "odd one out" at church; especially in the eyes of leadership. Thanks for the encouraging post.

James, my situation is somewhat different from yours – I'm an inactive non-believer, though still "attached" to the church through active believing family members.

Although you and I are alike in our distaste for "the policy", my distaste for LDS practices and policies apart from the one policy likely is far wider (and possibly deeper) than yours. As a result, my voice does not count for much in LDS circles, and I'm not likely to be present in person to fight for anyone who is being mistreated at church.

I've already told the one church official that may count (my Stake Pres) that I am opposed to the policy, that I have made my opposition known on Facebook and other online locations, and that I see no reason not to continue to do so. I've let him know that I'll respond if he thinks that I'm a candidate for discipline. The only lever that my views may pull at this point is that I believe my SP thinks he might be able to get me back to activity, though I've told him that that is extremely unlikely.

What would you suggest as possibly helpful actions for someone like me. You see, my inactivity and disaffection may make it easier for active believers to dismiss concerns about the policy as the rantings of apostates, and I'm worried that this may result in an overall negative contribution from me.

There are two poles in the understanding of Mormon ecclesiology. Each attracts its adherents. One I call Deistic Mormonism, wherein God initiated (in some fashion) the Restoration but then left it, in large measure, for mortals to perpetuate. In this telling, institutional structures, social networks, rational calculation, and personal biases and predilections best account for understanding the maintenance of the Church, its selection of leaders and development of its doctrines/policies. The church is, in essence, “managed” following secular Organizational Behavior models. In a recent post to this website, one would hardly gather that God has much input in callings. Rather, a stake president “took a risk” in calling the future Pres. Monson as a bishop; likewise, “we” need to expand “our” criteria in order to obtain more effective bishops. It’s apparently up to “us”.

At this pole, the “Spirit” may in some sense be present with the Church, but it is pretty vague how and when it operates; it’s more like background radiation. Those at or moving towards Deistic Mormonism are more apt to be continually at sixes and sevens with the Church leadership – something/someone is always wrong, not to their liking. And, as the Church is another mortal power structure, the model for its change is to be found in interest group politics, where aggrieved members combine and agitate for reform; the more agitation, the more likely chastened leaders will see, or be compelled to see, the error of their ways.

In the current situation with the Church’s policies on same-sex marriage and the children associated with it (usually the two policies are combined, but sometimes not), the premise of the critics, stated or implicit, is that both are “obviously” wrong, even immoral, to any clear-thinking, socially progressive member, and obviously wrong as well to God, who is 100% opposed to (if not aghast at) both policies but isn’t being heard by the stone-deaf general authorities. It’s up to the activism of clearer thinking, determined members to set things right.

The other pole – orthodoxy, traditional Mormonism – understands that God instructed that stake president to call “Tommy Monson” as bishop; the stake president wasn’t “taking a chance” on anything. If God wanted someone else, that’s to whom the stake president would have issued the call. God has a will in these matters, is able to make it known and does make it known. It is God at the helm, not a self-perpetuating elite.

Here is Pres. Joseph F. Smith on the matter:

“It has not been by the wisdom of man that this people have been directed in their course until the present; it has been by the wisdom of Him who is above man and whose knowledge is greater than that of man, and whose power is above the power of man. . . . The hand of the Lord may not be visible to all. There may be many who cannot discern the workings of God’s will in the progress and development of this great latter-day work, but there are those who see in every hour and in every moment of the existence of the Church, from its beginning until now, the overruling, almighty hand of Him who sent His Only Begotten Son to the world to become a sacrifice for the sin of the world.” (In Conference Report, Apr. 1904, p. 2.)

And Harold B. Lee:

“You may not like what comes from the authority of the Church. It may contradict your political views. It may contradict your social views. It may interfere with some of your social life. But if you listen to these things, as if from the mouth of the Lord Himself, with patience and faith, the promise is that ‘the gates of hell shall not prevail against you; yea, and the Lord God will disperse the powers of darkness from before you, and cause the heavens to shake for your good, and his name’s glory’” (D&C 21:6 and Teachings of the Prophets, 2000, p. 84-85)

And here most recently is Pres. Nelson:

“The First Presidency and Quorum of the Twelve Apostles counsel together and share all the Lord has directed us to understand and to feel, individually and collectively. And then, we watch the Lord move upon the President of the Church to proclaim the Lord’s will. This prophetic process was followed in 2012 with the change in minimum age for missionaries and again with the recent additions to the Church’s handbook, consequent to the legalization of same-sex marriage in some countries. Filled with compassion for all, and especially for the children, we wrestled at length to understand the Lord’s will in this matter. Ever mindful of God’s plan of salvation and of His hope for eternal life for each of His children, we considered countless permutations and combinations of possible scenarios that could arise. We met repeatedly in the temple in fasting and prayer and sought further direction and inspiration. And then, when the Lord inspired His prophet, President Thomas S. Monson, to declare the mind of the Lord and the will of the Lord, each of us during that sacred moment felt a spiritual confirmation. It was our privilege as Apostles to sustain what had been revealed to President Monson. Revelation from the Lord to His servants is a sacred process.” (“Becoming True Millennials” Worldwide Devotional, Jan 2016)

