As my dad drove me home from some activity or other when I was a teenager, I asked him a question that had been weighing on my mind: “can Mormons be Democrats?” I didn’t really follow the news very carefully and I certainly didn’t follow politics. On this car ride, though, I was honestly curious. I went to church all the time, I grew up in Utah in the 90s, and I remember being very upset in 5th grade that my Presidential fitness certificate was signed by President Clinton. I mean c’mon, it was President Clinton. Repulsive to my 5th grade sensibilities. So it didn’t make sense to me that any Mormon could possibly be a Democrat.

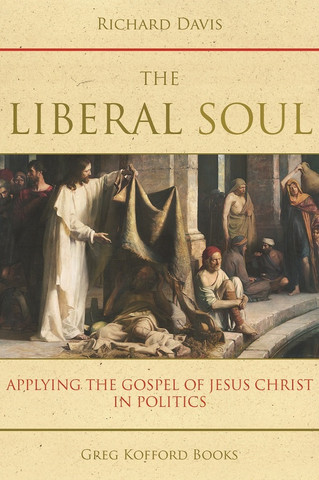

This question, and millions of other iterations of it asked by children and adults across the Church, make up the key problem that Richard Davis’s The Liberal Soul seeks to address: many Mormons don’t believe that you can be Mormon and liberal. This is, in part, because the vast majority of the time politics are brought up in Church or incorporated into a lesson, those politics fall on the right side of the American political spectrum. Many conservatives are vocal about their political beliefs at church, thinking they are talking religion when in fact they are talking politics.

As Davis puts it:

[T]he discussion has become increasing unbalanced in recent years about the relationship between the gospel of Jesus Christ and the role of government in a society. In essence, only one side has really been represented in LDS culture. Books, articles, speeches, and conferences tout the economic conservative and even libertarian approach to government and seek to convince Latter-day Saints that is the ’true’ way.

Davis’s book is an attempt to bring a bit of balance to the Force, but he goes out of his way to make clear that conservative politics are not the Dark Side: [This book] does not claim a monopoly. No effort is made to write out of the Church those who hold differing views” (xxvi). A moderate move considering the regular scathing attacks on Mormon liberals by our fellow Mormons.

Davis explores a number of issues through of a politically liberal and doctrinally Mormon lens: government as ordained by God, equality, poverty reduction, church/state, environment, war, and the need for unity. These chapters can provide a breath of fresh air anyone actively on the lookout for proof that political liberals are welcome as liberals in the community of the Church.

The key frame Davis employs to explore these issues is “the liberal soul,” which is “someone who considers the importance of the individual, the society, and government simultaneously rather than as separate, and typically conflicting, entities. The liberal soul views them as intertwined” (xxi). Practically speaking, this means that Davis advocates for a political orientation that values a combination of personal responsibility, group service, and systemic interventions. Rather than relying alone on individual donations, or on church charity, for example, Davis argues for the consideration of governmental welfare programs. Davis argues that ignoring any one of these three levels of responsibility misses out on important opportunities to serve our brothers and sisters here on earth.

His model is an incredibly moderate one—he doesn’t suggest that government has all the answers, nor does he expect individuals and groups to make everything better by themselves. In case after case he shows how the Church’s own history and teachings align with the “liberal soul” model.

The book is full of smart insights that made me fist pump in the air, such as “A society that wishes to take care of its children does not rely solely on the good will of those who have a desire to hurt those children. . . . Care for the poor and needy is the same” (70). and “Redistribution of wealth is not inherently evil. In fact, the initial distribution of wealth is often simply arbitrary (35).

Davis’s book makes a strong case for how the key problem he addresses can be dealt with on the individual and small group level in the Church. Davis gives advice for liberals to comment in class and respectfully bring up opposing viewpoints (individual), and the book itself is meant as an invitation on the ward and stake level to help broaden perspectives of the political breadth of Mormon doctrine (the small group).

My biggest question after finishing this book is whether there are systemic changes that can address the problem of liberals being and feeling ostracized in their own LDS Church communities. In other words, what is the parallel of the “societal” level of good-doing in an LDS Church context? Not to solve it in one fell swoop or all by itself, of course, but using Davis’s tripartite mixed model of good-doing, what can the Church do to help? Or, is the Church as an institution powerless in the face of anti-liberal bias in its pews?

My husband got me this book for Christmas and I’m so excited to read it. Thanks for the review, Jeff.

Perhaps not many of you remember that Utah used to be a solidly Democrat state in the 60s. Wasn't Cal Rampton a Democrat? (and Carl Rove his aide?)

(BTW, JFTR, IMO Rampton was somewhat respectable. Rove, of course, is one of the most evil and deluded men on the planet. Along with the rest of the Republican Party. So, with regard to the topic of the post, is it about 'conservative' versus 'liberal' "values", or about the survival of the human race?)

The Liberal Soul is an excellent, informative read, and I have passed it along or recommended it to liberal LDS friends of mine. It didn't turn me into a liberal, but it reconfirmed my commitment to never presume to tell anybody which party they must belong to (or not belong to) in order to be LDS.