In the current situation with the Church’s policies on same-sex marriage and the children associated with it, we understand from this perspective that we all have strengths to offer and different burdens to bear, and so we help each other bear them in the context of the restored Gospel; the Atonement of Jesus Christ compensates for all deprivation and loss for those who turn to Him and live as He asks them to live.

Needless to say, there is tension between these two poles. But if what Pres. Nelson related is true, where is the mandate for “righteous’ rebellion?

To the degree that the Church continues to separate itself from 21st Century social norms, to that degree there will be tension within and without the Church and, eventually, persecution. The 21st Century has its strengths – and its weaknesses as well – but it is no more a reliable template for the Restored Church or the Eternities than was Victorian Britain, medieval Europe, or ancient Egypt. The Kingdom of God is not an extension of either the Democratic or Republican platform. “Every plant,” said Jesus, “which my heavenly Father hath not planted, shall be rooted up” (Matt 15:13. This is a fair one-sentence summary as well of D&C 132.)

The Church is not being led astray, neither is it in apostasy. It’s not simply the case that “the prophet won’t lead us astray”; rather, it is that God won’t let the prophet lead us astray. This is the Church of Jesus Christ. I trust Him to lead the church; mortal hands will not pull it away from Him. We should do nothing and say nothing that would cause another to give pause over accepting the first principles and ordinances of the Gospel and being baptized into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Based on my observation, parents who habitually badmouth Church leaders should not be surprised when their children fall away. I say, stay on the Old Ship Zion. Unlike the Titanic, it cannot sink.

Finally, there is also a living being named Satan who impacts behavior and influences action everywhere on this planet. He “stirreth up hearts” to anger and contention and disbelief. His fruits ought to be apparent, but Satan is an inconvenience – really, an embarrassment – to modern, sophisticated liberal thinking, which holds that the locus of evil is located in social and political structures. The devil is thus dismissed as, at best, a metaphor, without “real” influence. It is important to realize that Satan wants members to leave the Church and world to find it contemptible, and he actively agitates for that. Each of us, as well as the Church, has an active, personal enemy.

Comment

Tim Bone,

Thank you for sharing your thoughts, Tim.

I also agree that God will not let the Prophet lead us astray, but I think we differ on how we believe that promise works. I believe that promise requires activity on our part.

Brigham Young said, ““…if God should suffer Joseph Smith to lead the people astray, it would be because they ought to be led astray. …it would be because they deserved it…” He continued, “…if we should get out of the way and lead this people to destruction, what a pity it would be! How can you know whether we lead you correctly or not? Can you know by any other power than that of the Holy Ghost? I have uniformly exhorted the people to obtain this living witness each for themselves; then no man on earth can lead them astray.”

Also, don’t forget the things God allowed George Q. Cannon, Mark E. Petersen, and Bruce R. McConkie to say regarding the Negro. Nearly 40 years later and I’m still dealing correcting people.

In order for us to not be led astray, we must seek personal witnesses of that which comes from the top. Both modern and ancient prophets taught us that. I and many others have not received personal revelation concerning the veracity of the policies affecting homosexuals, therefore, we must act accordingly.

The ways different people can participate is entirely up to them. I don't know your strengths and your talents so you would better know how you're best used than I. I can't lead nor can I speak, but I can write, so I write.

Wherever your circle of influence is, start there, and play to your strengths. There are a lot of forums and facebook groups that may help you brainstorm. I've yet to find one that I feel suits me, but maybe you can.

Comment

Malcolm McLean,

It doesn’t make sense to me that those within the church wouldn’t hear you out over the church’s policy change. At the heart of the matter is justice and you don’t have to be a member of the church to feel empathy for those marginalized within it. Logically, dismissing opinion just because of its sources is flawed.

That said, I understand where you’re coming from. I wish I had an answer for people’s pettiness that allowed you to contribute in a way they deem respectable, but that hasn’t often worked in history over matters of social significance. The revolutionary war, the civil war, the civil rights movement – these events involved angry people fed up with oppression. I suggest you find more of those people whose methods are above reproach and take cues from them.

Thank you for this post. This is where I’m at and, while I don’t doubt I’m in the right place, it’s reassuring to read similar stances. One point that spoke to me, was covenanting to use what we’ve been given for the greater good. No excuses to not move forward. Thank you.